The History of Gorge from Tokyo to the Mountains (and Back)

There is a non-genre of music called Gorge that has animated many nights in Tokyo’s underground nightclubs, but it has much more to do with the outdoors—mountain climbing, hiking, and spelunking—than with city life.

“Any music genre has its myths at the time of its birth. Take hip-hop, techno, house—they’re all coloured by various legends of dubious authenticity. I love that kind of mythology, and there’s no doubt it affects how people psychologically experience music. So I decided to create a myth, intentionally. It’s just a matter of whether it’s done on purpose or not. The line between myth and reality is blurry, and I think that’s exciting.”

These words are from Tokyo-based musician Toki Takumi, during one of the email exchanges we had in support of the writing of this article. He is now known artistically as Hanali, and is the originator of a non-genre of music called Gorge—one that has animated many a night in Tokyo’s underground nightclubs, but also has, at least in its original conception, much more to do with the outdoors, with mountain climbing, hiking and spelunking than with city life. A genre that, in the space of fifteen odd years, has come to include a huge number of releases, ramifications and even subgenres, yet has somehow managed to never really cross over into the West and also remained fairly underground in its native Japan.

The mythology he speaks of is one that, for a very long time, helped him refuse the role of genre originator and, in his very own words, avoid becoming repressive to other artists. He envisioned Gorge as more of an open-source project, one so extremely inclusive that it could even retroactively claim music and artists who never even heard the term. As Takumi himself explains it: “Musical genres tend to be open source in nature, they often feel halfway there. (…) So I decided to create a fully open-source style of music by deliberately fabricating a myth, setting forth very simple rules (the ‘Gorge Public License’), and encouraging everyone to create. I wanted people to “hack” the genre known as Gorge. I was hoping it would evolve into a new “OS” for music, like Linux. As a result, I think this science fiction-like project was realised to some degree—in both quantity and quality—and it continues to operate.”

