“You are you, I am me, and I don’t care what you did to end up in prison.”

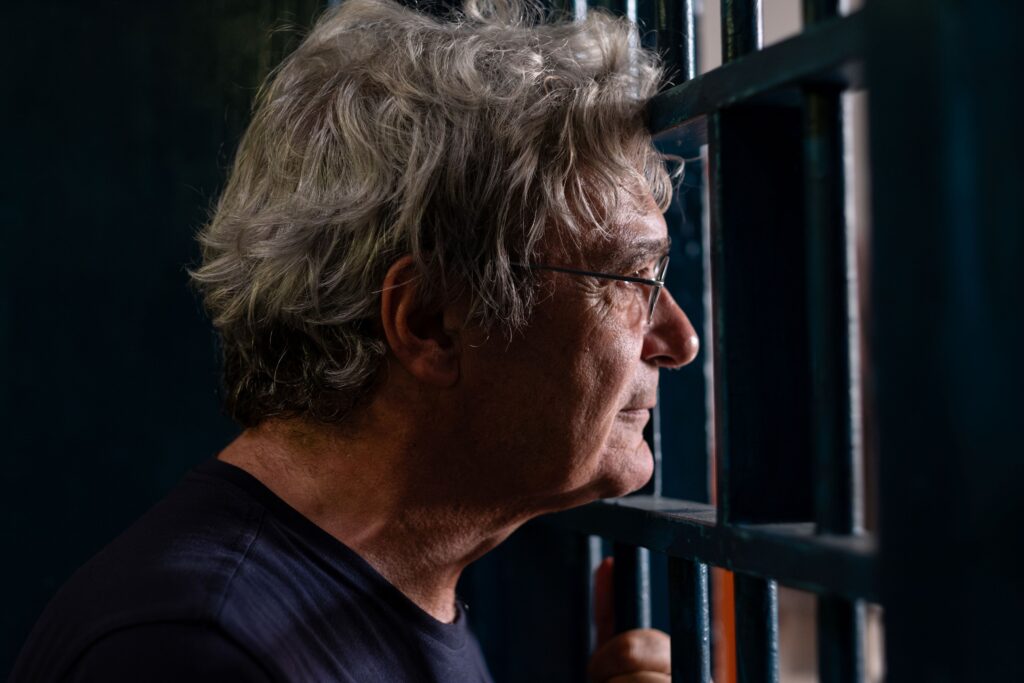

“Prison regresses you to childhood, I think as I wake up. Does it do this to everyone, or only to me?” writes Goliarda Sapienza in her autobiographical novel L’università di Rebibbia. She goes on to describe the arrival of the guard who opens her cell door: her step is electric, something Sapienza is no longer used to. She comes from ‘outside’ yet works ‘inside’. It is as though Sapienza is slowly, unexpectedly discovering a new harmony with different tempos: the tempo of isolation (the inside-inside), the tempo of the shared cell (the inside), the tempo of the hour in the yard (the inside-outside), and finally the world we all inhabit every day (the outside). This constricted space and fragmented, frayed, confused sense of time are rendered in the often-elliptical sequences of Mario Martone’s latest film, Fuori, drawn directly from Sapienza’s writing and shot inside Rebibbia prison. It is a labyrinthine film in which the story of friendship and exploration between the writer (Valeria Golino) and two inmates she meets in Rebibbia, Roberta (Matilda De Angelis) and Barbara (Elodie), unfolds in determined disorder for two hours.

