The “Cucina Economica”

The story of the Circolo San Pietro, which has been serving the “Pope’s soup” for over 150 years.

On April 29, 1827, Hussein Dey, Ottoman governor of Algiers, decided he had had enough of the excuses made by the French consul Pierre Deval and slapped him with a fly whisk, commonly referred to as a fan (under which name this incident became known in historical records). This was a story of food supplies and unresolved cyclical debts dating back to the time of the French Republic, which immediately escalated into a naval blockade in retaliation for the insult. The blockade, however, proved ineffective, and on July 5, 1830, the fleet of the Kingdom of France, commanded by Admiral Duperré, began bombing the Regency of Algiers to settle the matter once and for all. During the battles and the subsequent phase of territorial annexation, the French came into contact with some Berber tribes called Zwawa, originating from Greater Kabylia, known for supplying soldiers to Ottoman militias. These Zouaves eventually became a military corps in the French army, with recruitment shifting exclusively to Europeans within a few years. In the same vein as the French Zouaves, the Papal Zouaves were established in 1861: similar in their clothing - the famous wide-legged trousers still referred to as “zouave-style”- and in their origins, as this regiment was mostly made up of volunteers from France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Their mission was to defend the Papal States against military attacks and the unification efforts of the Kingdom of Italy. The Zouave corps lasted about ten years and was disbanded immediately after the Capture of Rome in 1870.

One year earlier, a group of young men from the papal aristocracy, who regularly gathered at Palazzo Lancellotti on Via dei Coronari, decided to act on their shared desire to support the poorest members of society while fostering Christian education. They requested an audience with Pope Pius IX to present their idea and obtain approval to formalise their group. The pope's consent was immediate, and thus, in 1869, the Circolo San Pietro was born. It was the first volunteer organisation within the Vatican. Just days before the Battle of Porta Pia, Pius IX summoned the newly formed congregation to present them with the military cooking pots of the Papal Zouaves. He accompanied this gift with (approximately) the following words: “I may no longer have an army, but you will always have an army of poor people.”

"I was hungry, and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty, and you gave me something to drink; I was a stranger, and you welcomed me into your home."

Since its founding, the Circolo San Pietro has remained steadfast in its charitable mission to provide food for the most destitute segments of the population. It established what were known as “cucine economiche” (affordable kitchens): a term widely used in the 19th century during a period of fast and harsh urbanisation and industrialisation. These were essentially community kitchens offering meals at very low prices, often run by charitable organisations, religious institutions, or funded by philanthropists. Circolo San Pietro’s first cucina economica opened in 1877 on Vicolo Orbitelli, at the entrance of Via Giulia, close to San Giovanni dei Fiorentini. From that moment on, the Circolo’s meals became commonly referred to in Rome as “la minestra del Papa” (“the Pope’s soup”). These meals were served across the city, as the cucine economiche were neighbourhood-based and widely distributed. On average, around twenty kitchens were operating at any given time, but during certain periods, the number reached as high as eighty.

The Circolo has always devoted itself to providing support and hospitality, both in everyday life and in times of crisis. This was evident during the aftermath of the Marsica earthquake in 1915, which brought many displaced people to Rome, as well as during both World Wars. Even during the First World War, despite the battles being fought on distant fronts, Rome experienced severe hardships. In those years, the number of meals provided shifted from thousands to millions. In the 1930s, the Circolo also offered its support to the Venetians working to reclaim the Pontine Marches. Members would set out with oxen and priests, conducting catechism sessions or simply celebrating Mass in what were then virtually uninhabited areas.

Over the years, the Circolo’s activities have been organised into various branches (called “opere”), with the cucine economiche remaining at their heart. These canteens, the first tradition and a defining feature directly rooted in the Pope’s wishes, are upheld with great pride. Currently, there are three active kitchens located on Via della Lungaretta in Trastevere, Via Adige (in the Trieste neighbourhood), and Via Mastro Giorgio in Testaccio. The one on Via Mastro Giorgio was established in 1890. Initially based on Via Aldo Manunzio, it later relocated to its current address, in a building that was eventually purchased outright. Its entrance is marked by a marble plaque displaying the Circolo’s emblem in red: the Chi Rho, or Christogram, composed of the overlapping first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek: X (for “ch” in the Latin alphabet) and P (for “r”), along with the unmistakable inscription Cucina Economica.

