Inside Out

These are the stories of Rebibbia. The stories of 17 people—a small group who resemble, however, the many who inhabit all these countries where you end up without ever wanting to.

Prison is a country most people never come to know. You don’t set out for it; you end up there, often without quite realising how. No one chooses it. Only those who work inside—those who recognise the need, and sometimes the vocation, to stand alongside the people who live in this place—can claim anything like choice. And even they are perhaps not entirely certain. Many, across history, have entered this world out of sheer necessity. And necessity, too, is the reason the story of this country must be told from within: from its rooms, its windows, its yards. In the country of incarceration, the universe splits and turns in on itself. A before becomes an after, and an after becomes a before; an outside becomes an inside, an inside an outside. The world flips upside down: everything is where it should be, yet everything follows different rules. Mohamed is a footballer outside and a footballer inside, wanting nothing more than to play, yet the pitch and the game are something else entirely here. Stefano knows spirits, the ones outside and the ones inside, but the spirits of the cells are different again, and here he has learnt he prefers the ones he once glimpsed among the flowers. Ezio carries a beast within him, outside and inside, and in here the beast is restrained not by bars but by a rosary. Alessandro writes about the sociology of prisons from the inside, as an inmate, making him the only person to whom inmates tell the truth. There is Antonio, who knows he will have to relearn engines when all cars turn electric in a few years, and Massimiliano, who says what everyone here knows: “If you can’t get through things, you can’t say you’ve lived.” In here, as Stefano reminds us, you have to get through your dreams as well. Dreaming is dangerous: it pulls you towards hope, tricking you into imagining a freedom that is precisely what you are denied. Below becomes above, outside becomes inside. So how do those who inhabit this upside-down country see the inside and the outside? And how do those who come in from the outside see them?

Piergiorgio Caserini

Alessandro

In conversation with Giulio Pecci

I’m a free person. I’m on a journey, the journey of my life, I’m just living it in a parallel world: prison. My day is split into three parts: prayer, which trains my spirit and soul; study, which trains my mind; and sport, which trains my body. I am trying to reach perfect psycho-physical and spiritual form, given that I have to get through each day as happily as I can.

I was a university student on the outside and, coming from politics—I was a Christian Democracy activist—the obvious choice was law. But I didn’t like it, so I tried psychology, then picked up my studies again in prison, this time with sociology. That’s when I realised I was a sociologist. I always had been. On my travels, I was always searching for something. I felt there was something I needed to discover, though I had no idea what. I’d leave, meet people, learn their customs and habits. To stay on the road as much as possible, I supported myself as a dancer, a club dancer, a waiter… whatever I had to do!

I won my PhD place from inside prison. Everyone said, “Why are you even applying? You only get in if you’ve got connections.” I didn’t give a damn. I sat the public exam and passed. What does that show? That nothing is easy, nobody gives you anything, and suffering and effort are the same for everyone. That studying inside is the same as studying outside.

I write by hand, at night, with my eyes closed because, you know, our synapses activate while we sleep. It’s the subconscious doing the work, our personal database putting everything in order. That’s why ideas come at night. I keep a stool next to my bed with a notebook and a pen on it, and as I drift off, I start writing whatever comes to mind. Then the next day, I rewrite it neatly. That’s how I wrote three books on prison, as a sociologist. And you know what my source is? The inmates. They tell you the truth. Well, they tell it to me, because I’m an inmate like them. They won’t tell you.

You need to understand something important: three innocent people go to prison in Italy every day. That’s a statistical fact, which means that on average 1,095 people a year are ripped away from their families, torn from their loved ones, dragged through the media like they’re violent criminals—and no one even bothers to apologise when they get out. The awful thing is that this number comes from the Court of Auditors, which handles the compensation claims. So those three a day are only the ones who actually get compensated. I’m saying this because it’s the innocent ones who never get anything. The innocent person is condemned to die in prison because they can’t ask for anything, while the proven guilty can ask, and get given. Even people with life sentences get out. There’s a clear disparity in treatment, and that’s what I’m fighting.

In a way, my situation mirrors Nelson Mandela’s. But let’s be clear: Mandela had a moral and political responsibility for what the African National Congress did—the attacks and everything else. Twenty-seven years inside pursuing an ideal, and he ends up winning the Nobel Prize. I never had that kind of responsibility. I’m innocent and I’ve always said so. I came in at twenty-three; now I’m fifty-three. For the first twenty-seven years, I looked at Mandela’s face every day. After that, the only face I’ve looked at is my own. I look in the mirror, do my hair, and say: “Come on, Ale. Let’s go.” I’m certainly not going to win the Nobel Peace Prize, I’m not going to be made President of the Italian Republic, but I do hope one day to read the words: “Life sentences no longer exist in Italy.” I’ve been in prison for thirty years, but it still feels like yesterday: time and space don’t exist.

You can be the puppet, or you can be the honest puppeteer.

They’re just conventions we made up; who says a year has to be made of that many days? To me, prison—and I’m speaking as a sociologist—could genuinely be a place where guilty people have the chance at an opportunity: learn a trade, discover their talents, make use of them, and give themselves a chance to change. But it all depends on politics, and politics is everything, inside and outside. Even the clothes you choose, the shoes you choose—it’s all politics. The great Aldo Moro used to tell young people: “Take an interest in politics, because if you don’t, politics will take an interest in you.” The choice is always the same: be a puppeteer, a puppet or, worse, a marionette. And you need to understand the difference between a puppet and a marionette: the puppet moves with strings, the marionette has a hand shoved up its arse. You can be the puppet, or you can be the honest puppeteer.

Let me give you another example. Lentini, the Sicilian town where I’m from, is the birthplace of Gorgias, one of the greatest sophists of all time—the father of rhetoric. Now, in sophist rhetoric, the most important thing is the word. The word wins over everything; truth doesn’t matter. So rhetoric is the art of convincing and persuading. Even though I grew up in Lentini, I always despised Gorgias and that way of thinking. There was a kind of rite of passage: there’s a statue of Gorgias in the municipal gardens, and anyone finishing the high school had to put a cigarette in his mouth and light it. I never lit that cigarette. A good orator, according to Aristotle and Plato, is someone who can communicate and persuade others who may not have their knowledge, while always pointing them towards a path of truth. That’s the difference, and I’ve always followed that line. And when you look in that direction, that’s where faith comes in. The thing that makes me say, “Keep going.” I’ll give you an example. Right now, I’m reading Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance, the current Vice President of the United States. It’s the American dream. Every inmate could learn something from Vance’s life. That guy grew up in a place nobody gets out of, you know? His story is the story of every kid from the hood.

Let me tell you a nice tale from when they put me in solitary for two years, three months, and twenty days. Since I couldn’t talk to anyone, I started talking to the crows. I’d go out alone to walk in a yard covered by a net like a giant aviary. One day, I heard wings hitting the wire mesh: a crow was stuck. I asked the officer if I could free it because it was killing itself, like it would rather die than stay trapped. As soon as I went in, I saw its mate stop, go silent, and look at me with this solemn expression. When I tried to reassure the trapped bird, she let me pick her up and looked at me with these hopeful eyes. I untangled her, gave her a kiss, and threw her into the air: “Go on, girl, fly to freedom”, I said. From that moment on, every day, those two crows waited in the spot where I walked, and they cawed every time I brought them crumbs.

I think in that moment of crisis they imprinted on me. To pass the time, I’d caw my name at them—“Caw-caw-caw-caw, A-les-san-dro”—and they’d reply, syllable by syllable. They never abandoned me. When solitary ended, I didn’t see them again. But one day, at the time I used to go out for my walk, I heard the cawing of those two crows from my cell, and I called out the window. They perched nearby and started cawing my name, like they were asking what had happened to me. We spent a bit of time together; then I told them we wouldn’t see each other again in that yard. I said goodbye with the same mix of joy and sadness you feel when you say goodbye to a close friend who’s being released. After we repeated my name one last time together, I told them we’d meet again in another life. I haven’t seen or heard them since.

I’m sure sensitive people can understand the intensity of a relationship like that between different beings: a man and two birds who, each in their own way, felt the same despair. People call me crazy but call me whatever the hell you want! I’ve prayed with Muslims too. Each with his own ritual, his own way. What united us was always a merciful God. In the end, what matters: the way you pray or the prayer and the intention behind it? We prayed for peace, for the love of all peoples. Each one of these beautiful encounters matters. They help create what I call a “cultural forge”: a place to form a new kind of person, someone who will spread a new, integrated, multicultural culture. That term is mine. The idea is to create a third culture that incorporates the best of all cultures and religious traditions, so that the young person who grows up with it knows it exists thanks to contributions from Christians, Muslims, Jews. So they can’t see a Jew or a Muslim as the enemy, because that would mean seeing themselves as the enemy. That’s what these encounters inside prison are for.