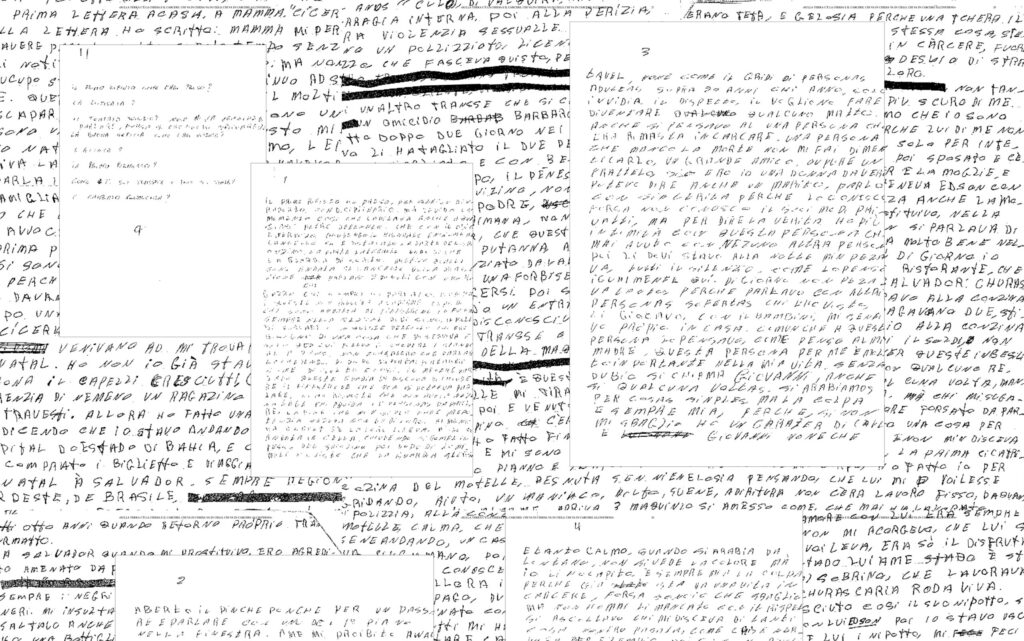

The writing is first and foremost thanks to Ippolita Di Majo [the screenwriter, Ed.]”, Martone notes, “who has worked on Goliarda Sapienza for a long time, including a theatrical adaptation of another of her novels, Il filo di mezzogiorno. Fuori is a project that has come a long way. When I start from a writer’s pages, it’s important to me to stage what is told, but also how it’s told. And therefore the digressive nature of Goliarda: she wanders off then re-centres herself, she’ll toss off crucial narrative details in a single line, then veer into wide new directions. I wanted the film to have that drifting quality, that tendency to wander that is intrinsic to her writing.” At the centre of this emotional universe sits the relationship between Goliarda and the young Roberta, a bond in constant flux: friends, lovers, but also mother and daughter. An unpicking of emotional and social relationships that appears too in The Art of Joy. Martone says it was precisely “the relationship between Goliarda and Roberta that pushed Ippolita to frame the story in this way. It’s a form of the feminine that, in certain respects, feels entirely new. In the film, you never know whether the love between Goliarda and Roberta was also physical, and the truly interesting thing is that this question doesn’t matter. It’s a new form of the female friend-lover relationship. Goliarda writes within a world and a literary tradition where every love story revolves around possession, which also means carnal possession. Here, instead, there is a kind of real freedom.”

