Hanging Out with a Purpose: Diving into Bandung’s Underground Music Scene

Nongkrong can be literally translated as “squatting by the side of the road with a cigarette” or “sitting around because you’re not doing any work”. It is where the underground music scene in Bandung begins.

"Nongkrong isn’t leisure. It’s the work of keeping culture alive."

PART 1

Getting Your Foot in the Door

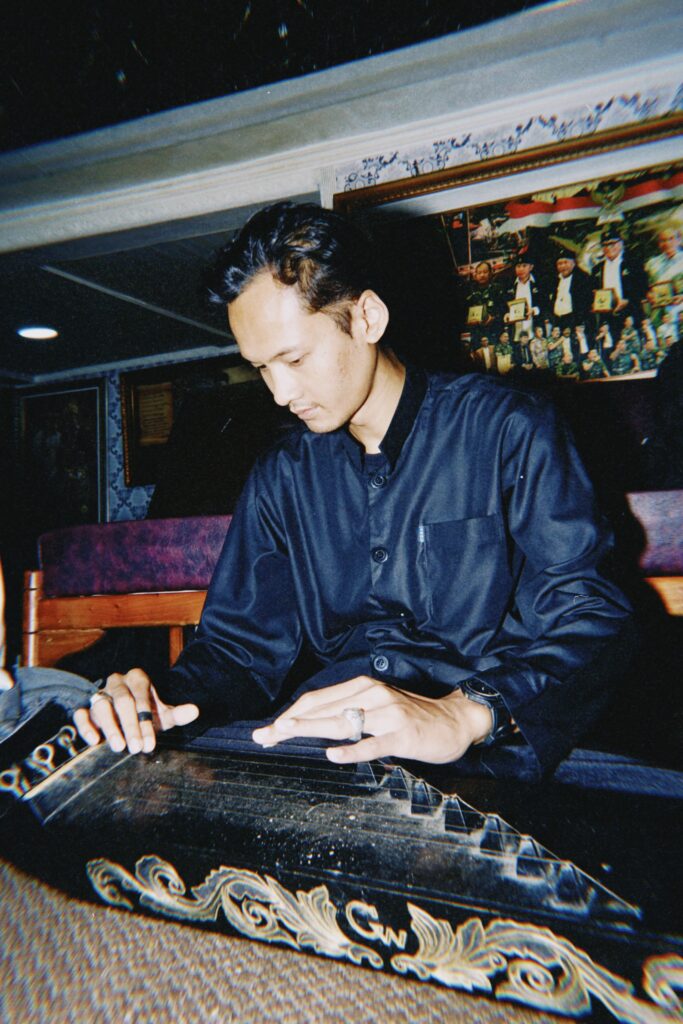

You enter a room as the smell of clove cigarettes and takeaway food leads the way. A step closer. Even before passing the threshold, the sound of laughter and stories reaches your ears. These people are having fun. A step in. “There you go! Apa kabar dong? Kumaha damang? How are you?”. Groups of friends are here and there at the same time scattered and pushed against each other in clusters around the room. Music is playing in the background constantly, sometimes blaring out of a Bluetooth speaker, sometimes produced by someone with their acoustic guitar. This ‘amoeba-like’ assemblage of people thrives around a constellation of objects: overflowing ashtrays, coffee cups, fried snacks and all sorts of sweets and beverages. Remarkably, everyone occupies space in different arrangements, sitting in the lotus position holding on their feet, laying on the ground on the side, sitting on the sofa; humans converging towards the center of the conversation in various configurations. We’ll probably be here until the morning. Someone will leave, someone will stay and sleep to resume conversations and music and cigarettes and coffee as soon as eyes open again. It feels like being in a spiral of sociality, a deep hangout.