If I ever manage to get out of here, I want to keep travelling. That’s my biggest dream. Travelling physically, moving around… Living a life of cultivating my inner freedom. You don’t need much to survive: three meals a day, a pair of comfy shoes, a pair of glasses because I can’t see well anymore, and a pen to write with. That’s enough.

Antonio

In conversation with Giulio Pecci

I’ve never committed a crime. Never stolen, never taken drugs, nothing. I’m a mechanic, always have been. I did 35 years at Mercedes, then opened my own workshop. One day, the carabinieri showed up for an inspection and found an Audi A6 engine of doubtful origin. They wrote me up, nothing major. I carried on with my life, kept working. They came back three more times, I got a few papers through, and I just kept working. I thought it was all nonsense. Then one morning at 7 am, ten years after that first inspection, the local marshal turned up. I knew him—small town, his wife even used to bring her car to me—so I asked if he wanted a coffee. But he had an arrest warrant. “You’re kidding, right?” I said. He wasn’t. My wife hit the floor, out cold.

Even the lawyer I hired when I got inside couldn’t believe the sentence. “If you’d defended yourself,” he said. But I’ve never had anything to do with lawyers. I thought it was all trivial stuff, so I never turned up for any hearings, never looked for a lawyer. You know how it all happened? A bloke came in asking to have the engine on his Audi changed. “I’ll sort the engine for you,” I told him, and I went to get one from a scrapyard. Since when do you ask where a piece from a scrapyard comes from? You barely ask for a receipt. For me, €1,500 of spare parts turned into fourteen years in prison. That’s how it went, and there’s nothing I can do about it. I’ve got to accept whatever comes. Even if prison isn’t really my world, I got used to it in the end. I adapt quickly.

And I’ve met good lads in here. You just need to learn how to pass the time. Especially someone like me, who can’t sit about doing nothing. I’ve always loved drawing, so I draw. It runs in the family—my daughter’s a tattoo artist. I’ve even started doing theatre, which I now take seriously, almost like a job, and I sang in the choir for Pope Francis. But being a mechanic is my real trade. I devoted my life to it, and I’d like to go back to it once I’m out. Even if by the time I’m released, it’ll all be electric cars, and I’ll have to start from scratch.

Stefano

In conversation with Nicola Gerundino

I’ve done a lot in here, and I still do. I started out as the wing’s meal porter, then I took a digitalisation course, and I scanned Court of Assizes documents from the bunker courtroom between 2022 and 2024. I’ve been a volunteer at the wing library for nearly four years, and I also work as a scrivener, dealing with all sorts of important paperwork for prisoners: applications to the court, requests to the governor, and so on. I also have an active Article 21. There are three types: intramural, public land, and extramural. I have the third, which would let me leave prison for work. I’m just waiting for a job placement.

I’m glad I discovered work here in prison because I grew up in an environment where working wasn’t even part of the conversation. I’ve even figured out what I like doing: gardening. I enjoy being in contact with nature, and my goal once I’m out is to open a landscaping company. If you ask me to be a builder, I’ll tell you no! Being a carpenter won’t work either because I’m really allergic to dust. I don’t get on well with books for the same reason. Actually, I don’t get on with reading at all! I only like one type of book, and that’s books about black magic. Obviously, you can’t find those in prison, but I’ve got one very old one that someone brought in for me. There are three types of magic: white, red, and black. Lots of people say this stuff doesn’t exist, but I say it does. I don’t practise magic, though. I can read it, I can tell who’s got it on them, but I don’t use it because I’m not a bad person. I just like reading about it, understanding how it works, flicking through the pages. It’s a passion I got from my mother—she was Christian, very devout, but also very pragmatic. I’m Roma. I come from quite a particular people; plenty of us read palms, for example. But I’m the only one of my siblings—there are eighteen of us—who inherited it.

I believe in dreams too. Dreams tell you what might happen: every symbol has a meaning, and I’ve studied them all. Take the sea. If it’s black, it means tears of pain; if it’s clear or white, it means tears of joy. If you dream about blood or something red, that means you’ll get good news, something that’ll make you feel happy or emotional, like a baby being born. If you dream about a road or a path, it means that one day you’ll get where you want to go, even if you don’t in the dream. That one works the opposite to what people think. In prison, you dream, and you don’t dream. I’d rather not dream because I know dreams. I know they can be negative and they always tell the truth, so when I dream something I shouldn’t, it really affects my mood.

Many prisoners dream they never get out; others dream of their partner, which is not a good thing. In dreams, the male figure is positive; women represent a desire you can’t fulfil. Even dreaming about freedom is wrong because dreams work in reverse: the dream tells you you’re leaving, but it’s actually confirming you’re here and you’re not free. If you dream about freedom, sooner or later you’ll open your eyes and see the bars. And you need to be strong to handle that. That’s partly why I chose to be a scrivener and to become a peer supporter, to help other prisoners who aren’t as strong. I’ve been inside for ten years now; my skin’s a bit tougher. Some people tell me their dreams, but I don’t always say what they mean because, as I said, some meanings aren’t good. A dream is positive when it’s spontaneous, natural, and you’re calm on the inside.

There are a lot of spirits in prison, and they’re born from tragedies. I’m in a single cell, and sometimes I think about it at night.

Besides dreams, there are signs too. Your eye twitching is a warning—one eye tells you good things, the other tells you bad. I believe in déjà vu as well. I don’t believe in the afterlife, I’m an atheist, but I believe that at some point we reincarnate into something else. I also believe in spirits. As a kid I didn’t, but when I was 15, I met one in a park one summer evening. I was sitting on a bench with my girlfriend when a pinecone fell on my head, and she saw a person who immediately disappeared. A few days later, I realised it was a boy who’d died there, telling me to leave.

There are bad spirits, good spirits, and spirits that want you to stay away from their place. Good spirits are the ones who die old—people who lived their lives and died naturally, so they’re peaceful. They might warn you, they might even joke or touch you. When you find a bruise on your body and you’ve no idea where it came from, it’s because a spirit touched you. Those who die angry, for example, someone in their twenties who dies in an accident, become negative spirits. They inspire anxiety, fear, and all the other things they felt, especially when you’re on their territory. There are a lot of spirits in prison, and they’re born from tragedies. I’m in a single cell, and sometimes I think about it at night. Where I come from, they say that when spirits pass through they’re the cleanest beings in the world, so I turn my T-shirt inside out with the dirty side facing out, so the spirit won’t come close.

I’m not religious, I don’t keep saints, just a picture of my mother and her holy cards. We had a wonderful relationship, but I couldn’t say goodbye when she died a year ago; there were issues with the GFM request [permission for Serious Family Reasons, Ed.]. I was only able to go to the cemetery afterwards. I took her barley coffee, because that’s what she drank, and sweetener. I cleaned the grave and did a few other things. I got emotional, but we have different customs, we live these things differently. My wish is to have her moved, in about ten years, to where her mother is buried in Montenegro, because it’s right that they’re together. You never separate family—that way, no one ends up alone.

Ezio

In conversation with Giulio Pecci

It’s not prison that makes the inmates, it’s the inmates that make the prison. I’ve got a whole-life sentence. I’m in for good. Inside, I’ve been president of Legambiente, I worked as a sacristan for five years, I chaired the sports committee, and I spent 15 years in the workshop making nativity scenes.

I like helping people, giving a hand to people who are worse off than I am. I’ve realised it makes me feel better, but I do it quietly. I think it’s a way of trying to repair some of the damage I caused while still keeping my dignity. It means having respect for yourself, not betraying who you are. And for me, not apologising is part of that respect because it’d feel hypocritical.

I’m trying to rebuild a life in here. Even though the old one’s gone forever, I can only move forward. Sometimes I have to hit rock bottom, tear myself open inside, really sit with the pain. Only then can I get through it, and in those moments, I’m scared of the beast I’ve got in me. It’s like the prison is trying to drag it back out again, but I refuse to play along.

