“On earth, there’s church and there’s prison. If you go to church, you go to heaven. If you go to prison, you go to hell.”

For Bianca Dolce Miele

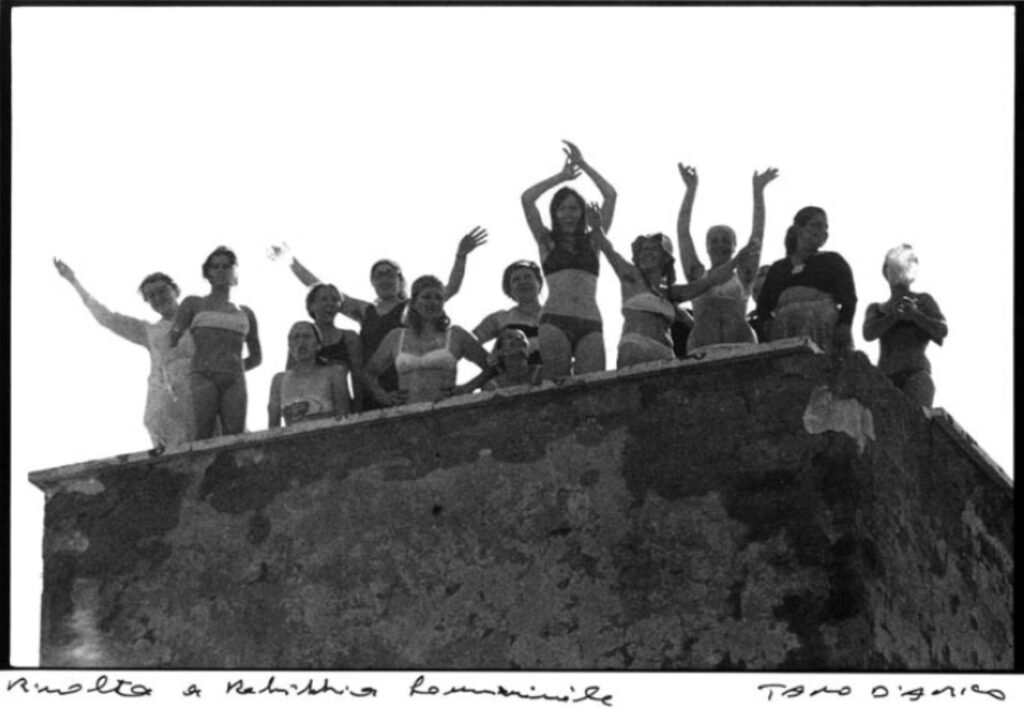

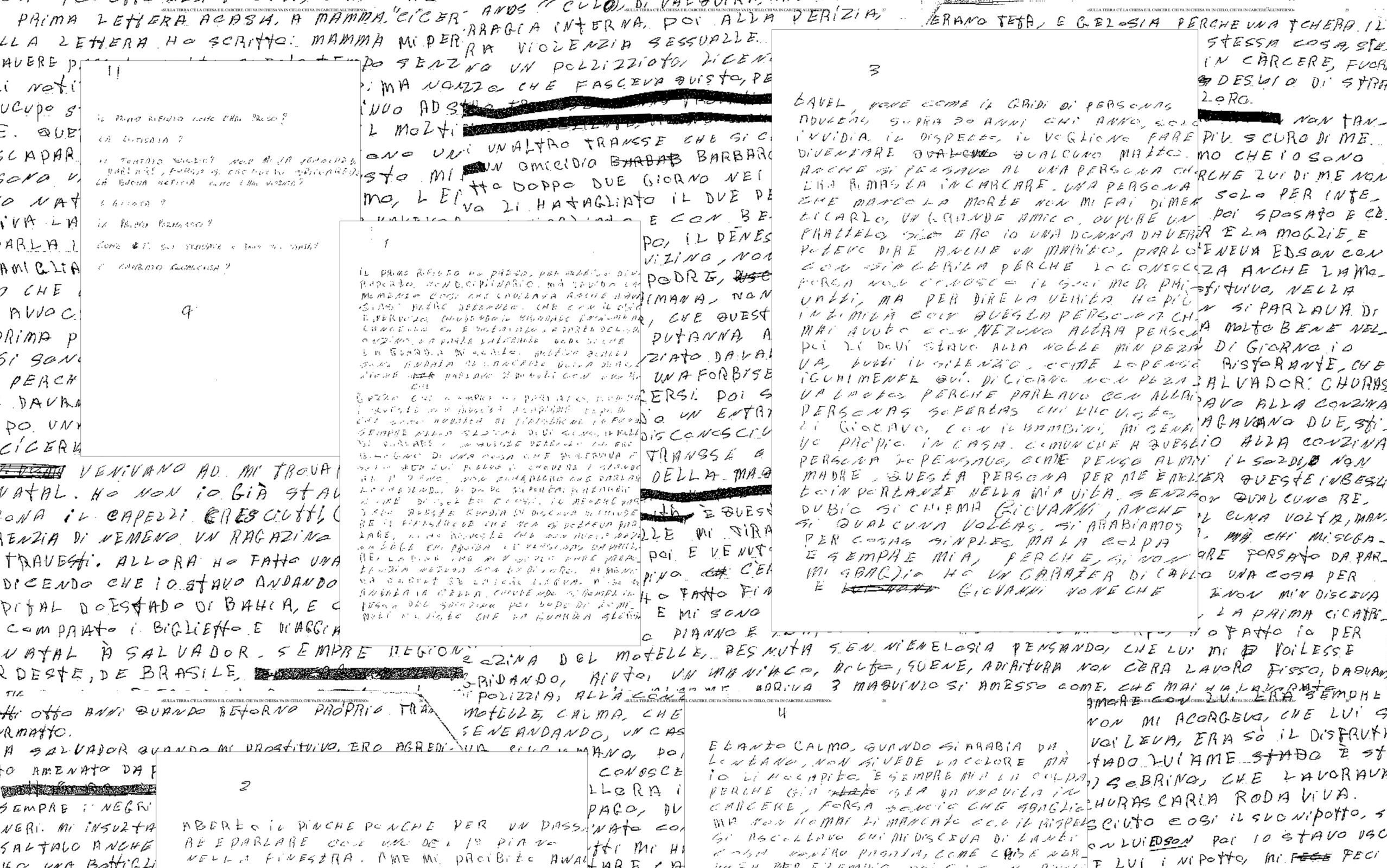

“On earth, there’s church and there’s prison. If you go to church, you go to heaven. If you go to prison, you go to hell.”[1] In this antechamber of hell that is Rebibbia prison, three stories crossed paths in the early Nineties. First, that of Fernanda Farias de Albuquerque, born in 1963, who arrived in Italy with the first wave of Brazilian trans sex workers and ended up in prison for the attempted murder of a boarding-house owner who had robbed her. Then that of Giovanni Tamponi, a Sardinian shepherd sentenced to life imprisonment at just 20 for a robbery-turned-homicide, and the first to take an interest in Fernanda’s case and record her testimony. And finally, that of Maurizio Jannelli, born in 1952, a member of the Roman column of the Red Brigades. Imprisoned since 1980, he transformed the testimony recorded by Giovanni into a novel, published in 1994 by Sensibili alle foglie, the publishing house founded inside Rebibbia itself by Renato Curcio and other former militants.