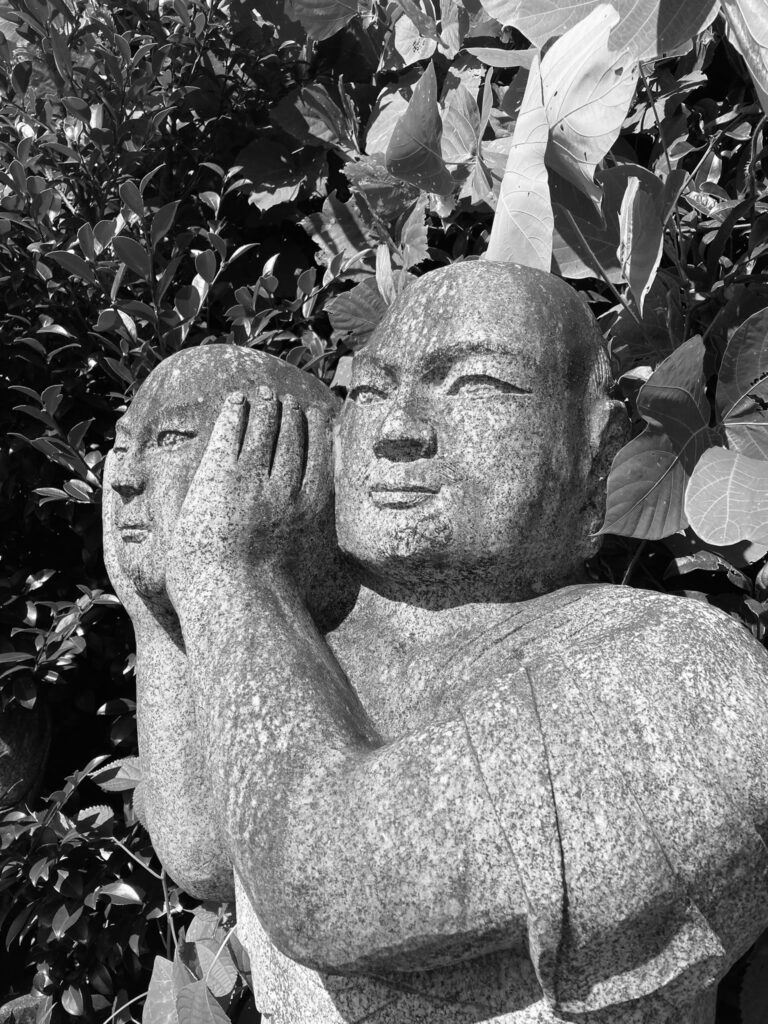

The Gorge Public License (or GPL) only counts three main rules: 1-Use toms. 2-Say it Gorge. 3-Don’t say it art. In the narrative fabricated and disseminated by Takumi, Gorge had actually been formulated by a mysterious figure named DJ Nanga, a homeless Tibetan mountaineer and part-time music selector who had often been playing it at Sherpa Club, a venue located, according to the legend, at the bottom of the Himalayas. As mentioned in the only (fake) interview DJ Nanga ever gave for Gorge.in (Takumi’s label), he had been given a cheap, barely functioning drum machine whose kick drum pad wasn’t functioning. This forced him to compensate by focusing on the toms, constructing rhythms that had very little in common with any already established genre.

And that’s what Gorge is: hard to define but somehow recognisable, its many manifestations united by a phantom thread of intricate percussion patterns, in open defiance of the most common tropes of Western dance music. In a world in which electronic genres are determined by specific rhythmic structures and BPMs, and often also by the memetic reproduction of specific samples, Gorge offered the freedom to use any tempo, any mood and any structure. Just follow DJ Nanga’s three main rules and you’ll be a Gorge artist, or rather, a “bootist”.

According to the myth, Gorge had been formulated by a mysterious figure named DJ Nanga, a homeless Tibetan mountaineer and part-time music selector.

This isn’t to say Gorge tracks have nothing in common: clearly influenced by the massive taiko percussions played at traditional festivals and by the type of drumming that accompanies noh and kabuki theatre, the jittering, relentless and often polyrhythmic beats of Gorge are in most cases accompanied by intense drones, distortion, and apparent chaos. Yusuke Kimura, one of the Gorge prime movers under the name Drastik Adhesive Force, openly recognises this influence: “We’ve been familiar with the sound of the taiko drums we heard at festivals since we were children. It feels amazing to hear the sound of big taiko drums, you can really feel the impact in your body.” It goes without saying that even the mention of “toms” in the GPU is open to subjective interpretation, as the percussive sounds used in the genre rarely sound exactly like regular tom-toms.

It is, in fact, more of a matter of structure. According to Takumi, attempting to create this kind of beat initially “Felt like exploring non-Euclidean geometry. Not a world of rhythm-bass-harmony, or kick-snare-bass, but a world of tom-tom-tom. I imagined a kind of science fiction in which gravity itself is based on tom drums. Then I’d wonder: ‘What music would I create in that world? What would other people create?’ That was a huge point of curiosity for me.”

Also always present in Gorge is a kind of psychedelic playfulness and unpredictability that in most cases gives birth to a general atmosphere of intensive effort—an energy that comes from the idea of confronting the earth’s crust’s most intimidating formation: the mountain. That’s because it is while climbing the Yatsugatake in Nagano that Takumi, himself an avid mountaineer, fictitiously met Nanga, befriended him and obtained from him an equally mysterious CD. It was a compilation of music performed at Club Sherpa that, according to him, was Gorge.

This is, of course, a complete fabrication on Takumi’s part. To this day, the only two DJ Nanga tracks to ever surface were indeed produced by Takumi. As he himself puts it: “I was fascinated by ‘mythology’ and ‘structure’. Rather than seeing it as art, I approached it with an anthropologist’s mindset, somewhat like Lévi-Strauss. Another aspect is that I’m a software engineer, so I’m deeply interested in computer science. Two main questions guided my thinking: ‘How can dance music stand apart from the Western-based norms that define its usual structure?’ and ‘What happens if we apply an open-source model (like in software) to music?’ DJ Nanga has authority, but it’s an invented authority. So the bootists can’t be suppressed by any ‘original founder.’ That’s different from having no originator at all—sometimes that vacuum gets filled in a repressive way. In Gorge, there is a clearly defined originator, but that figure is explicitly fictional.”