Every year, the three kitchens provide an average of over 40,000 meals, served at lunchtime daily: from Monday to Sunday on Via Adige, and from Monday to Saturday on Via Mastro Giorgio and Via della Lungaretta. The kitchen on Via della Lungaretta did not even close during the Covid emergency, quickly organising to distribute meals in containers and bags. Up until about twenty-five years ago, the kitchens always relied on nuns from various religious orders to prepare meals, along with the collaboration of the Circolo’s own members. At Testaccio, for example, the strongest connection was with the sisters Suore figlie della Divina Provvidenza, whose convent faces Via Volta, Via Galvani, and Via Zabaglia. “When we were the ones cooking, it often happened that we did things out of improvisation. We’d call out to a nun in that same moment to make an extra carbonara or add another kilo of pasta for the incoming people. Poverty back then was much more Roman, and being in the kitchens felt like being at home”, recalls Augusto Pellegrini, a member of the Circolo who heads the cucine economiche commission.

Every year, the three kitchens provide an average of over 40,000 meals, served at lunchtime daily.

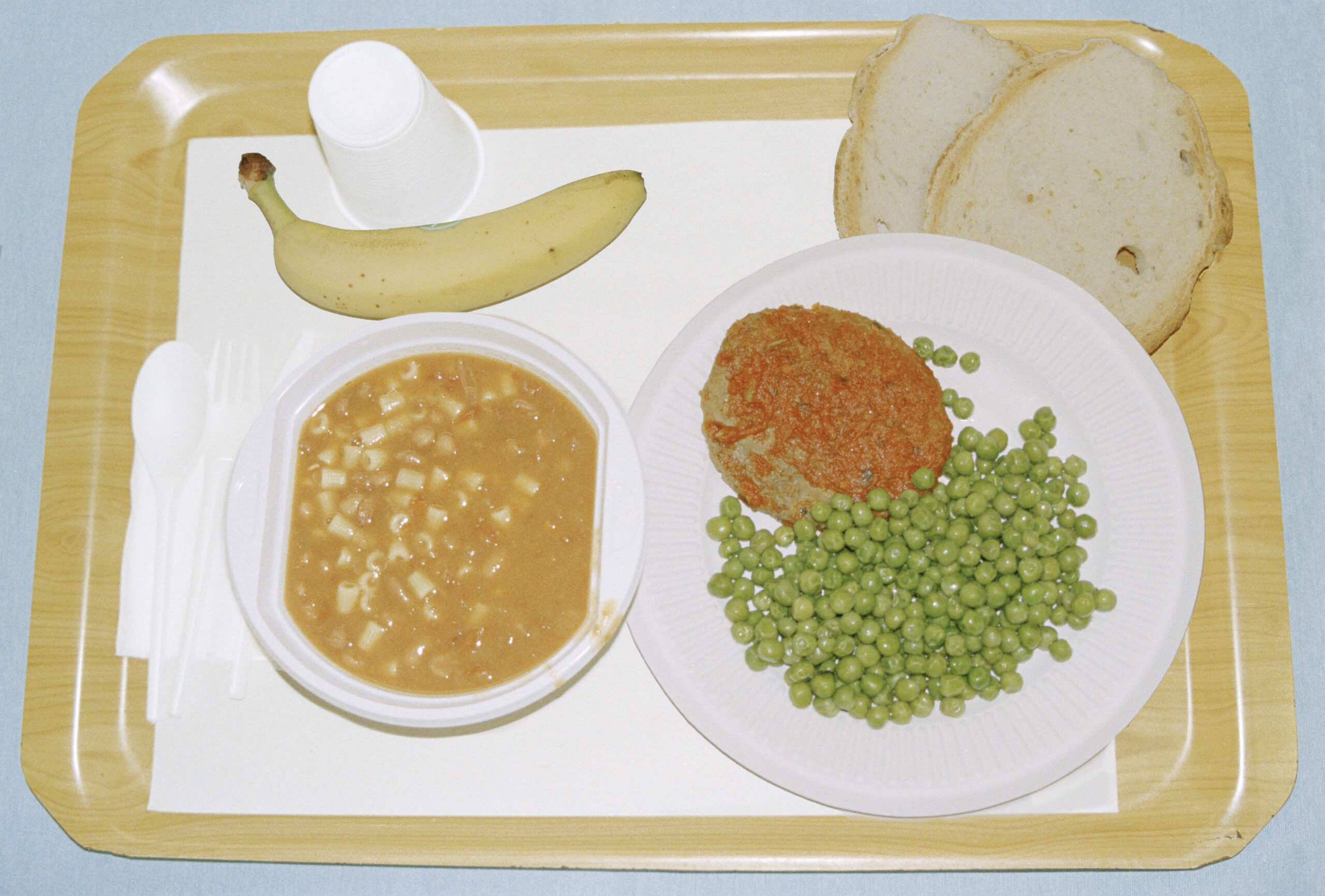

Now, the only canteen where meals are prepared by the members themselves is the one on Via Adige, and the communications are about dietary restrictions or religious prescriptions of the guests, indicating what foods can or cannot be admitted. At Trastevere and Testaccio, however, a catering service (Vivenda) is used, offering two options for each dish on the daily menu (typically a first course, a second course, a side dish, fruit, and often dessert and coffee, the latter courtesy of some members’ initiative), so that everyone can be fed: “In 150 years, the geography of poverty has changed. Our guests, who used to be primarily Romans or from nearby regions, now come from all over the world, with non-Italians prevailing in numbers”.

At Testaccio and Trastevere, however, the Italian share of the guests is still significant, if not dominant, because of the presence of long-term residents who live in the neighbourhood: “Sometimes we host people who live near the kitchen. They have a home and a small pension, but either because they’re alone or trying to save money on meals, they choose to come to the canteen. Of course, the social fabric of these neighbourhoods has changed, but situations like these still exist”.

Each kitchen always has volunteers from the Circolo: this is a key aspect since the goal of this activity is not only related to food, but also to human connection. Their presence ensures dialogue, listening, and understanding, and even a bit of order with particularly hungry or impatient guests! For the same reason, it was recently decided to renovate the Testaccio location, adding colourful elements and a few comforts, such as phone charging stations, since now phones are owned by most of the guests.

Before the COVID pandemic, there was also the option to pay for a meal with cash, at a symbolic price of €2.50. This amount was important because it gave guests the dignity of a meal that was given rather than begged for. However, this practice has since been interrupted for various reasons, starting with the fact that food was ultimately provided to everyone, even those who only had a few cents in their pocket instead of the full amount.