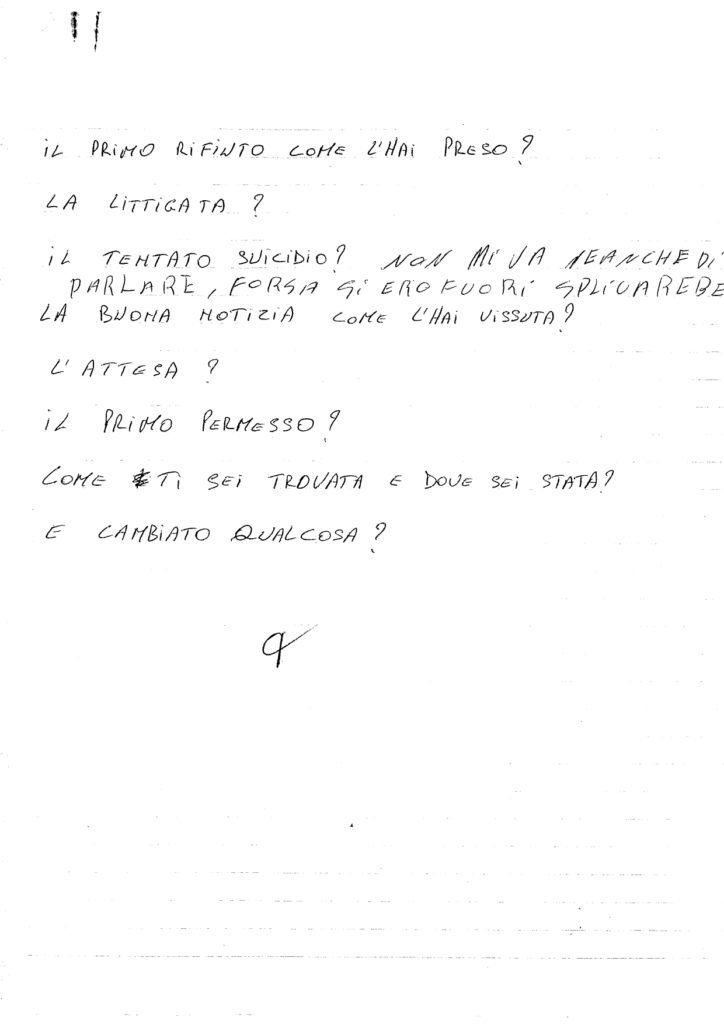

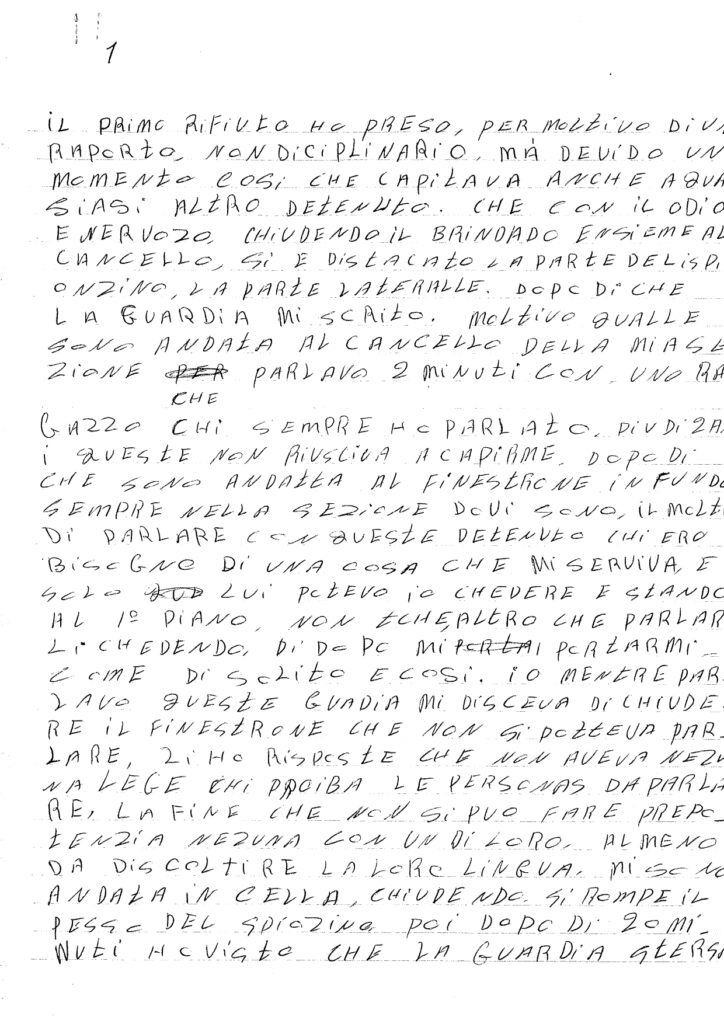

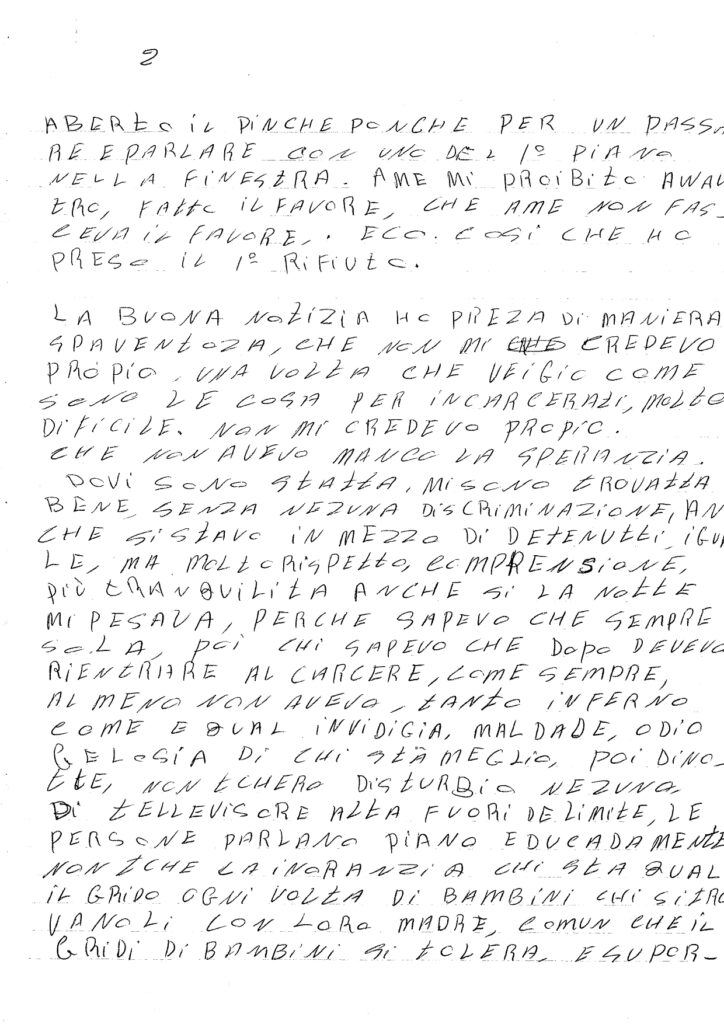

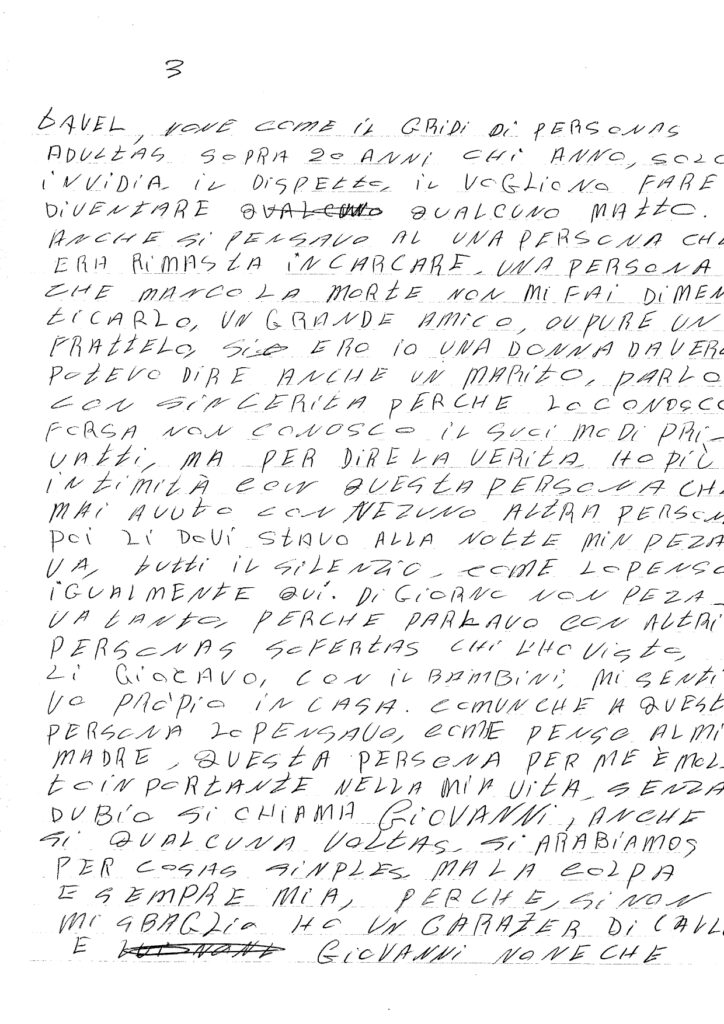

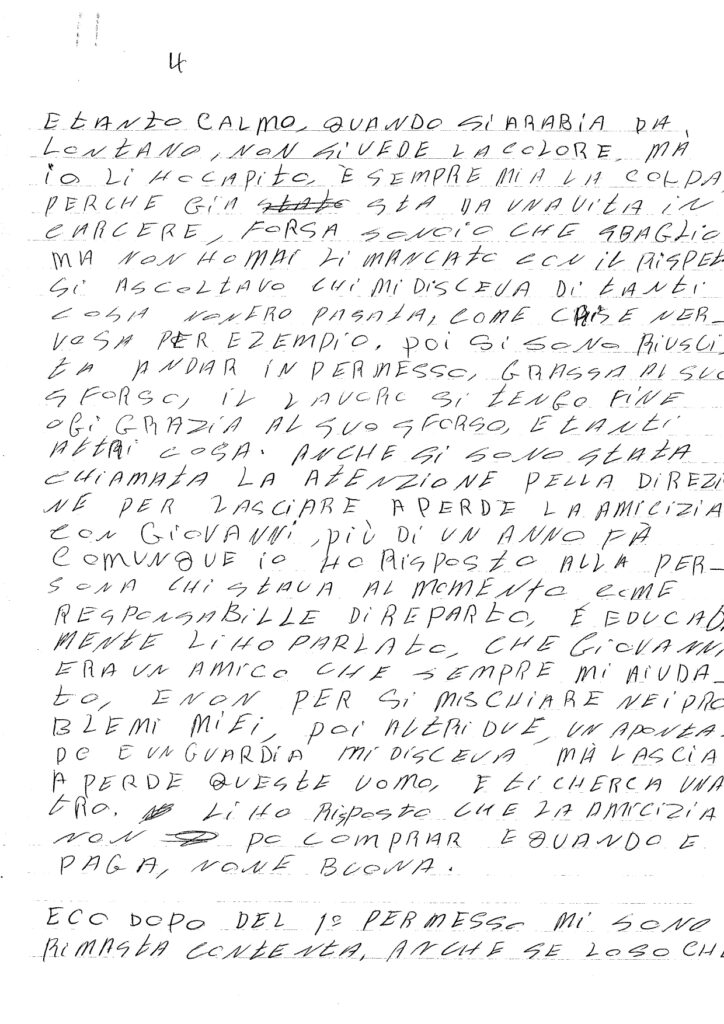

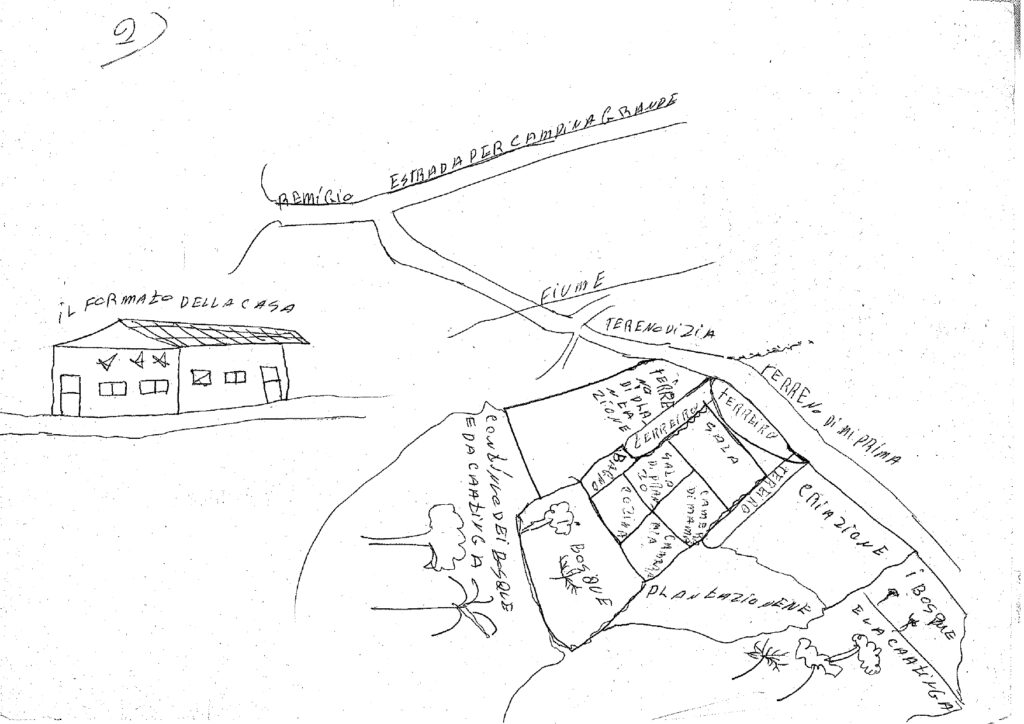

It was prison that made the encounter between these lives possible, through a clandestine exchange of letters. For Fernanda, what she shared with Giovanni was life-saving. In a hybrid language blending Italian, Sardinian, and Portuguese, she remembered him as “a very serious boy [who] helped with clothes, food, and also conversation [...] a person like that is very hard to find”. When they met, Giovanni had already been inside for fifteen years, because of “a fraction of a second in which I went from being a boy to being an adult”: the moment when, on his way out of a bank after a robbery, he fired. His mentality “wasn’t that of, say, a student”, but of “a farming and pastoral background, where you watched westerns on television, and it looked like you could walk into a bank, take the money, and walk out again. I’ve never claimed to be innocent. I did it, I was wrong, full stop”, he tells me. There is a kind of pride—a disenchanted sobriety—in the way Giovanni talks about himself, a tone that echoes the way Fernanda recounted her own life, marked by poverty, heroin