Rebibbia is a huge machine you can’t understand from the outside, all hidden dynamics and undercurrents. Everyone wears a mask in here, every day. But I made a promise to my daughters—I didn’t see either of them being born—and I’ve got to hold the line and keep myself straight.

I discovered writing on the inside. I can bang out ten or fifteen pages a night, and I put everything into it. I write in one go, mostly letters. Out there, everyone’s glued to their phones, which makes people feel close without ever letting you touch them. Writing a letter is more intimate; it creates a different kind of bond. Once I wrote a story about the coffee machine, about that smell that takes me straight back home, to my daughter. Edoardo Albinati even asked me to write a book, but I said no. I’ve found another kind of life in here, but the fear of normality still hangs over me.

Mohamed

In conversation with Giulio Pecci

I came to Italy from Tunisia, arriving in Lampedusa in 2011. From there, I went to Bologna, where I’d play football in the street with mates. For as long as I can remember, I’ve had a ball at my feet. One day, a guy clocked me, a carabinieri who coached football on the side. I didn’t speak Italian, so another Tunisian lad translated for me: “Listen, he said you play well, he wants to take you for a trial with Bologna FC.” He took me to his place and then to training. When they put me on the pitch and saw how I played, they immediately said, “You’re good, we’ll offer you a contract.” Then one day, a guy from my town slipped some hash into my pocket without me knowing. It fell out on the floor, right in front of everyone in the changing room, and I started arguing with the coach. From that moment, everything changed, and I found myself on my own.

That’s when I came to Rome. I played five-a-side with Francesco Totti—I got us to the final, I swear. Totti’s too good. He’d always give me fifty euros; he’d turn up with these wads of fifties. Then, in 2015, they stopped me while I was driving. I had documents, my licence, everything. There was a mate in the car with me, but I didn’t know he was being tailed because he had drugs on him. I couldn’t grass him up, so even though I had nothing to do with it, they gave us both two years.

When I got out in 2018, I moved to France because there was no work in Rome. I met a Romanian girl. She was a nun, but after meeting me, she converted to Islam to be with me. I had kids with her, even though I already had a partner and kids in Rome, also with a woman who was half Romanian. You know, Romanian women have a culture similar to Tunisian women; they respect their husbands, and I need a woman who respects me. When I came back here, I worked as a rider for Glovo. Then one night, a guy opened his car door in the street and got out. He wanted a fight. He was a carabinieri in plain clothes, with two women, and I think he was drunk or high. We ended up fighting, and he fell and hit his head. After two days in a coma, he died. In the moment, I panicked and ran, then I handed myself in. That was 2023, and now I’ve got five years left to serve.

Some people seem to actually like prison; they just go in and out.

It was hard at the beginning. When you’ve got kids, you know… I take responsibility seriously, the way my father taught me: your wife and children stay with you till the end. That’s what hurt the most—leaving them when they were small. It was hard dealing with certain characters in here too. I had so much anger at first, but I had to be careful not to fuck up again. Some people seem to actually like prison; they just go in and out. I always tell them: I’m not a jailbird, I’m here with you, but I don’t want trouble. That’s why the friends I’ve got in here are all students and athletes, never the fuck-ups. Those people latch onto you like a virus, and if you don’t keep your distance, you go down with them. I’m already in here because of one punch. Imagine if I make another mistake. Besides, my wing G9 is the best in Rebibbia. It’s the calmest, the one where we stick together and there’s no fighting, no bullying, no disrespect.

The other day, I said exactly that to a priest, and he liked my mindset. I’m Muslim, and I don’t really need priests because I’m in direct contact with God. I pray five times a day. But talking about religion matters. Think about it: we’re suffering in this life—look at me, I ended up in prison—but in the next one? Are we supposed to waste that one too? I’d be an idiot to do that. No, I try to live well here and now, so I don’t lose it because as soon as you die you go to paradise.

All I hope is to get out soon because I don’t have any plans in here. I just want to play sport. I’m crazy about football. Why should I be angry or cry or play the victim? I wouldn’t be a man. I’ve ended up in here, and I’ve got to learn from my mistake and, once I’m out, never do it again. Like being at school.

Riccardo

In conversation with Federica Delogu

I was born in Genzano di Roma and grew up in Ciampino. I’ve been inside Rebibbia since May 2024. I’d already been in once before, for nine months in 2020, at Regina Coeli, with my brothers Simone and Davide. I was acquitted and they were convicted, four years each. But just as I was putting my personal and professional life back together, the final ruling came through: prison. I went back in on 28 May 2024, and that same day my brother Davide, who was locked up in Velletri, had a respiratory crisis in his cell. It was night, the cell was locked, and he died of an asthma attack on his birthday, the very day I went into that prison, the one I’d chosen to go to. I’ve carried this pain ever since. He’s always on my mind. I dream about him every night. Every time I hear a bang, every time someone feels ill, my anxiety shoots through the roof. I try not to think about it, try to fill my days as much as I can, but it’s hard.

After five months in Velletri, I was moved here. I run for 45 minutes every morning, work out in the little room doing bodyweight exercises because my wing doesn’t have a proper gym, and I listen to music. Sport helps me work through the thoughts and the stress. Without it you risk turning into a vegetable. Last year I went to school and signed up for the theatre course, but I had to quit because I couldn’t act. The trauma kept coming back up.

Just as they brought me here, my twin, Simone, opened a bar in Torvaianica. That was our dream for the three of us. Simone’s a pastry chef, Davide was a barman, and I’ve always worked in hospitality as a pizza maker, commis chef, then chef. Mum’s an accountant. To open the business, we had to sell the flat we had, but we bought two identical, mirror-image ones by the sea, so when I’m out we can live close. I started working early, at 16, with exactly that goal: to pool our strengths and run a business. That was our dream, and we made it happen, in honour of our brother too. That’s why we named the bar after him. I haven’t seen it yet. They sent photos by email, but because everything has to be scanned, I’ve only seen them in black and white. It looks nice though. Small, with a little square and tables outside. Same with the flat; I’ve only seen it like that.

In the meantime, I’d like to be hired in here because time flies in the kitchen. It’s a way to detach from this reality and learn something useful

Meanwhile, Simone had a baby girl. She was born while I was inside. She’ll be one soon. They bring her to visits a lot. I saw her as a newborn, and bit by bit she’s getting bigger, saying her first words. She’s beautiful. I can’t wait to spend all my time with her. My mum and my sister, from my mum’s second marriage, come often too, and my dad with his wife and their son, my other brother. At visits we eat together. I bring sweets or fried things we make inside. Usually we eat cornetti because they come in the morning. Pistachio for my mum, custard for my dad. If the visit’s later, I bring courgette flowers and supplì, and for special occasions I get pizzas from G8. We get six visits a month and four calls, plus emails. A few friends write to me—two of Davide’s friends, his ex, and one of mine.

I’m really grateful they’re still here for me, that they care how I’m doing. I pushed a lot of people away after what happened. It shattered my life. Davide was the backbone of our family. Two years older, same friends, same crowd. But it taught me something: the importance of life, the value of not wasting it. I don’t ever want to set foot in a place like this again, and this is the last stretch I have to serve. Now I want to change my life, start a family of my own. I hope they let me go to our bar on day release. I’ve learned how to make gelato, semifreddo, and granita in here, and I’ve just got certificates in ice-cream making, HACCP, and workplace safety. The plan is to open a lab next to the bar so we can make our own gelato.

In the meantime, I’d like to be hired in here because time flies in the kitchen. It’s a way to detach from this reality and learn something useful because I’m not the one who cooks in our cell—it’s the guy I share it with. We met in here, but he’s become a proper friend. Now we’re like brothers. He’s been cooking for years, and he’s good. For dinner, we usually have meat with salad, or piadine. We eat at half seven, then we take turns in the shower, and at eight they do the meds round. I don’t take anything, just ask for a tranquilliser now and then if I need it. After that we watch a film, and I always hope there’s a good one on, because at least you fall asleep easier. We talk about everything, confide in each other, tell each other how things are outside. I’ll always be grateful to him for helping me through this part of my life. When this is over, everything will be new. I hope for the best, so I can finally put down this pain that’s so heavy and so hard to face.

