The Electronic Hybridisation of Lusophone African Music and Sonic Globalisation in the Batida of Quinta do Mocho in Lisbon

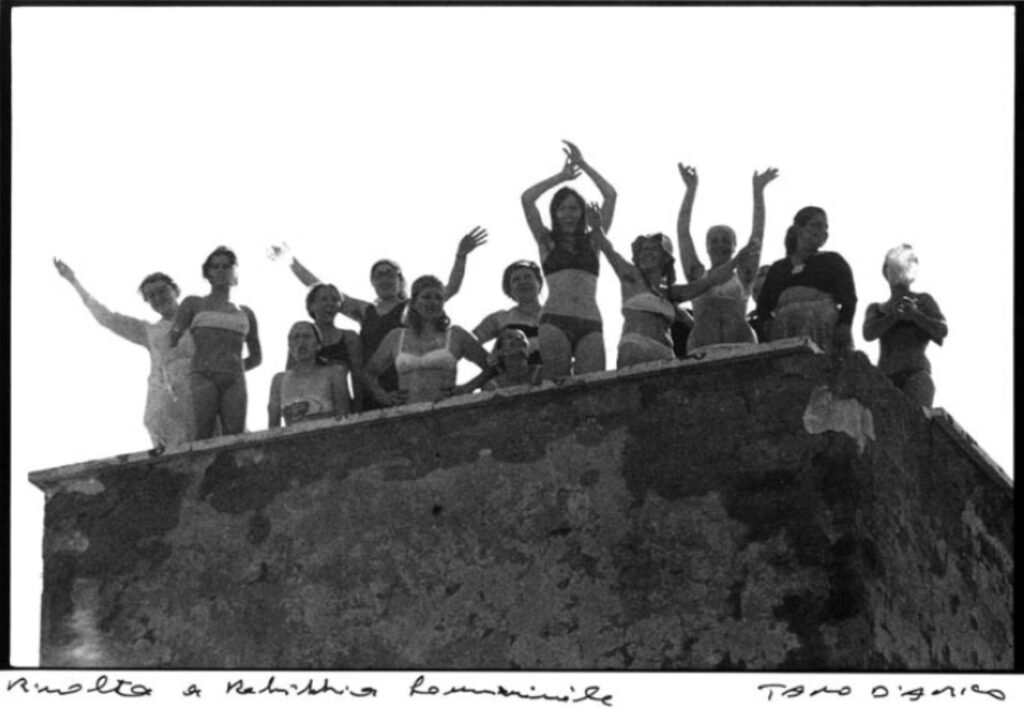

I was never part of the Noite Príncipe crowd, nor did I hang out in Lisbon’s suburbs. I wish I could say I was there when the legendary label, Príncipe Discos, became a regular at Musicbox, one of the pillars of Lisbon’s nightlife, and present during the early experimentations of Batida’s pioneers, witnessing unheard sonic entities take shape on software cracked on low-cost computers. Stepping into one of Príncipe’s photographer Marta Pina’s early portrayals: a Sunday lunch community gathering in the courtyard gardens of a residential complex on the city’s outskirts. Suburban skyscrapers as the default visual background; a reverential and equally sweaty audience dancing through their first revelatory exposure to Batida; bedrooms shaded by drawn blinds and crowds gathered around a computer screen running FL Studio.

It might not have been in its birthplace, but I did get to experience Batida a few years after these pictures were taken. The whirlwind of sinister, percussive beats cast a spell on me. Body and soul absorbed, I let my gelatinous limbs go free. My haunted dance responded to Vanyfox’s DJ set, one of the talents from the widely acclaimed Montreal-based collective Moonshine, and a leading voice among Batida’s youngest generation of artists. Self-described as a post-border, multidisciplinary music collective focused on African and Afro-diasporic club culture, Moonshine serves as a golden bridge between this music legacy and the various cities it regularly tours. It’s indeed thanks to their event at Dock B in Pantin on that Parisian winter night that I was first exposed to Batida, through Vanyfox.

Batida is an umbrella term standing for the multitude of results emerging from the encounter of regional styles from Lusophonic African countries and European electronic music.

According to Daviaa, Anglo-Portuguese producer and founder of the great radio show Na Tchada at Reprezent Radio, Vanyfox belongs to a long list of emerging and highly talented artists pushing the boundaries of Batida into unpredictable and equally fascinating directions. There’s DJ Tyson, part of a new trend slowing down the usual Batida’s 140 bpm; Danifox and Lycox, experimenting with adding vocals on the beats; Dariiofox, the closest to the original sounds of Batida, influenced by his brother DJ Nervoso; Nuno Beats and DJ Narciso, members of the more experimental RS Produções, mastering tension and release—and so on. Most are under Príncipe Discos, the Lisbon-based record label showcasing contemporary dance music from the city, its suburbs, and slums; widely recognised, and rightfully so, as one of the most exciting dance music projects on earth. Príncipe’s signature is Batida, an umbrella term standing for the multitude of results emerging, in short, from the encounter of regional styles from Lusophonic African countries and European electronic music.