As artist Sonja Dahl has written about nongkrong in her study of the practice in Yogyakarta, central Java, and how this deep hangout is linked to the art scene and art production in Indonesia, nongkrong can be literally translated as “squatting by the side of the road with a cigarette” or “sitting around because you’re not doing any work”. The expression ties with the old pan-Indonesian habit, still visible especially in Jogja and Solo, to bring a carpet with you and sit down on an unoccupied side of the road or in a square, where successively drinks, food and cigarette are consumed, becoming the fuel to endless conversations, exchanges and reflections on multiple topics shifting swiftly from mundane accounts regarding one’s own family and friends to existential, endless discussions about art, life and spirituality. A particularity of these encounters is that they seldom happen in a set time like in the West. nongkrong surely has a starting time, although delayed by the constant being late of its participants but it never has a fixed ending. Complicit with the legendary hospitality, social responsibility, curiosity and sociability of Indonesians, nongkrong is a black hole where time is not a relevant quantity and explorations of personal and community bonds dictate this uncertain acquaintance interzone.

Nongkrong can be literally translated as “squatting by the side of the road with a cigarette” or “sitting around because you’re not doing any work.”

Therefore, though it is tempting to judge such activity as a waste of time, extreme, useless unproductivity, the process of nongkrong - essentially non-productive social time - serves a very important role in building social relationships in Indonesia. While on the surface it describes the simple act of hanging out, ‘hayu, nongkrong!’ it actually reconfigures the relationships between people, of bodies coming into space together, of social, mutual exchange and slow, relaxed time. Nongkrong is the low, almost imperceptible hum of relationships, an activity that acts as social “glue”.

Even more, if one talks to different music collectives around the city, one can see how nongkrong has often acted as a pivotal infrastructure which assured collaboration between different scenes, intergenerational knowledge transfer between more and less experienced musicians and the constitution of a social space where dissident political ideas could be explored and crafted, becoming the nexus of grassroots political activism. When discussing about the weakening of several music movement, it’s not rare to hear that such music phenomena are not pursued anymore because happenings like gentrification and the disappearance of public space coming after Indonesia after being successful in the West, have damaged the people’s ability to associate and nurture this social humus. Your dear nasi goreng warung is another airspace like the others, and getting in is expensive and boring. Yet, it’s hard to destroy an activity that does not require anything in particular, besides sitting on the road and enjoying each other’s company. The fact that nongkrong just asks for people to want to be with other people and to share each one’s resources to have a good time, makes it, perhaps, one of the most radical and anti-capitalist practices ever conceived.

A casual knowledge-sharing that many artists claim is more influential on their development than their formal educations.

The looseness and elasticity of time and place and people, actually, works as an incredibly valuable tool to let deep sociality happens. The fact that the “seize the day”, “time is money” rationale has no places here, allows for an open and generous exchange of ideas and information without a preconceived aim; a casual knowledge-sharing that many artists claim is more influential on their development than their formal educations. More in general, the liquidity of nongkrong allows subjects to hear and tell about the most disparate topics, from musical techniques and new releases to stories about the production of one’s tobacco, some particular food stall everybody loves or memories about superimpositions of places and people.

Therefore, standing at the opposite side of a time punctuated by the redaction of CVs and timestamp consumed meetings, breaking into Bandung's vibrant underground hangout isn't about filling out applications. It's about showing you belonging to others, often through unspoken rules and a bit of trial by fire. Let’s dive in the world of nongkrong and let me be your guide.