Emiliano

In conversation with Federica Delogu

I’m Emiliano, I’m 51, and I’ve been in here for about a year. I’m from this neighbourhood, Rebibbia, my house is literally around the corner. I could see the windows of my kids’ bedrooms from my first cell. I had to ask to move because I was spending all day leaning out of the window looking at them. I’ve got three kids: one’s 23, one’s 18, and the little one’s 7. The oldest has just made me a grandad, nearly two months ago, but I haven’t seen my granddaughter yet, only photos. I don’t want a newborn breathing the air in here. My family walks over to visit every week. I can’t wait for them to come, and when they leave, I feel awful for the rest of the day. Now the holidays are over, the boys are back at work, and the little one’s back at school, so I’ve got to get used to seeing them less.

I’ve had a pretty rough life, but it never made me bitter. I was born in Torpignattara and lived there as a kid in a shanty area until 1983, when my parents squatted the council flats here. So I feel like I’m half Torpignattara, half Rebibbia. Both neighbourhoods are home. But Rebibbia is a special place, halfway between San Basilio, which is right on the edge of the city, and the centre of Rome. It’s beautiful, full of greenery, full of good people, it even has the metro, and it’s multicultural. It was completely different when we got here: just fields and sheep, and they were putting up the big council blocks. Compared to Torpignattara, it felt like the countryside; it didn’t even feel like Rome. Forty years have gone by since then, and, like all of Rome, it’s grown massively.

I’ve really lived this neighbourhood, and I still do. I’m one of the founders of the local committee, Mammut. Now that I’m inside, they’re always writing to me, sending photos from the neighbourhood festival we usually organise together. We fill a whole park with people, with bouncy castles for the kids, all done off our own backs, and I usually take care of the fireworks. With the committee, at Christmas and New Year, we come here outside the prison with a marching band and play for the inmates. Last year I was outside with the band, this year I’ll be listening from inside. I’ve always done my bit for the neighbourhood: during the pandemic, we delivered food parcels to families, and even now, if someone needs help, we find a way. We run an after-school programme with fifty kids, we clean the green spaces, and we even built a football pitch. And because I’m a decorator, I’ve helped all the street artists who’ve painted murals around here: bringing paint and materials, eating together. Normally, I draw too, but not at this point in my life. Drawing is something you do when you’re well, or at least that’s how it is for me. I draw when I’m calm, with a clear head.

When you do something good for your neighbourhood, someone always remembers, and they know you’re a good person, even if you’re in here, and that really warms your heart.

That’s why a lot of people know me here, and why I’m well-liked. When you do something good for your neighbourhood, someone always remembers, and they know you’re a good person, even if you’re in here, and that really warms your heart. People in Rebibbia don’t think much about the fact that there’s a prison here. It becomes normal, just like it’s normal that the neighbourhood is named after the prison. Everyone walks past it because it’s a shortcut between two parts of the area. The prison is part of the neighbourhood, but as long as you’re only walking by, it’s just a building. The neighbourhood knows it’s here, but it doesn’t understand it. It doesn’t know the world inside. I first came in 15 years ago for four months, and now I’m back.

You need patience here, loads of it, and you hope time goes quickly, even though the days drag on forever. I try to keep myself really busy: I work, I’m the wing painter, and sometimes they call me for outside jobs too. I do the shopping for my cellmates—there are six of us—and I keep everyone’s accounts, I help in the kitchen, I basically do all the housework.

What’s it like having six in one cell? I don’t know how to explain it because there isn’t a word for what it does to you, and I hope you never have to understand it. Just think: if two people can clash at home, imagine six of you in a tiny room with one bathroom, and the kitchen is inside the bathroom. You’re always on the edge of an argument. One morning, you wake up in a bad mood, the next morning it’s me. It takes the tiniest thing to kick off a row. And we’re actually pretty good at avoiding them, every day, every minute.

You know when you say, “I just want a moment to myself, just ten minutes”? That moment doesn’t exist in here. Maybe at night, but only lying on your back staring at the ceiling, not talking, not making a sound, even though there’s always noise. Never a moment of proper peace. If we’re quiet, the cell next door is kicking off till late. Then, after midnight, someone shouts, and everyone calms down. But absolute silence? That doesn’t exist.

Simone

In conversation with Isabella De Silvestro

I’m twenty-three—one of the youngest in here—but I learned straight away that if you respect people, they respect you back. Before coming to Rebibbia, I did two years of house arrest. I was lucky enough to be allowed out for work because I had a full-time contract in removals and transport: packing, loading, unloading. I thought that stability would help me get probation; I even asked if I could volunteer with the Civil Protection. I really thought that would keep me out, and instead they sent me here. Maybe it’s fair, maybe it’s not; that’s not for me to say. I just try to let time pass and think about the day I get out. It’s not far off now, so I’m hanging in there.

My first experience with prison was at Regina Coeli, where I spent three days waiting for my confirmation hearing. Heavy stuff. Everything there is tougher: the old, crumbling building, the atmosphere. Rebibbia is different, it’s a bit more liveable, but it’s still prison. You miss freedom, obviously, so you try to find ways to make the days mean something. And trust me, if you keep yourself busy not only do the days fly by, but at night, when you go to bed, you’re properly knackered. My days start early: in the morning I volunteer delivering groceries to the cells. It’s not a real job, but it keeps me busy, and for someone who’s always worked, that matters. In the afternoon I play cards or ping-pong, or I go down to the yard for a walk or a game of football. Soon I’ll be starting school too—I’ve enrolled, just waiting for lessons to begin. I wonder what going back to school will be like… it’s been eight years since I last set foot in one. Outside, I finished middle school and enrolled in hospitality school, but after failing my classes I dropped out. I did have a passion though: football. I even played a few matches in Eccellenza [Italian semi-pro league, Ed.] when I was sixteen, seventeen. I could’ve carried on, but I started working eight-hour shifts and couldn’t keep up with training anymore. It stopped being fun, so I quit.

What I know is that it’s been three years since I last saw the sea.

I grew up in Primavalle. Do I like it? Do I not like it? I don’t know—I’ve lived there my whole life, it’s home. Everything is there: my family, my friends, my girlfriend. We’ve been together almost six years. We lived together in my grandma’s house, and when she passed away it was just the two of us. I owe her a lot. She comes to see me every week, she’s never left me on my own. My friends write to me too; they send me packages, clothes, whatever I need. They make me feel like I haven’t forgotten anyone and no one’s forgotten me.

I’ve got good relationships in here too. The cell is small, sure, but we’ve found a kind of harmony. There are four of us and we all get along. Yeah, we squabble sometimes, but nothing serious. I cook for everyone three or four nights a week; I taught myself on the outside. Thinking back to the early days, I remember it being tough, especially mentally. I didn’t know how many years I’d get or how things would turn out. It hits you hard, it forces you to rethink everything. But if there’s one thing I’ve learned in these years, it’s that when they take everything away from you, the one thing you’ve still got is your smile: that stays, it’s yours, you can protect it. To keep myself going, I think about the day I’ll be able to get back to work and rebuild a normal life. I miss so many things: the sea, dinner out, going on a trip with my girlfriend. Are they trivial things? Maybe, maybe not. What I know is that it’s been three years since I last saw the sea.

Giovanni

In conversation with Giulio Pecci

I got into IT in Sicily when I was ten, with my first-ever computer: a Commodore 64. Then I went to university in Brussels and did a master’s and a post-grad specialisation in computer science. Before I started working, I did my military service. It was compulsory back then. They sent me to Iraq during the Gulf War, and I worked in the command centre wearing a radar vest. I got my pilot’s licence too, which I really enjoy. And honestly, flying a plane is easier than driving a car: when you’re up there, you just have to anticipate what might happen, which is the easiest thing in the world.

I only joined the military for the money; there was no talk of peace or any of that. Just money. I also worked with Microsoft; we developed modules for one of their biggest projects, the Genome DNA-mapping project.

That’s what I do: I’m a computer engineer. And I can tell you for sure that what matters most today isn’t the tech you “see”, but cybersecurity. In the relationship between computer and human, it’s never the computer that fucks up: the weak link is always the human being, stupid by nature. You’re born a fool, you die an idiot. The human factor is 90% of all problems. There’s something I always say, it was even the title of my thesis: “a switched-off computer is a safe computer.” When I was at uni in Brussels, I actually found a security flaw in some IT systems while working with IBM on credit card and transaction systems. That’s when I created the algorithm that got me into trouble. Basically, I shifted some money into foreign accounts… and so, eighteen years later, here I am. I’ve been in Rebibbia since 8 March 2025, and I’m already sick of it. I try to take each day as it comes, find ways to pass the time. I even learned how to play cards: scopone scientifico, scala quaranta, that kind of stuff. Things I never had time for on the outside.