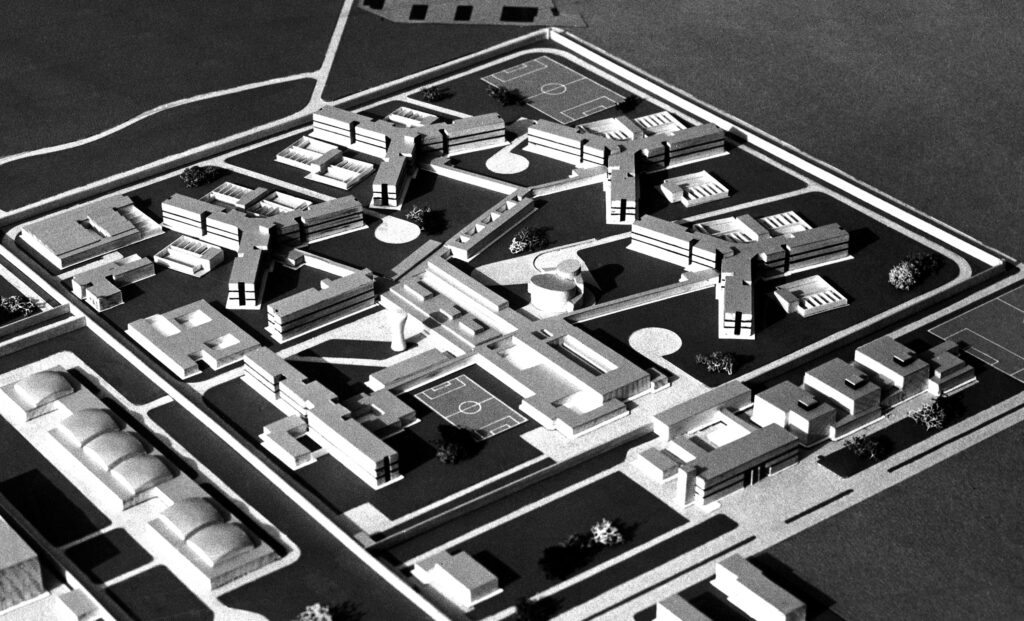

With its geographical inception deeply rooted in Lisbon’s suburbs, Batida’s multifaceted sonic identity began to emerge amid the electronic music fervour of the early 2000s. In its early form, the emerging genre was an artisanal blend of Angolan kuduro and other African styles brought to Portugal by the Lusophonic diaspora, mixing with the new possibilities offered by the democratisation of early digital audio software. We could say that it all began with DJs Di Guetto Vol. 1, the first album launched in 2006 by a group including DJ Nervoso, DJ Marfox, and DJ Firmeza; all residents of Lisbon’s peripheral neighbourhoods, from Quinta do Mocho, now considered the scene’s cradle, to Quinta da Vitória, Baixa da Banheira, Queluz Massamá, and Barcarena. The compilation, available for free download online, spread widely and rapidly. It didn’t take long before they were invited to play in other European countries, soon expanding Batida’s outreach beyond the Portuguese capital.

The compilation was strategically released in September, starting the school year. Most of Batida’s pioneers were still in school when they laid the foundation for the genre, using cracked versions of FL Studio. Although they were still rare commodities, computers slowly became more available in the early 2000s, either at school or at friends’ houses. Amid the excitement of accessing early DAWs, DJs Di Guetto used this newly accessible technology to piece together the sonic influences they had been exposed to as members of Afro-descendant communities living in Lisbon’s peripheral neighbourhoods. These included first, second, and third-generation immigrants from Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, and São Tomé and Príncipe—all countries with a shared colonial history with Portugal. To grasp Batida’s role as one of the most significant contemporary sonic scenes, it’s crucial to understand its broader cultural context, starting with one of its main ingredients: Kuduro.

In the late ‘80s or early ‘90s, Angola was navigating the intermittent civil war that followed its independence from Portugal in 1974. Ceasefires saw Angola’s middle class travelling to Portugal and the rest of Europe, growing post-colonial exchanges between the two poles. As recalled by researcher Gerth Sheridan, this exchange introduced Luanda’s youth to a whole new array of imported recordings—found in street-side markets, clubs, and raves—and musical instruments. Soon enough, the emerging house and techno scenes taking over Europe influenced Angolan clubs, where DJs began incorporating these genres alongside American pop, and regional styles like kizomba and zouk.