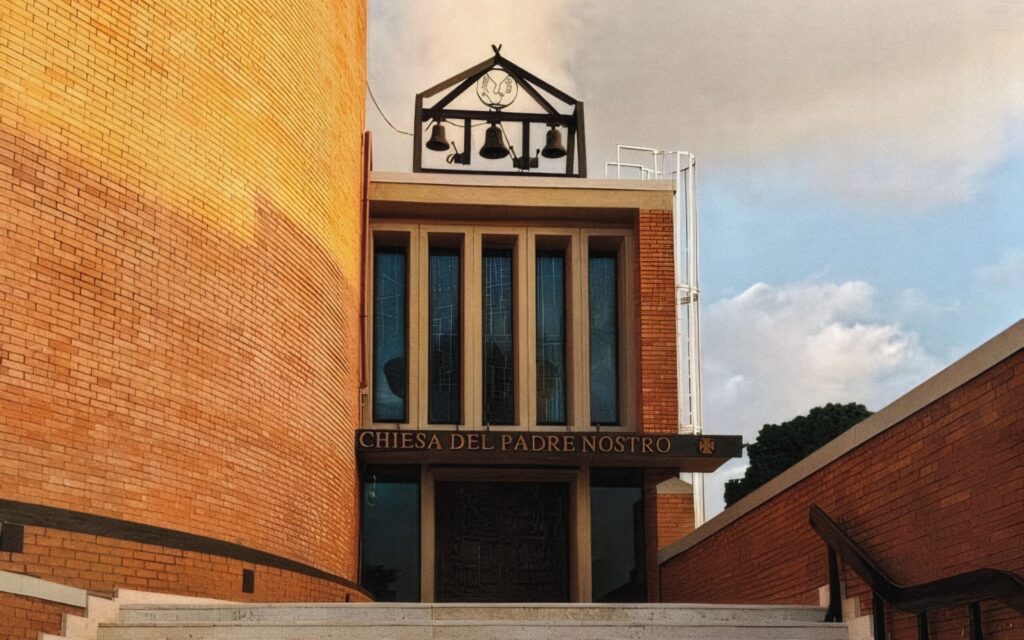

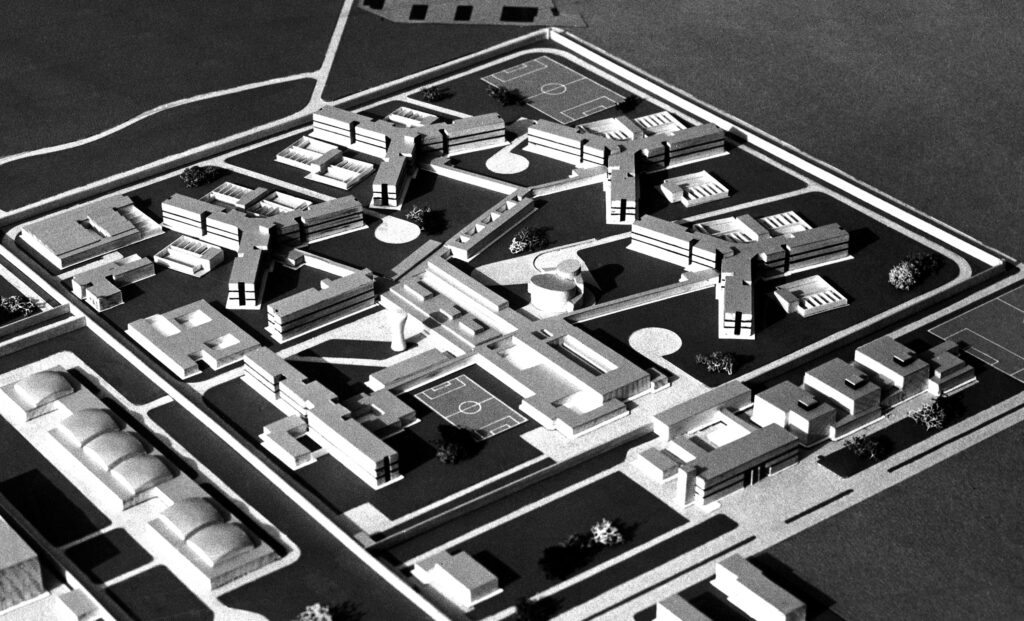

This freedom is something Goliarda discovers in what she calls “the university of Rebibbia” during her time in prison. In both the book and the film, the focus is not the writer’s biography but her inquiry into spaces—an inside and an outside that eventually converge—starting with Rebibbia itself. Martone’s cinematic approach in Fuori grapples with a problem tied to the nature of the gaze: how to film a total institution without merely confirming its separateness, without reinforcing the barrier between the ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ that Sapienza seeks to dismantle. Filming inside Rebibbia was an unusual choice that makes the visual material more vivid and immersive. “In the way I work, it’s very difficult to imagine not having a direct relationship with the locations. For me, it’s crucial not only to achieve verisimilitude but also to capture the truth of the film’s elements.” The screenplay, based in part on L’università di Rebibbia, demanded a specific place, far removed from the nineteenth-century imagery of many prisons: “Rebibbia is a modern prison, opened in the early 1970s. We could never have filmed in a decommissioned penitentiary, which is often how it's done.”

“What I asked for and obtained was the involvement of the inmates in the scenes as paid professionals. It couldn’t be a matter of ‘stealing images’, but of creating direct involvement.”

