Farmers in Corpse Paint

Extreme metal identity and ideology expressed through countryside imagery in West Java’

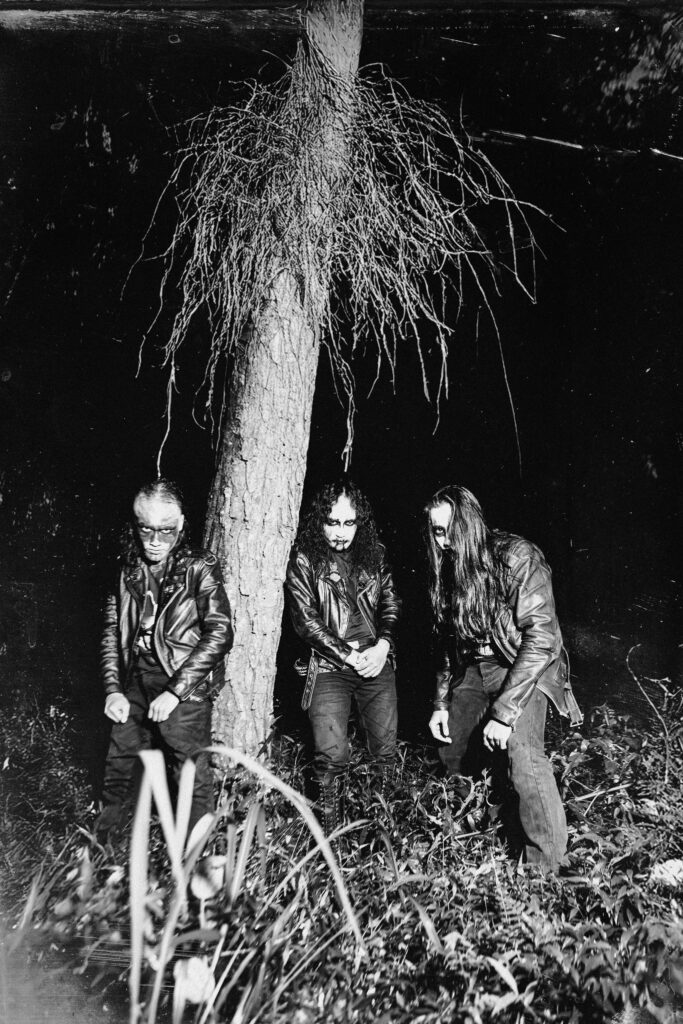

The black and white scenery depicts a quiet countryside made spooky by the bleak, duotone shades and nuances, sketched roughly like white noise emerging from the darkest of canvases. A rice barn is visible in the near distance. In the picture, only one figure: a peasant drives a plough through the misty field. His face, adorned with black metal corpse paint—a type of body painting that employs black and white makeup to make the wearer appear inhumane, demonic, or corpse-like—was invented and popularised by bands such as Mayhem, Mercyful Fate, and Sarcófago. I could swear it’s Gaahl’s face—the vocalist of the iconic black metal band Gorgoroth—ripped from the internet and photoshopped into the drawing. The gothic-style font says: Pemuja Sawah Tebu, “worshippers of the sugarcane fields.” This is the cover art of one of Bvrtan’s most recognisable singles; a band expanding black metal imagery beyond the monopoly of Scandinavian forests, into the West Java highlands.

When I first started researching the Bandung extreme metal scene, I was surprised to find out that, from Jasad to Undergod, Sufism, Tikus Kampung, Bvrtan, and Pure Wrath, these groups were at different levels appropriating and re-encoding images and aesthetics linked to the Java countryside. Although it was clear to me that these farmers, peasants, and folk figures were replacing the trolls, magicians, and warriors of imagined Scandinavian extreme metal traditions, it was still somewhat jarring to see Sundanese clothing and ritual-agrarian practices woven into the metal imagination. I remained puzzled, though, on why blue-collar individuals wearing leather jackets with spikes and showing off their t-shirts with brutally mutilated bodies and unreadable writings would solidarise and even identify with a social group like the farmers, which is so distant from them in spatial, temporal, and aesthetic terms. After all, I’ve never come across an agrarian worker in my research—certainly not one who was into metal music. Ancestors and farmers are better understood as imagined categories constructed by metalheads in Bandung and West Java, rather than actual social groups engaged with the underground scene.

When I interviewed Budi Dalton on this topic—a famous Sundanese actor, musician, and pillar researching the history and customs of the Sundanese people, and supporter of the local punk and metal bands—he told me that “rich or intelligent people from the country usually go out, learn, and come back, but they bring types of knowledge which push the culture far from his indigenous people: the farmers, the herders, the fishermen. They enter politics and lose that kind of focus on where we come from. Metal, conversely, employs music as a language that stresses the same points. It points at what is wrong in our world; that society and who rules it are broken.”