The purely musical idea of Gorge had actually come to him after a pretty serious injury kept him from climbing, an activity that, at that point in his life, had replaced music as his main passion: “My focus shifted largely because of mountaineering. I loved music throughout my twenties, but starting at age 30, I got seriously into climbing, so much so that I lost time to make music. I was always in the mountains. One day, I got injured. When I returned to music, I saw a completely different world. Previously, I cared too much about how others would react to my sound. But after climbing, I felt more like ‘I want to climb whatever route I’m personally interested in. I want to craft the music I want to explore. Let’s figure out a strategy for that.’ That mindset gave birth to Gorge.” He called it Gorge because he wanted to evoke the image of a narrow passage between walls of rock, as if one were climbing towards the source of a mountain river.

The thick and powerful sound of the tom functioned for Takumi as a symbol for rock itself, the intensity of the tracks being but a musical transposition of what, for him, is the true nature of climbing: “I don’t have a spiritual view of mountaineering. I see it more physically. Climbing is a question of whether you can or cannot step onto a certain spot, which comes down to strength, physicality, gravity, and friction. In other words, it’s about whether the natural environment affords you a certain action. You could call it philosophical rather than spiritual. At the same time, the sheer fact that humans climb mountains at all—even risking their lives to do so—is a profound mystery. Maybe there’s something about it we haven’t yet uncovered. People often explain this away as ‘spiritual’, but I resist that label. It’s too easy an answer for something I see as a bigger enigma.”

Climbing is a question of whether you can or cannot step onto a certain spot—it’s about whether the natural environment affords you a certain action.

Right after having this epiphany, Takumi started experimenting with his own music, which in 2012 led to his first album as Hanali: the unequivocally titled Gorge Is Gorge, released through his own label Gorge.in, in which he followed the GPU quite to the letter, as every track title does, in fact, contain the word Gorge. In the meantime he had already started to recruit the first batch of Gorge bootists—the word itself being a substitute for “artist” since, as stated in the GPU, if you call it Gorge you are forbidden from calling it art. Some of them he was already in contact with, and some of them were already getting close to a sound that could be said to be Gorge: “I basically reached out to people I knew and asked them, ‘Just put toms in your music—if it has toms, it’s Gorge.’ The producers themselves started thinking, ‘Hey, maybe what I’m making is Gorge?’ They got on board, and the tracks started coming together.”

One of the first to answer the call was Kimura, who at the time was a straight-up techno producer and DJ and had become friends with Takumi by attending and performing at the same electronic music parties and events, especially in the famous Tokyo district of Shibuya, famous for being where most of the city’s nightclubs are located. “He explained the Gorge project to me at an izakaya in Shibuya. I remember everyone getting excited when he told us about the concept of Gorge and GPL. After that, I started working on my first Gorge track for the first release.”

Thus Drastik Adhesive Force became part of the initial core group that gave birth to the very first Gorge Out Tokyo compilation, released on Gorge. on the same day as Hanali’s debut. The “rocky” artwork of both releases left no doubt about the genre’s aesthetic roots. Judging by their own words though, this initial scene, composed of Hanali and DAF alongside other projects such as uccelli, CRZKNY, Gorge Clooney and others wasn’t exactly super-tight, as Kimura testifies “There are many bootists I've never met, and some bootists whose existence is questionable.”

Nonetheless, the scene did have social gatherings, and they mainly happened in Shibuya. Gorge parties started to pop up, also thanks to the contribution of eclectic DJs (or “Gorge One Pushers”) like HiBiKi MaMeShiBa and Dubstronica. The very first Gorge event was titled ‘Gorge I/O’ and took place in September 2012 at a venue called Sakuradai Pool, opened with a keynote lecture by Takumi himself and featuring most of the Gorge Out 2012 cast.

At that very same time, another music scene was burgeoning in the darkened basements of Shibuya and Shinjuku, and what it had in common with Gorge was a passion for busy rhythms and unusual (at the time) tempos. Juke/Footwork had arrived in Japan and set off a minor explosion in the country’s electronic underground, spawning legendary players like DJ Fulltono and Foodman and label like Omoide. Though technically a US export, it didn’t take long for Japanese Juke to become its own thing and, despite being much more popular than Gorge, the two scenes immediately became heavily intertwined.

The crossover led to unexpected results, like Footwork DJs and Gorge bootists playing the same parties and even some of the most prolific ones like CRZKNY being effortlessly fluent in both genres and even occasionally attempting to merge them. It also led to Hanali opening for Chicago legend Traxman the first time he visited Japan, in 2013, at Shibuya mainstay Daikanyama Unit. “I remember surprising an audience that was there for a totally different genre”, comments Takumi, satisfyingly reminiscing on the experience.