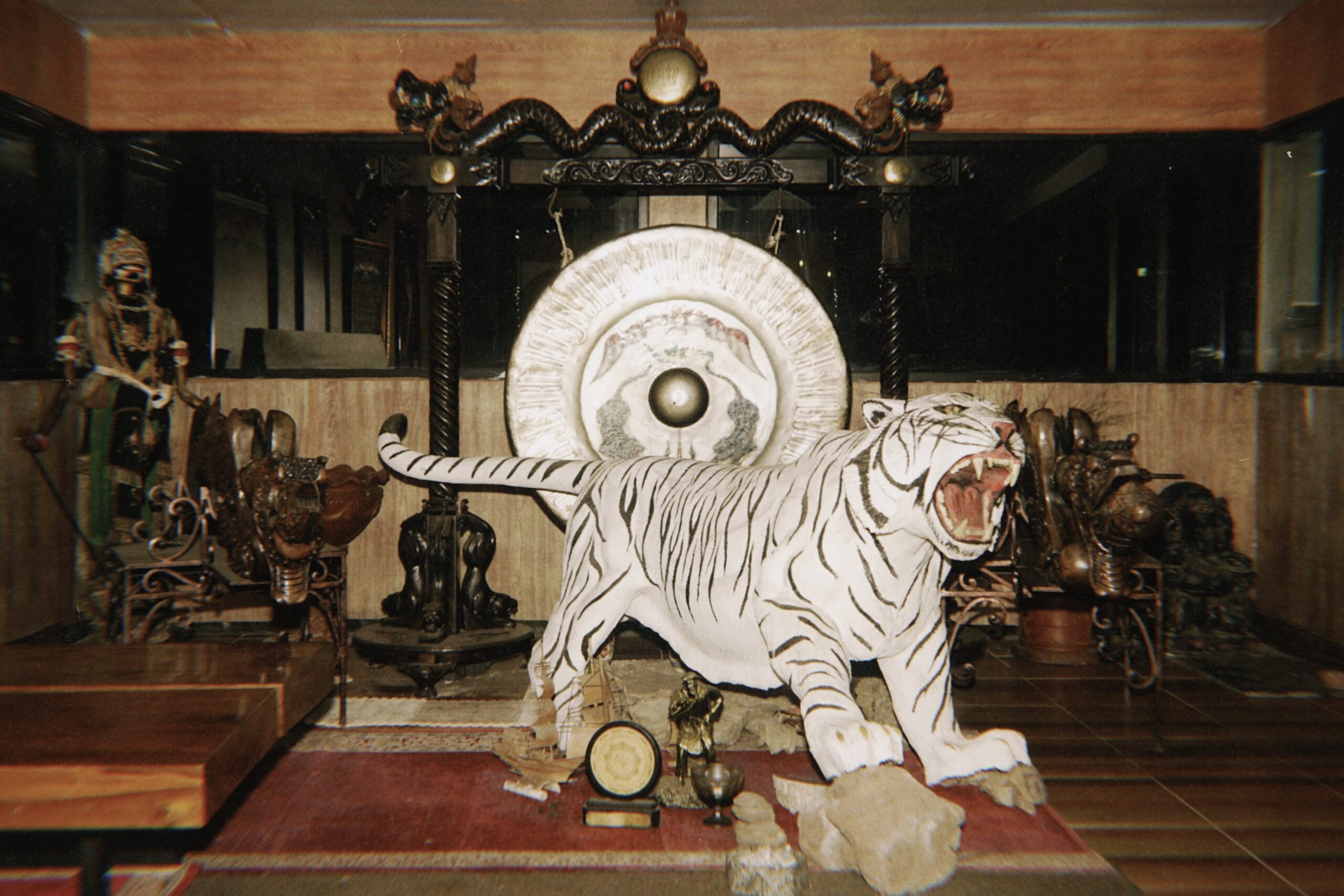

First of all, finding these hubs is not a matter of knowing the address, but understanding how people map living and lived space. These spots are often not on Google Maps. Pegman can’t help you here. It’s about that specific details: the shape of a certain road, a murales or a specific tree which tells you where to go. People will use these vernacular mapping systems ‘cause if you know you know and in nongkrong knowing and asking is a must. After that, the path is a multisensory dowsing system. Smell of certain things, piles and piles of music stickers on a door, and the sound that your people make when they’re together, perhaps even the smell and clangour of your peeps fixing a motorbike together. Again, it’s not about knowing in general, but it’s about knowing your people. How do they sound, smell and feel like? It’s an istinctual location system built around your kin. It’s a geography made of knowing and feeling.

Although the rules of these transient and ephemeral social spaces are still largely unwritten, this does not mean that nongkrong lacks a social structure. Also in the deep hangout, groups benefit from sort of positive gatekeepers, the guardians of the scene's history and authenticity. Take for example what I term the music hoarder or the Archivist. Although this may be just a food stall owner, and thus pass unobserved, they are often foundational to the community. They possess treasure troves of old demo tapes hidden away – relics from the tough times of the '98 economic crisis which they have amassed at the time or currently, in order to make sure that this particular story made of releases, patches and posters is kept, spreading into the new generation.