addiction, suicide attempts, HIV, police violence, and abuse since childhood. Her tone never hints at self-pity, except in recalling her first moments in prison: “there sitting in front of three policemen with my head exploding with agony I never stopped crying”[2]. “Here is the story of the most tragic period of my life”[3], she said of the two years of imprisonment she had endured up to that point. Yet there is no trace of prison in the famous song that Fabrizio De André drew from the book Princesa, nor in the novel itself, which Maurizio describes as “the autobiography of someone else”. Prison was what they shared, but perhaps for that very reason, Maurizio tells me, “it was the thing that interested me least”. What drew him in was everything outside his own experience, anything that could lead elsewhere, both as a metaphorical escape to a Brazil he had never known, and in the practical sense of representing, for all three, a chance to leave prison: “That text wasn’t the result of writing in isolation, I didn’t write it with the idea of producing a literary work, it was a project of freedom. Its purpose was to free Fernanda.”

“Today, people and sexual variation are accepted for what they are, whereas back then, and even for Fernanda, you were either a man or a woman”, Maurizio explains. It was encountering Fernanda’s experience that cracked his own binary conviction. Even then, Giovanni observed: “I used to live in a world of my own, far from the big city, from consumerism... now [trans people for me] are people like everyone else”[4], yet capable of unveiling the mystery of sexuality, which concerns us all. For male prisoners, encountering trans women in the Rebibbia wing forced them to confront attractions, repulsions, fears, and desires long ignored or repressed. The novel not only recounts but lingers on—and even embellishes—Fernanda’s sexual experiences, with an awed fascination that forces the reader to split into both protagonist and voyeur, observing from inside and outside the first mischievous childhood games, the romances, and the encounters with her clients.

But the interplay of identification and distinction at the heart of the book also operates on another level. What struck Maurizio most was the tenacious affirmation of identity that drove Fernanda, who was fully aware of what she wanted and in open conflict with a world determined to deny it to her. At the time, Red Brigades militants who had not repented or dissociated would give up all benefits rather than renounce their identity, Maurizio recalls. Fernanda’s life resonated with their desire to transform themselves without betraying their fidelity to who they were. Her story, like that of those who did not renounce the ideals that led them into political struggle, is a story of transition, but one marked by the stubborn insistence on becoming what one is. In this sense, the encounter between Fernanda and Maurizio recalls a phase in which solidarity between left-wing militants and queer subjectivities—seen in films like Another Country (Marek Kanievska, 1984) or Kiss of the Spider Woman (Héctor Babenco, 1985)—was, although conflictual at times, almost inevitable. But if in Babenco’s film, set in a South American prison, William Hurt’s character, an imprisoned gay man, is deeply transformed and drawn into the political commitment of his cellmate, the exchange between Fernanda and Maurizio is decidedly one-way: he records her story, while she absorbs nothing of the world of armed struggle. “I believe she was closed off, trapped in an egocentric mindset. She took up all the space; she had no curiosity at all about a world that would have welcomed her. She followed her desire, which took her elsewhere”, Maurizio says. Their encounter seems, in this light, to symbolise an epochal passing of the baton: from political struggle to identity struggles.

Their encounter seems, in this light, to symbolise an epochal passing of the baton: from political struggle to identity struggles.

