“It sounds like this Shakespeare lived in the streets of my city.”

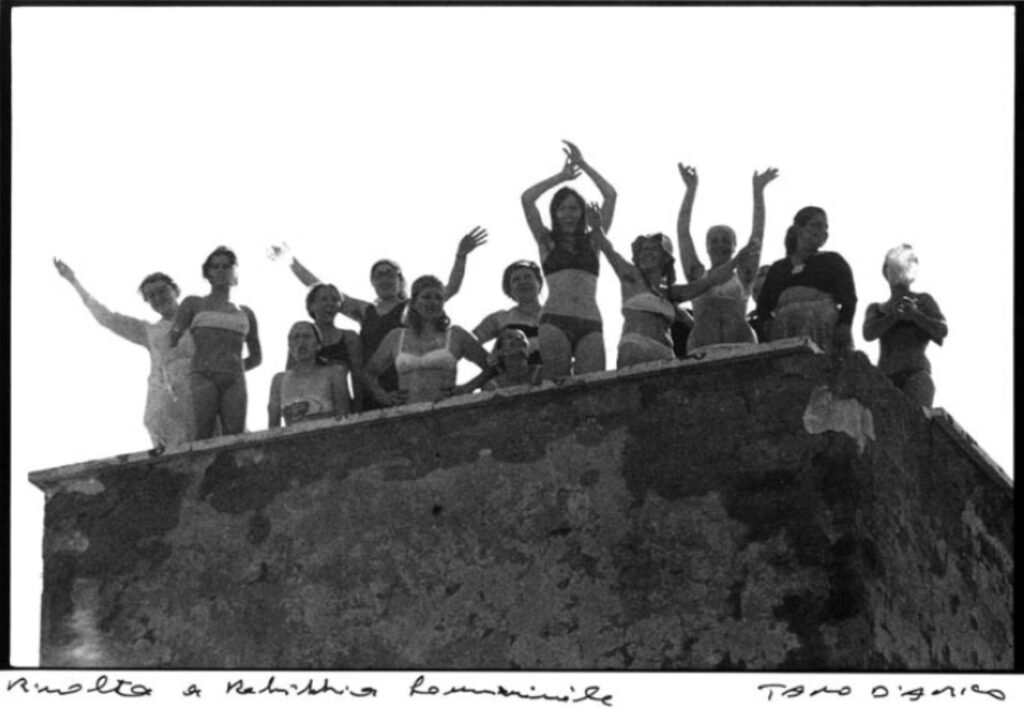

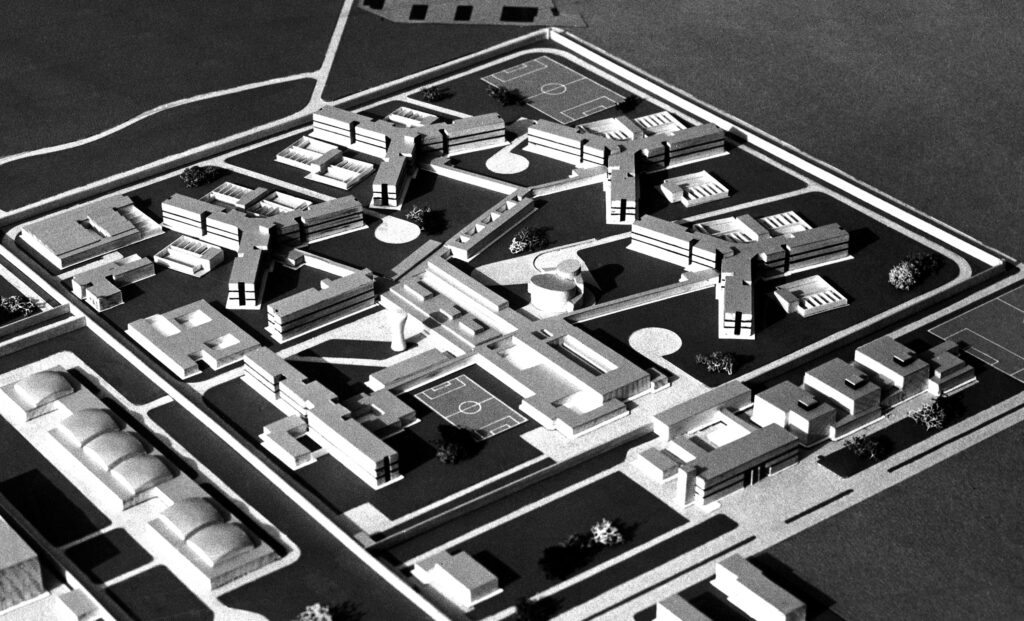

Along a narrow outdoor corridor enclosed by iron grates, a group of men advances, led by an imposing figure. They move into a side area hemmed in by high walls and topped with mesh through which a sliver of sky is visible. It is here that Caesar is killed. And it is here, before the Roman general’s still-warm body, that Antony addresses the conspirators, while from a nearby watchtower two prison guards become engrossed in the scene and ask a third, more rule-bound colleague to wait a few minutes before sending the inmates back to their cells (“Let them finish the scene”). It is one of the pivotal moments in Caesar Must Die, the 2012 film that opened Rebibbia prison to the gaze of the world. This is not a figure of speech. The docufiction portraying the work of the prison’s theatre group—winner of a Golden Bear and a David di Donatello for the Taviani brothers who directed it, among many other awards—is filmed entirely inside Rome’s largest penal institution: in the theatre, where the ensemble of inmate actors led by director Fabio Cavalli stages its productions; in the cells, where character and incarcerated person blur as they commit the text to memory; in the outdoor yards, the library, the corridors, and even at the entrance forecourt, where the massive steel gates separate the prison from the outside world. Through cinema, all these places suddenly became visible beyond the walls. And it sharply heightened national awareness of what artistic work can mean inside penitentiary institutions, with important examples from Rome to Volterra, Milan to Modena.