The timing, though, wasn’t really great for either scene: 2013 and 2014 saw the Japanese government starting to enforce the so-called “Fueiho” law, a post-war era set of norms which regulated which venues could allow dancing after midnight to a point that most of the city’s clubs weren’t permitted to operate as late-night dancing venues. Luckily, a true shelter for electronic dance music could be found in Shibuya’s “virtual club” / online music broadcaster DOMMUNE, founded and hosted by the legendary Naohiro Ukawa. The first Gorge takeover of the channel in 2013 led to the spreading of the genre in Tokyo and beyond, and to a multiplication of the number of active bootists. The channel was also host to regular “Juke vs. Gorge” soundclashes, in which both camps friendly battled to make their respective marks on the world. [Fueiho was eventually lifted in late 2015.]

As mentioned, this operation and its open-sourceness was as proactive as it was retroactive “One thing I like [about the freedom given by the GPU] is that there is so much music that sounds like Gorge music. We can connect to it and say that Gorge has been here forever” says Kazuki Koga, a former smalltown boy turned Shibuya dweller (though now based in Canada) and a crucial part of the second generation of Gorge. In fact, a Pinterest board assembled by another crucial second-wave Bootist, Indus Bonze, shows a range of influences that covers everything from Joy Division to the Awa Odori festival in Tokushima, from Sandwell District to Haruomi Hosomo. As for Takumi, he considers prominent Japanese experimentalists like Otomo Yoshihide and his Ground Zero ensemble, Ruins and Boredoms not just as influential to Gorge, but as part of the genre (because, again, “if you say it’s Gorge, it’s Gorge”).

A Pinterest board shows a range of influences covering everything from Joy Division to the Awa Odori festival in Tokushima, from Sandwell District to Haruomi Hosomo.

But, above all, there is one key influence mentioned by virtually every bootist, to the point that bootleg remixes of their work have been produced by Indus Bonze and other bootists: Japanese anime’s most crucial export, AKIRA, and especially its marvellous soundtrack by ensemble Geinoh Yamashirogumi. When asked about his love for their music, Kimura says: “I love both the AKIRA manga and anime. I go to Geinoh Yamashirogumi concerts every year. They are currently performing Jegog, an Indonesian percussion instrument, with a new interpretation, and it’s wonderful. However, we only rediscovered Geinoh Yamashirogumi after we started Gorge. While searching for past music with the Gorge interpretation, we remembered Geinoh Yamashirogumi.”

In fact, nothing could be more prophetic than AKIRA itself, a science fiction story set in 2010s Tokyo and set to a pan-Asian-fusion soundtrack of predominantly drums and electronics. At the end of the original manga, the landscape of a newly re-destroyed Tokyo and its piled ruins looks more like a concrete mountain range than a city, as the protagonists ultimately lay claim to it, with the aim of creating a new community and a new, self-organised community. Conquering a hostile, verticalised environment in the name of freedom. It doesn’t really get any more Gorge than that.

Other manga and anime had an impact on the scene, both musically and conceptually: Kenji Kawai’s score for 1995’s Ghost In The Shell is another favourite, and in 2016 Hanali was asked by mangaka Q Hayashida and Japanese webzine GHz to participate in a soundtrack project for her breakthrough manga Dorohedoro. He provided a track and crafted a “Hole”-themed Gorge mix to promote it. Of great importance was also Jiro Taniguchi’s magnum opus The Summit Of The Gods, the intense existentialist tale of a man’s attempt to climb Mount Everest by himself. Takumi cites it as his favourite manga, while Kazuki Koga even named an album after it.

As for his involvement in Gorge, Koga’s story goes like this: “Literally after watching the first DOMMUNE program I made a song called ‘Climbing For Gorge’ and uploaded it on Soundcloud. I have now deleted it, but at the time it was reposted by all the Gorge fans who wanted to promote this new guy. So I said to myself ‘This is amazing, I can now start my career as a Gorge bootist’. I also started bouldering, because I wanted to understand the spirituality and aesthetic of climbing.”