It gave guests the dignity of a meal that was given rather than begged for.

Moreover, as one might imagine, payments from the guests were entirely insignificant for the Circolo’s finances. Before each meal, prayers are recited: “Oremus Pro Pontefice Nostro”, “Ave Maria”, “Padre Nostro”, “Gloria”, and “Sancte Petre” to maintain the Circolo’s strong connection to the Church and the Pope. This bond is deeply rooted, further strengthened by the tradition of members who later became Popes, such as Paul VI, Benedict XV, and Pius X.

“The cucine are a tradition, a way of remaining faithful to the Pope and to a mission that we still feel is ours. We care deeply about this, just as we are always very careful about the quality of what we serve and the satisfaction of our guests, that’s why we always ask for their feedback and have an open dialogue with everyone”.

Circolo San Pietro activities extend beyond this, to various areas of poverty and need: “Since 1888, the Popes have called on the Circolo and its members to serve as an honour guard at the Vatican. These are the individuals who welcome attendees during Papal ceremonies, recognisable by their black attire and the badge with the motto ‘Preghiera, Azione, Sacrificio (Prayer Action Sacrifice). We collect the Peter’s Pence offering on June 29th at the four Vatican basilicas, which is then humbly presented to the Pope during the traditional annual audience reserved for the Circolo. The Popes have also supported the needy in Rome through Circolo San Pietro, allocating a sum annually for its charitable activities. There’s a night shelter, which costs €8 per night and is often covered by benefactors and donors; a food bank that distributes around 80,000 parcels to families and individuals in need; foster homes available to the less fortunate relatives of young patients at the Bambino Gesù Pediatric Hospital; a service that collects clothing; and a listening and assistance centre at the Basilica of San Giovanni Battista dei Fiorentini, where, during the upcoming Jubilee in 2025, pilgrims with disabilities will be welcomed and provided with a moment of comfort and respite: whether a change of clothes, a meal, or even just a drink.

All this is without forgetting the members providing care to terminally ill patients at the Sacro Cuore Hospice and the volunteers at the Bambino Gesù Pediatric Hospital, working in the wards or at the small shop that welcomes families in need. There is also a commission dedicated to worship, which is responsible, among other things, for organising a Mass held every Sunday morning inside the Colosseum, in a small chapel dedicated to Santa Maria della Pietà. A duty dating back to 1936. “For I was hungry, and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty, and you gave me something to drink; I was a stranger, and you welcomed me into your home”. At 37 Via Mastro Giorgio, this passage from the Gospel of Matthew is renewed daily, along with the joy that comes from giving to others. Just ask Maria, who has been working at this Testaccio kitchen for twenty-five years. When asked: “Are you happy to be here?” she answers yes, and the look in her eyes leaves no room for doubt.