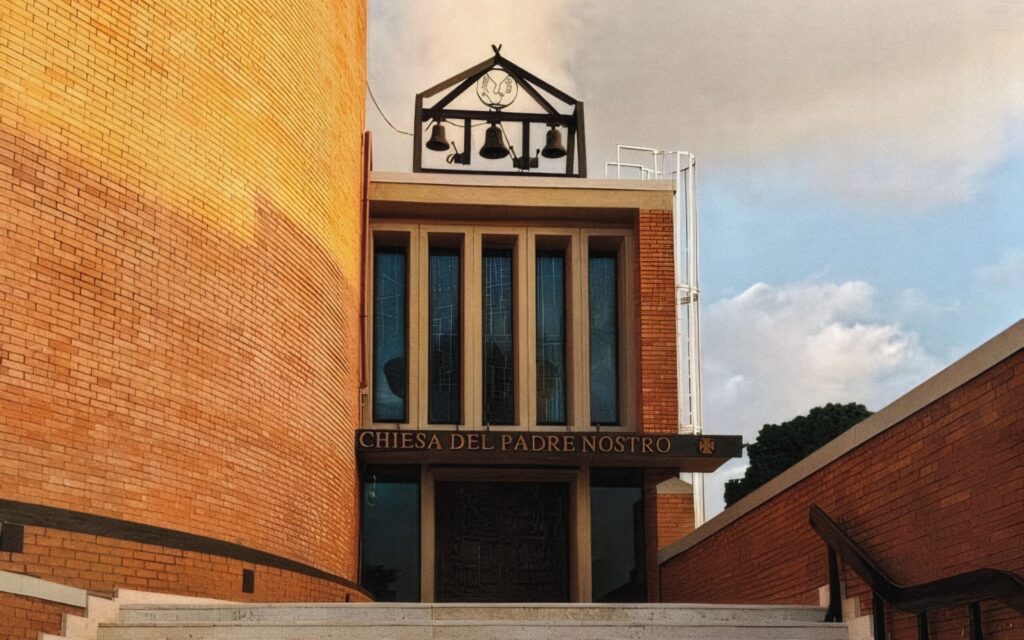

I first stepped through the prison’s imposing entrance more than twenty years ago to collaborate with the Arci La Rondine cultural group, led by Cosimo Rega, who was then a high-security inmate. We were setting up a journalism workshop for people in his unit, teaching the basics of editorial work. While spending time with the group, I had a chance to watch rehearsals for a production they were creating with Fabio Cavalli: Eduardo De Filippo’s Napoli milionaria. “I first arrived in Rebibbia in 2003 with Isabella Quarantotti De Filippo, Eduardo’s widow, who had met Cosimo and become deeply invested in this cultural and social project”, Fabio recalls. The group he encountered consisted entirely of high-security inmates, imprisoned under Article 416-bis for organised crime offences. People who had never taken part in a theatre project before and yet undertook a journey of artistic and personal development that began with that first experience. “I remember that at the start they proposed we repeat Eduardo’s televised version scene by scene. They had a videotape they watched on a TV installed inside a metal box with bars across the screen. Even the TV picture appeared through a grid in those days. Their idea of theatre came from pure imitation. Yet, that afternoon, faced with such a simple way of doing theatre, I saw more theatre than I had ever seen before.” The production opened in 2004 and was a success, encouraging the ensemble to continue.