The archivist is then followed by the Smooth Operator or the Fixer. Do you need to navigate the local scene? Are you searching for something highly specific? Want to know where they practice that specific trance ceremony? This is the person who knows who to talk to, where to find what and how to access normally unaccessible things. Heck, sometimes they even know what kind of stuff will smooth things over with the authorities. Finally, one of the most important figures is the one of the OG or the Elder. Although this might not be someone in their sixties, they definitely were there first when things were happening. Still rocking that vintage '95 band tee, this veteran can spot a bootleg and a poser from miles away. They may judge you by the very laces of your shoes or just want to make sure you know the deal with the scene, but they are often regarded as the extreme authority on the topic. Usually, during nongkrong, you might know who this person is, since when they talk, everybody looks at them with full attention, while a minute ago everybody’s conversations were haphazard and everywhere.

Yet, although knowing the right people might help, in all nongkrong you have to earn your stripes. There's no fast track here, nongkrong is a practice that everybody can and have to learn step by step. It’s a bodily practice of living with others. You've got to put in the time and show respect. In order to learn how to enter the deep time of deep hangout, be sure to consign yourself to three main principles. Be sure to enter the space with the tenet of observe and absorb. Don't expect to jump right into conversations, This isn’t about one-upping, but about osmosis. Soak the signals coming from the others first. Show up a few times, share when you’re requested to. Often, how you are in space works better than how you describe yourself and your world. After all, your band t-shirt speaks volumes already, your body is your underground CV.

Of course, nongkrong is a practice of sharing resources, physical and cognitive. See this as a blood pact, a Symbolic offering. Bring something meaningful to share with the space and the people. A gift as a token of appreciation for the time you’re about to spend with the other – an old DIY magazine, food, a rare bootleg recording to listen to, or your last clove cigarette. It's a gesture of commitment and a way the space allows you to leave a trace of you into it. That token will circulate and expand through the people in the nongkrong and will multiply your heritage in the community. Of course, if someone gives you some kind of knowledge, be sure you’re offering something in exchange. That’s how scenes are built. If you know how to screenprint and the other is explaining to you some kind of esoteric tuning system, be sure to offer your expertise in return.

Bandung’s underground music scene isn’t just about the music—it’s a living, breathing culture built on community, resistance, and shared memory. The ritual of nongkrong is its lifeblood.

Remember: if you’re passing a kretek around, make sure it’s counterclockwise. No one knows why, but going against this principle is believed to be harbringer of bad luck.

And last, what would it be a community like without simple belonging tests? Knowing the right people it’s always an issue of symbolic capital. Belonging it’s cool but it has to be earnest and help others know where you come from and where you’re directed to. Put yourself to the test and show that you know some history. Yet, it’s not about facts, not about dates not about namedropping. If someone asks, "Kamu tau Rumah Pirata?" (Do you know Rumah Pirata?), they're not looking for a yes or no. They want a story, a connection to the scene. Nongkrong feeds on our stories. If someone at a certain point mentions they know the story as well, it means that your paths have crossed once already, and you were just waiting to arrive here.

CONCLUSION

Bandung’s underground music scene isn’t just about the music—it’s a living, breathing culture built on community, resistance, and shared memory. The ritual of nongkrong is its lifeblood, a sacred space where history is passed down, alliances are forged, and creativity thrives against all odds. Overall, Every warung debate, every shared kretek, every bootleg tape is an act of defiance against erasure. This is how Bandung’s DIY spirit survives gentrification, commercialization, and digital detachment. The scene lives only if the old guard teaches and the new blood listens. The moment stories stop being told—about police raids, stolen amps, or nasi kucin conspiracies—the scene loses its soul.

Bandung’s underground isn’t just music. It’s a fight for memory. And the nongkrong is where the battle begins.