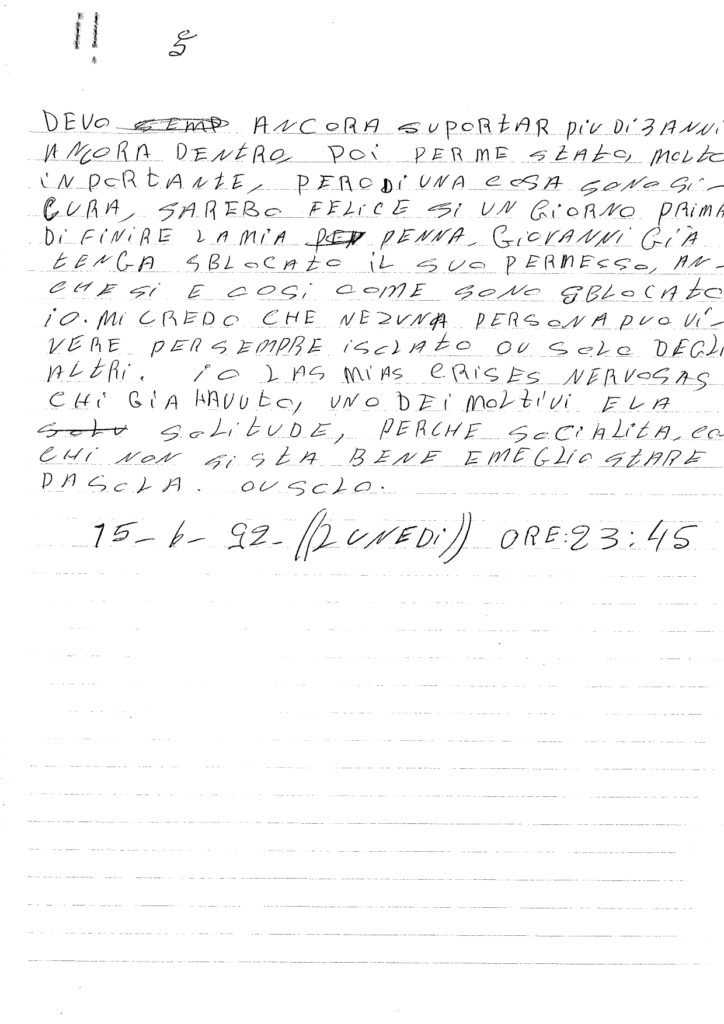

For Maurizio, the novel’s most profound merit remains that it helped secure Fernanda’s release. She began working for Sensibili alle foglie as a secretary, only to run away and return to the streets. “It was a good job, well paid. But I wanted those looks on me again”[5], she writes in the book of an old job in a restaurant kitchen in Bahia. In an interview, she later said with pride: “I started prostituting myself ten years ago. These things happen in the life of any ordinary woman. To depend on no one, to live my own way. Anyway, I like living like this. At night, everyone sees me.”[6] She lived torn between contradictions: the dream of being a wife and housewife on the one hand, the validation she gained through sex work on the other. What Fernanda sought, says Maurizio, was “a form of splendour, which can be glimpsed in the things she shared, and which is difficult to understand for those on the outside”. Fernanda died in Ancona in 2000, aged 37, in circumstances never clarified, possibly suicide. After this first experience as an author, Maurizio realised he wanted to continue telling stories, now through audiovisual work, and became a television and film director. He would often return to themes of prison and of trans prisoners. Giovanni has returned to Sardinia but remains under house arrest. Back in 1992, Fernanda wrote: “I feel very sorry to have Giovani in such a situation in prison. So long in prison, he has already paid too much. With his life. [...]I don’t know what ending up in prison solves for anyone because they have used a life.”[7]

More than thirty years have passed, and Rebibbia prison is still there. The paths of Fernanda, Giovanni, and Maurizio, however, have diverged—just as the alliances between groups in struggle seem to have fractured, for varied reasons yet perhaps not so different from those that once brought them together against the established order.

[1] Fernanda Farias de Albuquerque e Maurizio Jannelli, Princesa, Roma:Sensibili alle foglie, 1994, pp. ?,?.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Giovanni Tamponi in Carlo Conversi, Princesa: incontri irregolari, RAI Storie vere, 1994.

[5] Farias de Albuquerque e Jannelli, Princesa.

[6] Fernanda Farias de Albuquerque “Intervista” in Farias de Albuquerque e Jannelli, Princesa.

[7] Fernanda Farias de Albuquerque e Maurizio Jannelli, Princesa. Sono venuta di molto lontano, unpublished, available at www.princesa20.it