Intelligence isn’t looked on kindly in prison—if you stand out from the average, you’re a problem. From that point of view, prison is anything but rehabilitative. As for living together in here, there’s a great Sicilian saying, one of the best: “mangia e futtitinni” or “eat and don’t give a fuck”. Meaning basically: everyone’s screwed and smiling. It’s like the jungle in here: you either give orders or you take them, and it’s up to you whether people accept or reject you. But you can also have relationships with serious people and having someone you get along with and can share things with is fundamental. Prison definitely makes you see life differently. Before I got arrested, I thought everyone inside was scum.

I consider myself a normal person who made a mistake—a mistake that involved moving small amounts of money between accounts. And that’s why I’m remorseful: I should’ve moved way more! [He laughs, Ed.]. But seriously, how the hell are you supposed to “rehabilitate” at 55? They’re gonna teach me what, exactly? And my crime was eighteen years ago… I’m already a different person.

The two things I miss in here are pussy and my company.

I’m trying to figure out how to get an alternative sentence so I can get out as soon as possible and get back to work: I’ve got my company, and there’s no way to do IT in here. I basically have to rely on the Holy Spirit, if he even exists.

I run the company through my lawyers, but it’s tough because I’m used to handling everything myself. I always say I trust two people: one is me, and the other one isn’t you. And I’ve got another saying: “There are three ways to do things: the right way, the wrong way, or the Giovanni Sallemi way.”

Right now, I have no idea how things are going at the company. We don’t have computers or internet in here, no way to communicate, so I always hear everything late, like four days after they happen. If it all goes to shit, I’ve got money and I’ll just fuck it all off. I’m 55, I’m hardly a newbie: I’ll have my fun, whatever I did before as a married man, I’ll do now as a single one. I’ve been married, been divorced… My problem is sometimes I don’t think with the head up here, but with the other one. The two things I miss in here are pussy and my company.

I don’t have a family as such, but I do have a daughter who’s about to turn eighteen. She lives in Budapest. She’s brilliant, but right now I can’t speak to her because things are tense with her mum. I’ve never actually spoken to her. I don’t even do phone calls, I don’t talk to anyone. Still, I’m trying to get in touch with her to explain everything. I hope I can meet her and her mum so we can talk, because what matters is having a real conversation.

You know how in Sicily the bar is basically the internet, right? In here, your wing is the internet. Everything is everyone’s business. If I want to know what you ate, what you shat… anything! It’s hard to get your bearings in here; it’s an emptiness in plain sight. Everyone does whatever they want, but what matters is knowing who you’re talking to, who you’re dealing with, even though you have to deal with everyone in the end, just like in real life.

And that brings us back to what I said before: everyone’s screwed and smiling. That’s the key. It’s just a more sophisticated version of putting on a brave face.

Giuseppe

In conversation with Isabella De Silvestro

My name’s Giuseppe, and my hands have always been my greatest strength. I’ve been a barber my whole life, ever since I was a kid. I’ve got tattoos on my arm of my grandfather’s face so I don’t forget him, and of the tools of the trade—scissors, razor, brush—plus the year I started, 1989. “Barber life”: that’s me. When my mum used to take me to the local barber, I’d sit there staring, completely hooked. One day, he said, “When school’s out, come work here with me.” And that was it. I had a passion for it, almost like I was born with it. When I was little, I’d cut my sister’s dolls’ hair, and I’d shave balloons with my dad’s brush and foam. If the balloon burst, it meant I still wasn’t good enough to shave a man without nicking him.

I never finished secondary school; I stopped after middle school. I was already working. My mum said that I needed to keep busy while she was at work, not hang around the streets. So I’d spend hours cutting hair. I did eight years as an apprentice, earning 15,000 lira a week. Bit by bit, I opened my own shops. I ended up with three, each one better than the last. I grafted hard, twelve-hour days, and with the money I built a life for myself: a house by the sea, a family. But then things got complicated. I struggled with addiction. Ups and downs, rehab, long stretches clean, then relapses. My dad went through the same before me. He did seven rehab programmes. He eventually got clean, but he left everything behind: his wife, his kids, his home. When I was young, I had to figure things out on my own, act a bit like a dad and a bit like a husband. By 18, I was already bringing money home.

If someone can pay, it’s usually with a pack of cigarettes. If they can’t, I still cut their hair.

Then my grandfather died, the only person I really found comfort in, and that’s when I lost my head. He was like a father to me. Proper Neapolitan, eleven kids, but he always came to see us—my mum was his favourite. He’d spend whole summers at ours, three or four months at a time. As a kid, I followed him everywhere. He treated me like a son. When he died, my whole world collapsed. I didn’t have anything to anchor me anymore. That’s when everything went downhill. I didn’t want to work, didn’t want to go out, didn’t even want to wash. My mates would drag me out of bed and shove me under the shower to snap me out of it. It wasn’t an easy time, but I pulled through. Thinking of my kids gives me the strength to keep going. I’ve got three. The oldest works at the airport in the mornings and cuts hair in the afternoons. He keeps the shops going, looks after the clients, stays well clear of drugs, and he can’t even stand the smell of wine. The other two are still little. They come to see me in the green area, which is a bit less grim than the visit room because you can play and forget, just for a moment, that you’re in prison.

My days in here start at seven. I get up, have breakfast, clean the cell. Then I go down to the yard, where the gym is too: a football pitch, a few weights, enough to kill some time. In the afternoon, some people read, some play cards, some sleep. I can’t really read: I’m dyslexic and dysgraphic. I only found out recently, when I realised my youngest two have the same thing. I only learn if I see or hear something. Reading doesn’t stick. I get mixed up with letters, double consonants, commas. But it’s fine. Everyone’s got their thing. So in the afternoons I do a few haircuts for the lads, especially if someone’s got a visit the next day. My tools are basic: a battery clipper and a spray bottle I made out of an old perfume bottle. No scissors because only the official wing barbers are allowed those.

If someone can pay, it’s usually with a pack of cigarettes. If they can’t, I still cut their hair. The good thing about my trade is that it’ll always be needed. My old boss used to say, “For you to starve, people would have to be born without heads. Even in a war you’ll get by: you barter with the greengrocer, the butcher… You don’t need money.”

He was right.

Mauro

In conversation with Isabella De Silvestro

My name’s Mauro, and I’ve been in Rebibbia since 6 April 2023. But it’s not my first time: my first stretch was from 2001 to 2011. Ten full years. First Frosinone, then Rieti, then here. When I came back, it felt like a different place. Twenty years ago, there was respect and manners. Today it’s different: six people crammed into a cell with one bathroom, and you’re cooking in there too. You’ve got to make do, as always. “These days you’ve got to look inside yourself and see what path you’re on. But every road leads you back to the same one, and the last stop is death. So…” I wrote that in my diary, where I note down everything. I don’t skip a single day, not even by accident. So if someone asks what I was doing on, say, 18 May 2024, I can tell them, down to the tiniest detail. I had a coffee in that lad’s cell, I sent a letter to Sandra, I lent two reds to the gypsy. What are reds? Marlboros. Currency. A box of hair dye—I always want jet-black hair—costs me a pouch of tobacco. Applying the dye? A pack of cigarettes. That’s how it works in here. If someone’s skint, they help out with small errands, and you pay them back with cigarettes or food you’ve bought from the canteen. It’s a whole survival economy of its own. And if you’re going to spend years here, you need to find a way to build yourself some kind of normality.

Cooking, for example, is a way to feel a bit at home, and I’m good in the kitchen. Before ending up here, I had restaurants, and I haven’t lost my touch: trippa alla romana, pasta and beans with sausage… even my Chinese cellmate rates it. We get on. Truth is, I get on with everyone, even the screws, who all know me by now. When I walked back into Rebibbia at the start of this second sentence, loads of them remembered me: “Back again, Cerci?” I’m a cheerful sort, I don’t let things get on top of me, and I keep myself busy. I write to my wife, Sandra, and to Andreotti too every now and then. Not the real one. Andreotti is my son, or rather my partner’s son, who’s become mine as well. I call him that because he’s a sly one. As a kid, he’d go into the corner shop for a sandwich and come out with two full bags, seeing as I was paying. We write to each other; we see each other in the green area during visits. For his eighteenth birthday, I wrote him a letter and had it read out loud in front of all his mates at the party. It was my way of being there from afar, to toast with him. I’ve printed several copies, which I keep in the folder I’ve made for him, for Andreotti: photos, letters, applications for permission to see him at visits or call him. But before Sandra and Andreotti, I had other lives—and one lifetime wouldn’t be enough to tell them all.