Kuduro, which translates to “hard life” or very idiomatically to “hard ass,” emerged when producers took the next step by mixing genres, creating a new sound that would soon become part of the soundtrack of the final years of the Angolan civil war. As reflected by its lyrical bits, kuduro represented an outlet, through which to hope for a better future for the country; a sort of glue contributing to strengthening national identity. Angolan history and African media studies scholar Marissa J. Moorman importantly notes that kuduro has frequently been dangerously co-opted by governments and military officials for their political agendas. The genre reached cross-class popularity when working-class Luandans created their version—faster, harder, and with lyrics that articulated the experience of living in the musseques, Luanda’s shanty towns.

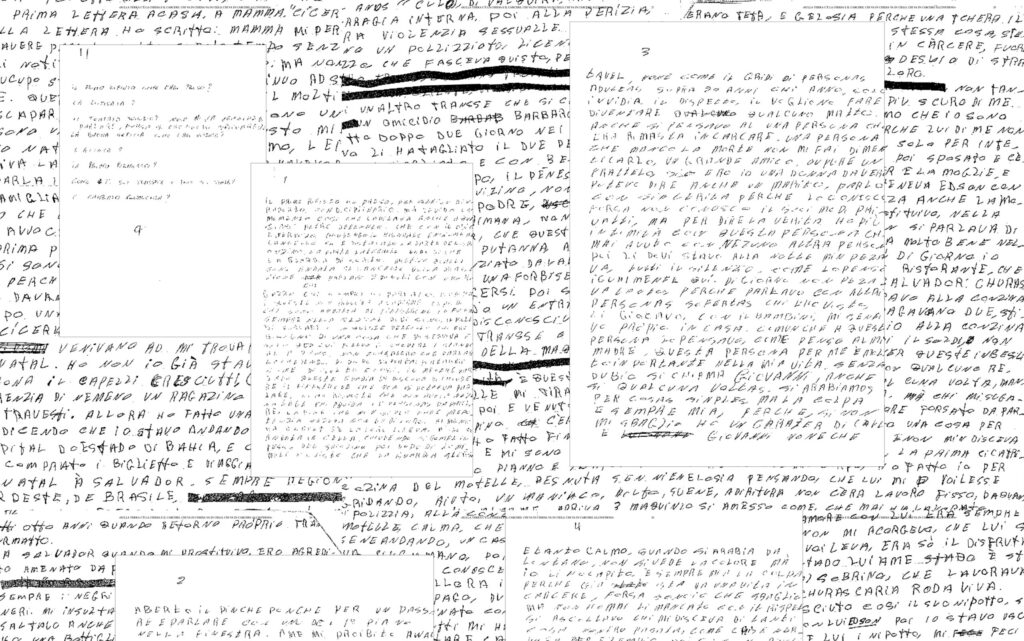

“Car horns, fire alarms, percussive sounds, and indistinguishable chatter in Portuguese, Cape Verdean Creole, and Angolan slang”—much like an archive, as sociologist Otávio Raposo puts it, the neighbourhood’s atmospheric acoustics sampled in Batida’s tunes play a fundamental role.

Kuduro was the main regional sound behind Batida, but not the only one that contributed to the genre’s frenetic rhythms. Aside from European influences, uptempo kuduro merges with Angolan tarraxinha, Cape Verdean funaná, and zouk—musical styles rooted in various Lusophone African regions which coincide with the Afro-descendant diaspora in Lisbon. Reversing the trend of the European scene influencing the birth of kuduro in Luanda, this diaspora’s cultural and sonic heritage became a core element for Batida’s pioneers. Diasporic configurations and their geography are thus intrinsic to Batida’s identity.

The creation of Príncipe Discos by Márcio Matos, José Moura, Nelson Gomes, and André Ferreira marked a definitive turning point in the scene’s internationalisation. The label launched in 2011 with DJ Marfox’s debut Eu Sei Quem Sou, which set the tone for Príncipe’s sonic identity and direction. That same year, Marfox became a key link between Príncipe and the peripheral neighbourhoods where Batida was gaining traction, recruiting the most talented and diverse emerging voices in the scene. Among the first recruits was DJ Nigga Fox, whose first release O Meu Estilo, according to Matos, signified a crucial juncture for the label, capturing the audiences’ attention. Following this, Nídia, DJ Firmeza, and DJ Nervoso joined the scene. By the mid-2010s, Príncipe DJs were streamed transcontinentally and performed at Sonar, Roskilde, and New York’s MoMA.

However, the scene’s identity remains closely tied to its geographical origins and the cultural and sociopolitical dynamics it embodies. “Car horns, fire alarms, percussive sounds, and indistinguishable chatter in Portuguese, Cape Verdean Creole, and Angolan slang”—much like an archive, as sociologist Otávio Raposo puts it, the neighbourhood’s atmospheric acoustics sampled in Batida’s tunes play a fundamental role. This “layer of sonic information” has the power, according to the researcher, “to inscribe silenced histories” and “systemically excluded bodies” into Portugal’s narrative and public sphere. As DJ Marfox once told Raposo, “My music brings identity and certainty to a group of young people who don’t fully identify with anything. This group identified with this batida because it was something new, not fully African nor European.”