And it wasn’t just him: from that moment on Gorge solidified its presence in both the Shibuya nightlife (at venues like OTO and Forestlimit) and Japanese music in general, spreading to other regions like Sapporo, Fukuoka and Nagoya. In Okinawa, one producer named Tea-Chi decided to create his own brand of Gorge, blending it with local folk music and naming it “Island Gorge”. When asked how club audiences react to Gorge, Takumi’s reply shouldn’t, at this point, surprise anyone: “It can vary wildly—people might dance like crazy, or they might just stand there, not sure what they’re hearing. All of that is part of Gorge. Sometimes they come to speak to me after my sets and tell me they felt like they climbed a mountain.”

People might dance like crazy, or they might just stand there, not sure what they’re hearing. All of that is part of Gorge.

What it sadly wasn’t really able to do was to firmly set foot into the West. No media, festival or institution in experimental electronic music has so far expressed enough interest in the genre, apart from a few sporadic examples. Some foreign micro scenes or solo artists did pop up, and to some very interesting results, but they didn’t seem really gain too much traction: like the group of US bootists gathered by part-time Boredoms drummer San Gabriel, the meditative, quasi-ambient version of Gorge produced by the Pantanosumpf collective in Argentina, or the incredible Maori version of Gorge envisioned by New Zealander bootist Hasji.

When asked why they think that is, every bootist I’ve spoken to cites language barriers, with Kimura adding: “It may not have reached because it's a small scene in Japan. Everyone, including myself, is doing musical activities within their daily lives. It's purely a hobby. Touring Europe and the United States is not very realistic.” Takumi seems unbothered by it: “Achieving ‘global success’ wasn’t really a big priority for me. I’m fine with it just existing as it is. If it spreads around the world in a hundred years or a thousand years, that would be exciting. I like thinking on a time scale where the seafloor might rise up and become a mountain. Whether or not it happens in my lifetime isn’t my main concern.” Still, to fans of the genre, it feels a bit weird to see that, those few times when some bootist manages to get released on a more prominent label, like when T5UMUT5UMU did an evidently Gorge EP on Hakuna Kulala, the word Gorge isn’t mentioned at all, not even as a tag on Bandcamp.

Still, slowly and steadily, the Gorge scene seems to keep on living and growing, even though much has changed since day one. Some bootists have created their own subgenres, like Drastik Adhesive Force’s SLAB, marked by low BPMs and metallic sounds, on which Kimura has to say: “It’s about pursuing music that you can dance wildly to even at a slow tempo. Slab is a climbing term that means a gently sloping, flat rock. Hanali named it, feeling that the way I slowly move forward on a powerful, flat rock is similar to my music.” Koga, on his part, decided to push the envelope on cinematic sound design and digital deconstruction, while still keeping his tracks raw and powerful.

Others have joined the scene only partially and tangentially, like Naoki Takano, who produces music as In The Sun and promotes an ongoing series of experimental music events known as RAW TEMPO, who told me: “I first learned about Gorge when an audience member at an In The Sun live show told me that our music sounded like Gorge. Before that, I wasn’t very familiar with it. Even now, I don’t consider myself a part of it, but I do like the Gorge scene.” Many other proper bootists, instead, like the previously mentioned Indus Bonze, T5UMUT5UMU and CRZKNY have decided to contaminate their Gorge with other highly percussive genres coming from other parts of the world, like Tanzanian Singeli, South African GQOM, jungle, gabber and even hardgroove. This seems to be the main thread also followed by many younger artists in the Japanese electronic scene, like KΣITO, WRACK or DJ MORO, who—although clearly influenced by the previous generation—seem more intent on creating their own versions of sonic ideas coming from abroad. Either way, Gorge music is still played and bootists do guest at parties like Goru Goru Fridays at OTO, and Gorge.in still holds his big annual gathering on the national holiday of Mountain Day (August 11).

When asked what, in their opinion, the future holds for Gorge, the two older bootists I spoke with, unsurprisingly, gave very similar responses. First Kimura: “The number of new bootists is gradually increasing, so if it continues for another 100 years or so, it might become mainstream.” Takumi’s focus is set even further in time: “Compared to the time it takes for mountains to form, everything that’s happened with Gorge so far is just a tiny grain of sand. I’m sure we’ll see even more interesting developments. It would be amazing if alien life forms rediscovered Gorge a million years from now.”

After this, I’d say, there is very little to add. Keep climbing and long live Gorge!