I grew up fast. I left school in my second year of middle school—I got my diploma in here. At 14, I ran away from home; at 17, I was already a father and living with my girlfriend’s family. One day, and this is going back years, I walked into a bar. A woman came up to me and asked, “Ever thought of being an actor?” I laughed. “You can make good money,” she said. But it was another line of acting… porn. I gave it a go, and for a while it worked, until my brother-in-law, a night guard, found out. One night, he turned on the TV and there I was, in full action. When I got home, my things had been chucked down the stairs. End of that story.

What are reds? Marlboros. Currency.

Then came the restaurants, money, parties, women. And trouble too. Right up to my arrest in 2001. They took me straight to Frosinone, which was a dump. But I made myself well-liked, and they transferred me to Rieti. A small prison, forty or fifty inmates, almost bearable. That’s where I started working in the kitchen. One day in the yard, I had an epileptic seizure. They flew me out by helicopter; I ended up in a coma for a week. When I woke up, I didn’t know where I was. I tore everything off, the tubes, the catheter, with machines beeping and people dying around me. I lost it and just started shouting, “Get me out, get me out!” They wanted to send me to a forensic psychiatric hospital, basically a nut house, but luckily, I calmed down, and they took me back to prison. When I got back to Rieti, the governor called me into his office and, in a fatherly tone, said: “Mauro, your final sentence has arrived, it’s eighteen years. I’m really sorry.” My world just fell in. But he added, “You can’t stay here. I’m sending you to Rebibbia, to G8.” G8 was the so-called “good” wing, they used to say inmates would’ve paid to get in. More activities, more freedom, if you can call it that.

When I got there, I met a guy from my town. I told him I couldn’t handle it, that eighteen years felt endless. He said, “Come with me, let’s take a walk.” He took me down the corridor, where the release dates were written up outside every cell. “Read ‘em,” he said. “2052, 2060, 2047, 2062.” Then: “Release date: never.” He looked at me and laughed: “You get it, Mauro? You can’t go round saying you’ve got eighteen years—they’ll batter you. You’re basically a free man!”

From that day on, I stopped despairing. Eighteen years, in the end, wasn’t forever. You need patience and a bit of humour. Today, even if prison is what it is, I’m still myself. Lively, a bit vain, always on the move. I barter, I cook, I laugh, I act, I write, I tell stories, I listen to music. I like neomelodici, Pooh, and lately even Achille Lauro. Every now and then, I scribble down a lyric to send to Sandra. I even made a film that won awards, L’ora d’amore. To survive this place, you’ve got to keep your spirits up. Everything else—even time—passes in the end.

Gabriele

In conversation with Giulio Pecci

The first time I ever experienced tenderness, it scared the hell out of me. My first girlfriend would hug me and give me little kisses, and I didn’t know what the fuck that feeling was—I’d practically shove her off. There’d never been any tenderness in my family. My dad’s Calabrian, my mum’s Filipino, and we lived in Tivoli, where I also went to art school, even though I was born on Tiber Island. I left home early, at 15, after my brother had an accident. We were messing about with some petrol, and he caught fire by mistake. He survived, but with severe burns over half his body. From then, my family basically fell apart, my mum got depressed, and I copped the blame. But I was just a kid.

I moved in with my girlfriend and started looking out for myself early. Not long after, I had a crash on my scooter that nearly killed me. I smashed into a pole and my mates thought I was dead, but I came out of it with 150 stitches across my pelvis and months where I couldn’t work. Back then, I was helping out a lot at a swimming pool, and the owner really liked me. He’d had a rough life himself—he was missing an arm and was paralysed—and he stuck by me after the accident. He was also the first person to show me how tattooing works, how to put together a homemade machine. From that moment I started working. I’d nick sewing needles from my mum, ink from school, and I’d tattoo people. That’s how I saved enough to buy a proper kit and pay for tattoo school in Furio Camillo, where I graduated top of the class. I love realistic tattooing, especially Chicano style. I couldn’t get my head around how people could draw so beautifully and precisely on paper, let alone on skin—it fascinated me.

The first time I ever experienced tenderness, it scared the hell out of me.

I committed my first offences very young, simply because I didn’t have any money, and my parents never gave me any. I first went to prison at 17, after a fight over a debt. I’d reached my limit. That changed everything. I ended up in hospital, completely smashed up: legs, arms, head. When I got home, they came for me and forced me into a brutal forced psychiatric hold for forty days. I lost it in there, mainly because of the meds. My memories from then all scrambled—of plexiglass windows, of being tied to a bed... I remember once I gave a bit of weed I’d smuggled in to another lad just for a bit of company. But he freaked out and a massive fight kicked off; we trashed the place. They found me asleep in the garden. And to think that before the forced hold and the psychiatric unit, I’d never touched anything harder than a joint with mates or my girlfriend. I only started the synthetic stuff afterwards.

I moved around a lot—different places, units, prisons, probation. I ended up back in Rebibbia because during a probation period, I rode past a shop on my scooter that looked empty. I don’t know what came over me: I passed it a couple of times, then went in to rob it. While I was doing it, I got stabbed twice, and that’s how I ended up back here.

And the mad thing is, I had money. I was working well, had loads of loyal clients who asked for me by name. I even managed to build a house from scratch in Guidonia. I drew up the plans myself, with help from an architect. I even laid the drive myself. If I’d finished it before coming back in, I would’ve rented it out and had a steady income. Despite everything, I got a lot done off my own back.

Massimiliano

In conversation with Giulio Pecci

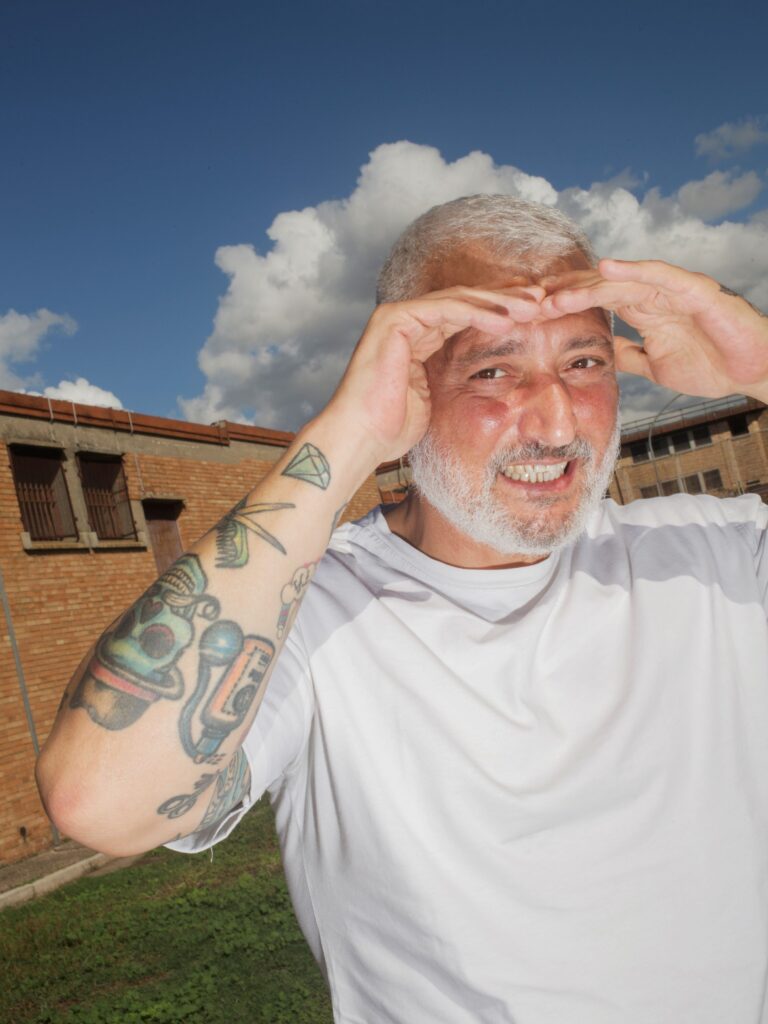

I’m Slavic, Roma, and Muslim. Born in Rome in ’96. I lived in Laurentino 38 for years, then moved to Sardinia after my parents split up. But Rome is Rome. It’s my city. I grew up selling at vintage markets—Porta Portese, Uscita 24, Togliatti—all of them really, because meanwhile I was also doing removals and clearing out basements. The strangest thing I ever sold was this really old camera, like a Polaroid. It reminded me of my mum, who used one like that when she was young, so when my daughter was born, I bought an analogue one for her, the kind that runs on batteries. Like giving her the same memory.