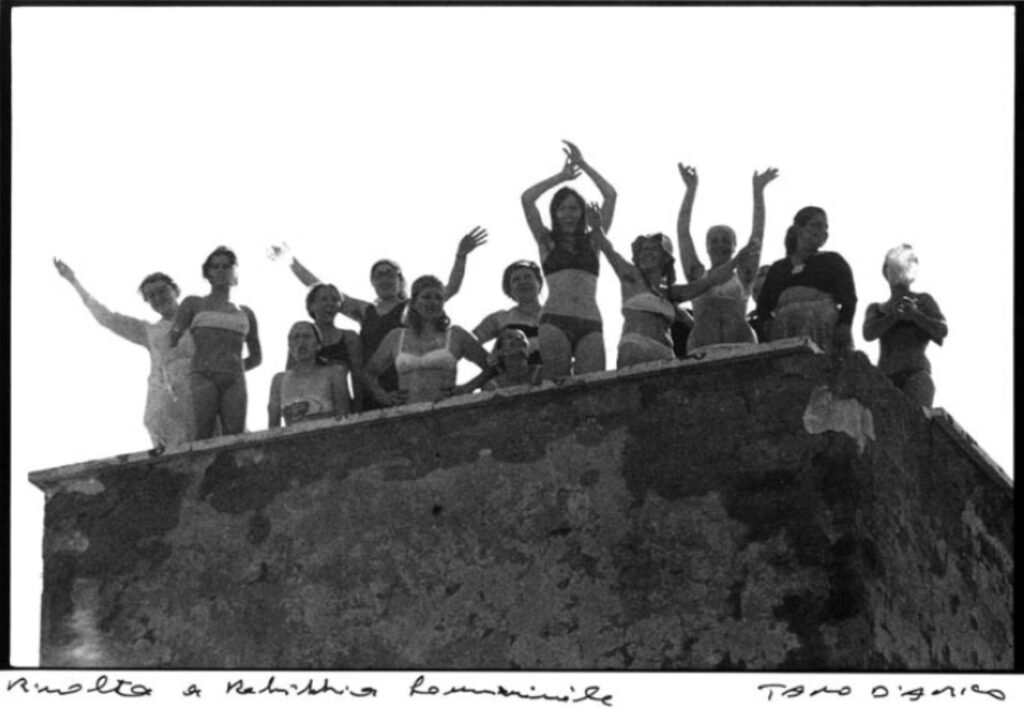

Access was made possible thanks to Francesca Tricarico, who runs the theatre company Le Donne del Muro Alto at Rebibbia. “She was the person who introduced me to Rebibbia because she knew the environment and had years of experience inside the prison.” What followed was a long, bureaucratic process to obtain the necessary authorisations. “What I asked for and obtained was the involvement of the inmates in the scenes as paid professionals. It couldn’t be a matter of ‘stealing images’, but of creating direct involvement. I wanted to rely on their collaboration as actors, as supporting cast—even to gain elements of truth I would never have obtained otherwise.” This approach created a fertile, vibrant environment on set: all the actors playing Sapienza’s cellmates are inmates or former inmates.

A particularly emblematic scene takes place on the walkway: a space full of voices, colours, and whispers, where Martone paints a fresco that is both tender and violent. Sapienza fights with another woman; some inmates cheer, others are indifferent and only want a bit of sun. The walkway at Rebibbia resembles the courtyard of any Roman housing block where the newcomer is first scrutinised (especially if she wears silk blouses), then immediately invited to lunch. Martone’s gaze meets Sapienza’s at eye level, offering a way of looking that is curious rather than judgemental. The issue of judgement mattered deeply to the director who, after the screening at Cannes, returned to Rebibbia to show the film to the inmates. “It was a very powerful, moving screening, and important for me, because it was an audience whose opinion I cared about.” The most meaningful reaction came from one inmate: “She said something wonderful: ‘I watched this film for two hours and never felt judged.’ That struck me enormously. It was perhaps the best thing anyone could have said.”

If the prison is the film’s body, Goliarda Sapienza is its nervous system. Martone portrays her at a moment of existential and creative crisis, radically transformed by the experience of detention. Sapienza writes of a “regression to childhood”, a state of freedom and of seeing the world anew. This is not infantilisation but access to a pre-social mode of communication stripped of bourgeois superstructures. A paradoxical code emerges: one can speak with brutal frankness, then show solidarity an instant later—just as children do. It is a heterotopia in which the condition of imprisonment becomes, for the writer, a liberation from the past. “Her writing, which had in some way ground to a halt after The Art of Joy, the disappointments, and the book’s failure to be published, no longer flowed. Coming to Rebibbia—this kind of regression to a direct, unfiltered level of human interaction—meant discovering a vital Roman dialect. This is why the Romanesco is so important in the film.” When she enters prison, Goliarda meets women who dismantle the social masks of the world that rejected her. “She finds direct relationships. Hence: ‘you are you, I am me, and I don’t care what you did to end up in prison.’ Even being in prison, paradoxically, frees her. You’re in prison because you committed an offence, full stop. Once you’re there, the offence no longer exists because you’re serving your sentence. That resets relationships.” This experience allowed Goliarda to dismantle the generalisations through which bourgeois and intellectual society perceived the prison world. Her own words echo this. Interviewed by a paternalistic Enzo Biagi in a clip shown at the end of the film, she reflects: “Inside, the individual is so transformed that prison becomes their home; and it’s like when our home doesn’t quite please us—there’s no sun, or it’s cold—but we get used to it. And so for them too, prison becomes their place […] I’m not saying prison is pleasant, but prison is like the outside.”