Generally, it’s always good to be wary of these kinds of narratives, which bring with them the perils of nostalgia and cultural enclaves, since such a rationale would leave out the possibility of striving for less gendered, parochial and gerontocratic spaces and relationships. After all, a less conservative approach and a more thoughtful understanding of how scenes are articulated can open up new spaces of empowerment by raising the unnegotiable noise of social unruliness, instead of falling back into statal and hierarchic cooptation. And yet, the merits of West Java and Bandung’s metal scenes are obvious and admirable. From a chaotic, geographic musical periphery with scant infrastructural access, they have managed to take part in a global movement of artists demonstrating that shredding and screaming can lift geographical borders, even only for a moment, while at the same time not giving up on their peculiar and often ethnological experience of place, past, identity, and language. But keeping the focus on Bandung would make this specific report too insular. It’s precisely when we widen our perspectives that we can deepen our understanding of the scene’s uniqueness. Particularly, following the trail of the countryside imagery, I’ll dive deeper into three projects—Pure Wrath, Bvrtan, and Sufism—currently using agricultural symbolism to articulate metal experience and imagery.

From a chaotic, geographic musical periphery with scant infrastructural access, they have managed to take part in a global movement of artists demonstrating that shredding and screaming can lift geographical borders.

Pure Wrath is the child of Januaryo Hardy, a composer from Bekassi and founder of one of the most popular atmospheric black metal projects in Indonesia. Since 2017, he has released three full-length albums that explore all dark corners of Indonesian history, including nature, death, and despair. The most recent, titled Hymn to the Woeful Hearts, was released by the French label Debemur Morti Productions, which has also issued records by bands such as Manes, Archgoat, and Blut Aus Nord. Originally launched as a solo project in 2019, Pure Wrath soon expanded to include numerous collaborations with musicians from the Bandung underground. They began performing live—embracing the greater creative flexibility offered by black metal over death metal. Ryo shows an advanced and extremely self-aware conception of what metal and music are and should do:

“Metal is a genre using shock and aggressiveness to convert attention to an extreme open-mindedness, getting you to think about important, even sacred matters. It’s that type of energy that makes you want to know more about the background and the lyrics.”

Pure Wrath channels this primaeval terror to explore themes that remain largely overlooked in contemporary Indonesian art: “From our second release onward, I began addressing issues rooted in Indonesian history, as my own family was affected by some of these events. You know, history is written by the winners, so I try to present alternative versions of Indonesian history—ones you don’t learn in school. It’s the younger generations who tend to be the most critical. I focus on specific topics and try to make them engaging, so young people feel encouraged to talk about them openly."

Whereas on most metal t-shirts and merchandise you can spot the usual brutalised body parts and a variety of casual, edge-lord imagery, Ryo’s artworks always relate to the Indonesian countryside, presenting the backs of anonymous agrarian workers in an ominous natural environment.

“For agrarian countries like Indonesia, they [the farmers] are fundamental; the grassroots population. Also, when it comes to colonialism, it was all about the farmers and their relationships to the colonisers,” he states: “But no one wants to be a farmer anymore, everyone wants to live in Jakarta and work in an office. For these reasons, I think that farmers are a way more important topic than ancient beliefs and the like.”

Of course, this type of heterodox approach has its price, especially in a country relying heavily on public funding and institutional support. As Ryo stresses, showing cultural features in metal productions makes it easier to tour and access government funding, especially thanks to ethnolocal bands like Jasad.

The portrayal of nameless peasants is weaponised as a means of direct criticism against the archipelago’s agrarian policies—policies under which rural communities, the “worshippers of the sugar cane fields” celebrated by the black metal band, have suffered most.

Although exceptional, Pure Wrath is not a unique entry in critical farmer-themed black metal (as if this could be a genre), making the pair somewhat of a “trickster twin.” Roaring from the hills of Depok, Bvrtan—a union of the terms buruh and tani, i.e. agricultural worker—is a unique project. Looking at the cover art and style, one can spot a Darkthrone parody—except that, instead of Nordic forest trolls, it features agrarian workers from the highlands of West Java, with nicknames like Penjaga Mvsholla (guard of the prayer room) and Kuli Arit (sickle labourer). With titles such as Ritval di Gvbvg Sawah di Bawah Kilatan Petir (Ritual in a paddy hut by the light of a thunder), Koperasi Kegelapan yang Memonopoli Ekonomi Pedesaan (The Dark Cooperative Monopolising the Rural Economy), and Tragedi Kegelapan dalam Serangan Tikvs ke Sawah Kami (The Tragedy of Darkness of the Rat Attack on Our Fields), Bvrtan have no less than seven albums under their belt and a few splits, including an EP with Norwegian Taake. All fun and games, if not for the fact that the Bvrtan are now blacklisted by the Indonesian state, thus having to use their monikers to keep their identities secret. The portrayal of nameless peasants is weaponised as a means of direct criticism against the archipelago’s agrarian policies—policies under which rural communities, the “worshippers of the sugar cane fields” celebrated by the black metal band, have suffered most. As Kvli Arit has stressed regarding this mix of parody, black metal, and Indonesian agricultural themes:

“Agricultural workers are our forebears and our main culture, so it’s similar to Scandinavian Black Metal. Moreover, focusing on farmers’ issues means confronting many of the core problems facing contemporary Indonesia. You see the stark contrast between the wealthy and those struggling to meet their basic needs. Yet, somehow, we remain resistant or even dismissive toward this tradition. This is because in Norway, everything’s good. Everything’s serious. Education is free, healthcare is free… Besides, this was the whole point of making Bvrtan. We wanted to make something that would have been impossible for a genre where racism defines what it’s like to be a metalhead. That’s why we are an ironic band, we want to be offensive to black metal and mock it.”

Bvrtan stands as an example of how metal and extreme sounds are sometimes used in Indonesia to ridicule higher powers and highlight the byproducts of power inequalities, such as land grabs and widespread corruption. If it’s funny, it doesn’t mean it’s not dangerous. Bvrtan created this carnivalesque, grotesque space of exploited farmers covered in makeup to smuggle an anti-hegemonic narrative hostile to both black metal hyperborean, as well as Aryan racism, Indonesia’s iron fist against subaltern, dispossessed lower classes. As Kvli Arit said:

“We hope that we can make people more aware of the problems that our nation is facing; the corruption, inequality, and violence. Finally, our will is for people to think farmers are cool. Or better, CVLT! through music. Lyrics are crucial because, through a parody band, by translating what we sing about, one can understand what it’s like being us and living our life.”

Going back to Bandung’s brutal death metal roots, Soreang band Sufism—a four-piece classic formation which has been active in the scene for a long time before releasing their debut album in 2020—represents another example. Republik Rakyat Jelata (Republic of the Commoners)—a title highlighting the music’s class perspective—depicts a serene countryside scene where women and men work side by side in traditional markets or return from fields and mountains, some dressed in traditional attire as they oversee the landscape. Although grey clouds are ominously populating the sky, the setting is tranquil, in a way reminiscent of the polar opposite of Pure Wrath’s cover art. Other artworks also seem somewhat optimistic, portraying alternative kinds of peaceful traditional scenery. Yet, this only makes sense in contrast with a life like the one in a rich peri-urban area like Soreang. A life both linked to agriculture and increasing industrial processes, progressively reducing the availability of land and the agrarian workforce. As Nanang, frontman of Sufism, confirms:

“Soreang was all countryside until the early 2000s. Talking about our surroundings and the people who live there felt natural. We became interested in agricultural life and the social issues faced by these communities. Unlike Jasad, we focus more on the tangible realities. Farmers stand at the crossroads of social politics and culture. Here, many sell their land cheaply to get quick cash. And for those who work at the factories, like the other Sufism members, the problems are the very same: to fill their bellies.” Alongside observations that class issues affect both factory workers and farmers alike, Bvrtan incorporates agrarian imagery inspired by Sufism, aiming to instil pride in farmers for their role and celebrate their connection to ancestral lineages.

Despite incorporating nostalgic undertones into their music, Sufism’s metal visual artworks paint an alternative and long-gone reality for a country in which the first and second sectors of production and manufacture are undergoing the same massive shifts, compromising the human condition of many dwellers.

Ultimately, the presence of bands like Sufism, Pure Wrath, and Bvrtan demonstrates the metal imagination’s flexibility—showing how it can be wielded as a powerful tool to challenge local injustices. As we look at these covers and smirk cynically at their off-beatness, perhaps thinking that it’s all absurd—from the landscape laden with palms to the non-threatening nature of the depictions—we also catch ourselves duped by metal’s reactionary ideological ground. If trolls are almost certainly not real, these struggling individuals wounded by history and the global market definitely are. Traditionally, otherworldly creatures have populated the escapist metal imagination; an imagery full of power tropes often feeding on made-up historical and racial theories about, for instance, a white, forlorn Scandinavia. Yet, the screams coming out of the tropical jungles and the rice paddies, the bamboo groves and the sugarcane fields, now peri-urban settlements reuniting people from various walks of life, are not of this order. They belong to real humans trying to survive the conditions of global capitalism ravaging the lands and transforming everything into tarmac and metal.