For the next play, the director proposed a new idea. He sought permission from Eduardo’s family to use the Neapolitan translation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which Eduardo had completed for Einaudi in 1984. At first, there was deep hesitation. The actors were almost all from southern Italy, steeped in Eduardo’s work. Performing anything else felt like too great a leap. “It took an intervention from Luca De Filippo, who came to the theatre and told the actors: Eduardo is immense, he is the sun, but Shakespeare is the universe”, says Fabio. Shakespeare, the greatest playwright of all time, was unfamiliar to most of them. But once their doubts subsided, the production flourished and surpassed the success of Napoli milionaria. From then on, the company’s work became widely known.

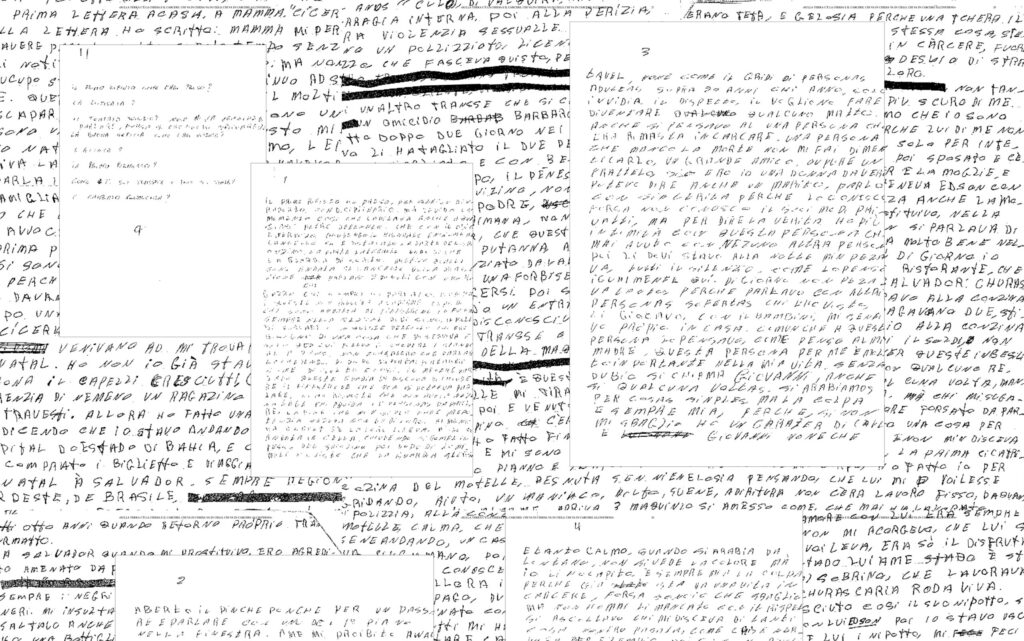

To highlight the actors’ expressive power, dialect was used. With Eduardo, this was inherent to the dramaturgy; in Caesar Must Die, Neapolitan, Romanesco, and Sicilian inflections are heard. In one scene, Cavalli urges Giovanni Arcuri, who plays Caesar, to use a Romanesco that is neither coarse nor affected—the right register to preserve both the authenticity of the actor’s own voice and the character’s solemnity. Cavalli recalls that assembling the right cast for the film was not easy. It is no coincidence that the auditions earned a dedicated scene in the film, which ends with the actors’ faces shown one by one, their sentences superimposed. Given that Caesar exits the play halfway through, the true protagonists of Shakespeare’s text are Brutus and Cassius: Brutus is played by Salvatore Striano, who had already left prison and found success in Matteo Garrone’s Gomorrah and other films; Cassius is played by Cosimo Rega in an unforgettable performance.