I’ve been in here eight months for something that happened in 2020. And I can tell you now, time stops in here. It’s like it’s always Sunday. The more you keep busy, the more you fill your head, and the more you forget you’re inside. But the second you stop, your mind goes straight to your family. That’s when everything freezes, when you realise the value of the small things. My partner calling me to go get ice cream with the kids, taking them to school, just being there in the moment… You think about all that, and you think about how you should’ve done it more often.

They’re what keep me going, but it’s been eight months since I’ve seen my kids. I can’t always get them in because they’re foreigners like me. Even though they were born here, they still don’t have Italian ID cards. I’m trying to sort it with my lawyer and an educator, but there’s always some issue. You wait months for answers, then the magistrate might block the whole process over the smallest bullshit—and it depends on what kind of person that magistrate is. You wait for the visit, you’re anxious because you don’t know how it’ll go. You’ve only got an hour, so you can’t say everything you want to say. You’re happy, but always against the clock. One of my cellmates hasn’t seen anyone for over five months. When he knows it’s visiting day, he gets depressed, obviously. We try to keep him up, distract him, joke around. Some people go years without seeing their family because of documents or distance. I write now and then to my partner and to my dad, who’s inside too, in Sardinia. We write from one prison to another, which is kind of funny, but we tell each other the usual father-and-son stuff: keep your head up, behave, don’t fight.

“There are beautiful things you forget straight away, and beautiful things you never forget, not even after death.”

In here, being comfortable in your cell is the most important thing, and I’ve ended up with lads I mostly knew from outside. There are six of us. I wake up at five, make myself a coffee, have a chat, read the paper, which is our only window onto the outside. They open up at half eight, and I head to the gym. For lunch, we make sandwiches, and we sort dinner straight after because that’s the main meal. I’m the cook. I make food for everyone else first, then myself. We even did Ramadan together. During that time, the prison changes because the rhythm changes. Meals come after sunset and before dawn, and on the last day, an imam comes in to lead the prayer. I’ve been Muslim for ten years. It was my choice. My mum’s Christian, my dad’s Muslim, and they let me decide for myself.

The tattoos you see are for different reasons. One’s for my daughter. One I got randomly from someone I met at a market. Then there’s this quote from an old black-and-white film: “There are beautiful things you forget straight away, and beautiful things you never forget, not even after death.” Another one is for my partner, the only person who gives me strength in here. It’s not easy for her either. If we suffer in here, they suffer out there. It’s hard, but I’ve realised that if you can’t get through things, you can’t say you’ve lived.

In here, I’ve had to learn how to manage anger. When I’m in that mood, I shut down completely, keep everything in. I never know how I’ll react. Even during visits, sometimes my partner is crying, and I just sit there, silent, looking at her. Not a single tear. But holding it all in does me no good. A while back, I got really sick: in three months, I lost 30 kilos, then got an infection and lost another 15. The doctors told me, “You’re keeping everything bottled up, you’re abusing meds and painkillers,” especially because I’ve got other health issues too. And in the eight months I’ve been in, I’ve only seen the psychologist three times because there are just too many inmates. I’ve only got one hope: that one day they’ll come and say, “Massimiliano, you’re free.” Then I’ll laugh a bit, pack my things, walk out, and never come back again.

Gennaro

In conversation with Giulio Pecci

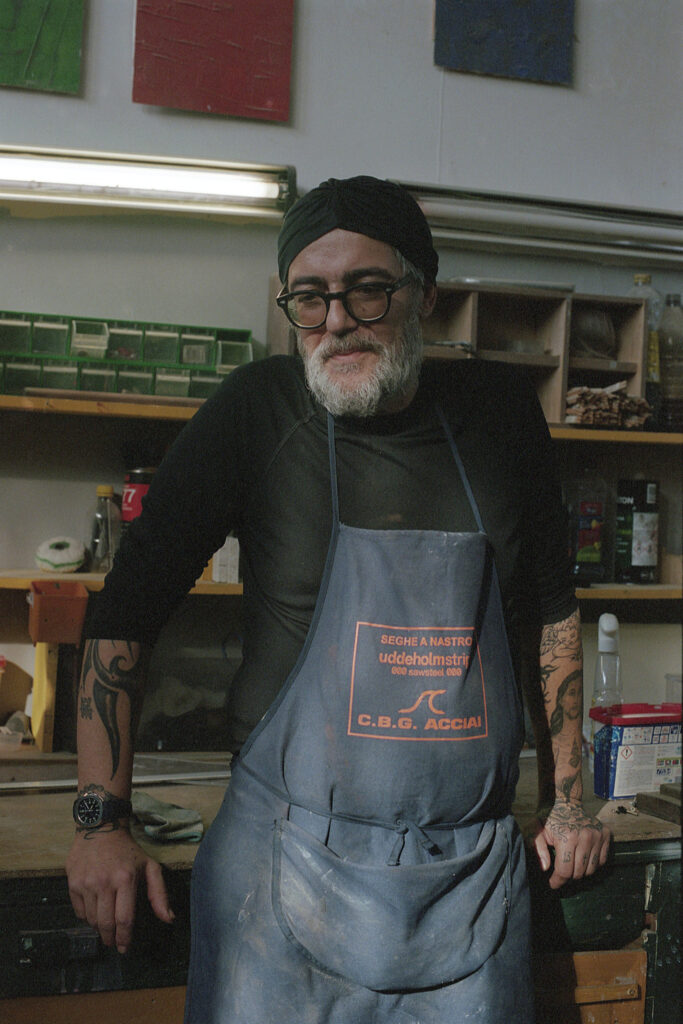

I went into prison in 2003. I got out for ten months in 2008, then I got arrested again, and I haven’t been out since. From Arezzo to San Gimignano, from Marassi to Verona, then Ancona, Pavia, and so on until Rebibbia. I’m 57 years old, born in 1969. I’ve lived outside a bit but, really, I grew up in prison. In these 22 years, I’ve lost half my family: my son, my father, and two sisters. I’ll tell you the truth: after I lost my son, prison stopped hurting. The death of a child takes everything away from you, it’s a weight you carry for life. You can’t get rid of the pain—that would be like getting rid of your child. You just have to live with it. From that day I’ve tried to get better for him. I started seeing prison as a punishment, and I prayed to God asking him why him and not me. I threw myself into work, but I know that if I hadn’t had my other daughter, I’d have gone under completely. She’s the reason I got myself transferred to Rebibbia in 2015. It’s awful to say, but at the beginning, my mind kept going rope or pain, rope or pain. If it hadn’t been for Maria… I also did some work with a psychologist and a psychiatrist because the cocaine abuse on the outside, together with everything I’d lost, gave me panic attacks. What woodwork means to me is committing to something positive. It’s a place for people who want to express themselves. We opened it a while ago. I don’t “work” here; this is like a hobby room for me.

I’m at the end of my sentence now, and I can tell you Rebibbia is one of the best prisons in Italy, and I’ve been in a lot. After Poggioreale and Secondigliano, this feels like Gardaland. It’s a huge prison that lets you do loads of things: school, theatre, the coffee-roasting workshop where I worked for eight years, and the woodshop I helped start with others. Since I build nativity scenes, the senior officer at the time assigned me a few lads so I could teach them how to make that kind of thing. My grandfather was from Naples, Piazza Carlo III, and he had a nativity workshop in San Gregorio Armeno. Every wing here makes its own nativity scene, then a panel of judges comes in and hands out prizes on Twelfth Night, so that’s what I’m focusing on now. But I don’t work in the woodshop—it’s a hobby. A place for expression, something that demands commitment to something positive.

You can’t get rid of the pain—that would be like getting rid of your child. You just have to live with it.

They finally authorised me to take a miniature project out: a wooden house with a garden, lifelike down to the last detail. I’ve been working on it for four years, and my brother’s coming to pick it up and take it to Naples. Then the plan is to open a small shop here in Rome where I’ll build nativity scenes and little wooden pieces, since I’ve only got two years left before I’m out.