Conspiracy, betrayal, guilt, leadership, and the corruption of power—all central themes in Shakespeare’s tragedy—echoed the actors’ own lives and the paths that had led them to prison.

Cosimo Rega played a crucial role both on and off stage, effectively acting as the capocomico: the person who inspires the group, keeps morale high, and drives the work forward. This is how Fabio remembers him: “Cosimo was not an educated man, but he had great sensitivity and strategic intelligence. He redirected that strategic ability—once used for criminal ends—towards art. He transformed himself from within. I believe a key moment of that transformation was his encounter with Prospero. At the end of The Tempest, Prospero breaks his magic staff, the tool used to weave deceptions and exact revenge. It is almost as though he were laying down a gun. He becomes human again, shedding the robes of the magician to stand among men. Cosimo underwent this same process and, over the years, gained the trust of those inside with him, of us on the outside, and of the institutions. So much so that he managed to leave prison despite having been sentenced to life without parole. He died not long after, sadly, but he died free.”

Other actors have taken on that capocomico role over time. It remains essential, because even when the director is absent, the life of the ensemble continues inside the prison, as do rehearsals. Someone must serve as the group’s heart, the person who builds and holds it together.

The idea to do Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar came from the Taviani brothers. They had seen the Rebibbia ensemble at work and were convinced of its cinematic potential but needed a story with universal resonance. Conspiracy, betrayal, guilt, leadership, and the corruption of power—all central themes in Shakespeare’s tragedy—echoed the actors’ own lives and the paths that had led them to prison. “Sorry Fabio”, Cosimo Rega says at one point, turning to the director because he can no longer continue the scene, “but it sounds like this Shakespeare lived in the streets of my city.”

The film was released to major acclaim, aided by several supporters, including Nanni Moretti, who took charge of distribution at a time when few believed in the project. Today, it remains not only a stark, intense film and a document of what theatre-making inside prison entails, but also a striking portrait of the prison itself, seen in a completely new light. The high-angle shots, the corridors, the powerful ensemble scene in which the people of Rome appear behind barred windows, alternately applauding and responding to Mark Antony’s speech—delivered by Antonio Frasca—are all images of extraordinary evocative force, revealing a place transformed by art. The authority of the Taviani brothers, the trust in Cavalli’s work, and the conviction of Rebibbia’s then director, Carmelo Cantone, made it possible to create a film that is both a portrait of the prison and a work of transfiguration. “But shooting and working with cameras wasn’t always easy inside. You can’t start at seven in the morning and finish at ten at night, as you sometimes do on set. You have to conform to the prison timetable”, Fabio explains. “Everybody was tremendously collaborative, but bureaucracy can still get in the way. Even with theatre work, there were times when someone was transferred for various reasons, such as overcrowding, leaving us with only half a company. The administration always stepped in quickly to remedy these situations, usually caused by oversight, because there is an agreement stating that anyone attending university or doing theatre cannot be transferred, as continuity is essential.”

Prison theatre changes life during and after incarceration. Not only because, as all statistics show, recidivism dramatically decreases among those involved in such activities, but also because theatre often triggers a genuine, lasting transformation.

Juan Dario Bonetti, who plays Decius in the film, is now out of prison and combines his regular job with acting for the ex-inmates’ theatre company from Rebibbia, still directed by Fabio Cavalli. Like many others, he has not left the stage and continues to perform in new projects. “Working with the Taviani brothers was extraordinary”, he says, “partly because we didn’t fully grasp what we were part of. We watched these two elderly men filming, editing, and only at the end did we understand the extent of their ability to find poetry even there, among the cells. The film was a huge success. Some of us were able to follow its journey closely and enjoy it; others, like me, could not, because we were still inside and unable to leave. But that’s okay. Today, prisons seem much more closed than they used to be, and it is much harder to get projects like that off the ground. For me, it was an incredible experience, and I believe it was possible because everyone played their part—the institutions, us, the directors.”

Bonetti recalls that, like many others, he started doing theatre simply to pass the time, perhaps for a bit of fun. But then he realised that, through theatre, time in prison could acquire meaning. “And giving meaning to time, in prison, is the best possible thing you can do.”