In the meantime, I’ve met two Popes. They even sent me to Pope Francis’s funeral. For the Jubilee, I built a miniature Holy Door out of wood taken from migrant boats, and they gave it to him as a gift. It’s a small door that opens, and behind it there’s a world with the sea, a light, and a desk with a Bible on it. When you open it, that’s what you see—all hand-carved. Salvini came here too, spent some time talking, and asked me to make a big nativity scene for what I think is their main headquarters. But commissions like that rarely happen, and often they don’t even let you do them. That’s the problem with this project: if you don’t make it pay, the lads understandably go and work somewhere else. If you don’t sell, you can’t even buy cigarettes, and if you’ve got no money in here, you’re “scamazzato”—fucked.

Prison helps you if you want it to, but you’ve got to want it. Even in the rough ones. Speaking from experience, you can do well anywhere. It’s like when drug addicts truly decide to stop, they just stop. If you don’t change inside, nothing helps. Something has to click. The death of my son was that click for me—I saw things in a different light. Now I’m on licence, I could get out under Article 21, but I don’t even want to. I prefer to finish these last two years and keep helping a few lads. Sometimes I make pieces for other prisoners, for their kids or grandkids—Pikachu, Spider-Man, cartoon figures, all in wood. I make benches, bookshelves, all sorts of things, but what I love is making nativity scenes. And not for faith, especially after my son died. I just like making them, full stop.

If I need to pray, I pray alone in my cell. If there’s someone up there listening, fine, but I’m not into confessing to a priest anymore. I mean—you confess, and then they lock up a priest in here for raping a girl, so who the hell am I confessing my sins to? It makes you wonder. So you stay in your cell, you pray, and you confess to yourself. In here you stop trusting authority figures because you see them getting banged up like everybody else. You come across anyone and everyone inside—like now Alemanno’s inside. Since he’s been here, I’ve seen more politicians in five months than in my whole twenty years in prison. La Russa, Salvini, all the big shots. And you ask yourself: why are they coming? Did it really take Alemanno for them to shine a light on the fact that there’s six of us in a cell cooking where we shit?

Stefano

In conversation with Federica Delogu

I’m a cook before anything else. I do it on the outside, where I make food for dozens of people at a time, and now I’ve become one in here too, although in here I’m cooking for six—meaning the lads in my cell, me included—and our “kitchen” is a little gas stove in the bathroom.

You can cook all sorts in prison. You can even build an oven out of aluminium trays folded into a pyramid, so it works like a hood that traps the heat. You’ve got to be inventive because there’s loads of things you’re not allowed to use. For example, knives are banned. But how are you meant to cook without a knife? They’ve just started selling pineapple in the shop here , but how do you cut a pineapple without a knife? Or a steak? So you make do. You improvise everything. The fridge is a polystyrene box from the mozzarella deliveries because there aren’t enough chest freezers on the wing for everyone, and your stuff gets crushed or lost if you leave it in there. You adapt. In my family, everyone cooks, even the dog. My dad had a bar near one of Rome’s big theatres and people would come in before the show. Food guides used to mention him back when they were still those thick printed books.

By midday, he’d already made kilos of rosette rolls and industrial amounts of tramezzini. We’d go and pick asparagus or fish together, which is still my big passion. I fish from the shore, the Spanish way. It’s a proper sport. My dad was a huge reference point for me, although the person I’ve listened to most in my life is probably Patrizio, my brother. He’s never done anything dodgy, but he knows how to handle himself on the street. He’s got a showroom where I work as a warehouse guy, and sometimes I cook for his clients. I studied cooking, even the chemistry of it. And now I adapt all of that here. Because food in prison means something different. It makes you feel a bit like you’re at home. It’s the moment of the day when you feel the least alone. There are no celebrations in prison. Holidays are a disaster. You don’t even celebrate birthdays. It’s weird if someone does. You hardly even tell anyone when it’s your birthday. In here, the only thing you celebrate is freedom. But you laugh. You laugh a lot. You have to, in a place where all you hear about are days, permits, requests, forms, and how shit everyone feels.

When I first came in, I was forty-two, and my son was three months old. He’s four now and comes every Monday. I did a year, then got house arrest for a few months, and in the end came back to prison. That first year, I barely saw my son, Giulio, maybe three or four times. I don’t even want to think about it. But in those first three months before the arrest, we were like one person, inseparable. I’ve got 7 nieces and nephews, became an uncle at six, so when he was born, I already knew how to change nappies, how to wash a baby. I was more practised than my wife, who was learning it all with him. And I wanted that child so badly. We were inseparable.

But I know prison is something that never leaves you. You never shake it off. Whether you do a day, a week, or a month, you never forget it.

The first time I ever played football with Giulio outdoors was here, in the green area at Rebibbia, which is also the only park I’ve taken him to so far. But he doesn’t know this is a prison. We haven’t told him, and I don’t think he’s worked it out because he doesn’t even know what a prison is. He thinks his dad is working to take him to Euro Disney and has to stay here. And every time he comes, he tells me I need to come home and that he doesn’t care about Euro Disney. Coming here is a fixed appointment for him; he looks forward to it. If during the week he gets upset or feels someone’s treated him badly, he tells his mum, “I’ll tell Dad on Monday.” I’m a cool dad; we play loads when he comes. After a couple of hours, he gets tired, and I get a bit of time with my wife. And you know, she and I are madly in love.

Visits at Rebibbia are only during the week. Giulio’s still in nursery, and I’ll be home in a year, but other kids have to skip a day of school every week to see their dads. If visits were on weekends, it’d be so much easier, also because those are the quietest days inside. And Sundays? You can’t even make phone calls. It’s when your whole family would be together for lunch, but you can’t call. Sunday is the emptiest, longest day here. But I never think about time inside. There’s only one moment when I notice it: at night, when they shut the door. In the cell, we watch a bit of telly, then I put in my earplugs, kiss my photos, and turn the light off early. That way, another day ends quicker.

As for the rest, I don’t think about it. Prison has to be taken head-on. But I know prison is something that never leaves you. You never shake it off. Whether you do a day, a week, or a month, you never forget it. Bad things don’t fade. You know, maybe you forget the laughs you had with your mates, but the bad things? How do you forget those? And I’m sure that when I see something terrible on the outside, it’ll bring me straight back here, where I’ve seen it all. Everything will bring me back here.

Giuseppe

In conversation with Isabella De Silvestro

I work in the tailoring shop here in Rebibbia. I didn’t know how to do anything to begin with—a bit of cross-stitch, nothing more. But I learned, and they even gave me a diploma. I take in trousers, fix collars, repair tracksuits. But I also make top-grade jackets, overcoats, smart suits, sportswear, and high-fashion pieces. We made a beautiful black, made-to-measure coat for the governor, for example. Every year we put on a fashion show. We held the last one out in the green area, putting up a stage in the yard. A jacket like the ones we make here can cost up to 2,500 euros. The last one I made is going to a Tunisian lad. They’re all hand-stitched, using quality fabrics like cool wool or silk. I’ve even built up a wardrobe of my own: coats, jackets, bombers. All made by me. And I wear them proudly. Take these jeans, they’re D&G. Not Dolce & Gabbana, but D’Alessandri Giuseppe. My name!

At first, it was just a way to pass the time, then it became something more serious. Now I can say I can sew well, even better than the master tailor, according to him. He always says I sew straighter than he does on the machine. When he’s not around, I come here to help out and do things for the other lads. I never imagined I’d get into it. I’d always done completely different things: plumbing, electrics, metalwork, carpentry. I’ve always been good with my hands though—they say I’ve got golden hands.

Us prisoners made that reform happen by rioting and smashing everything.

Using a sewing machine takes precision and a lot of patience. And you need plenty of patience to do bird as well. I’ve been in Rebibbia 12 years straight now, but if you count my whole life, I’ve done 38 in total, and I’ve still got time left… My first stint was in a young offenders’ unit at 14. They waited until I was old enough to be charged, then they put me inside. It was 1972, before the prison reform of ’75. Us prisoners made that reform happen by rioting and smashing everything. And because me and three or four others were wild, at 15 they moved me to Rebibbia, which at the time had a juvenile wing. I practically inaugurated this prison.

After another riot, they sent me to L’Aquila. I escaped. They caught me and moved me to Potenza. In Potenza, they tried to rape me. I smashed a window to defend myself—I’ve still got the stitches in my hand. From there, I was sent to Volterra with the political prisoners, the Red Brigade lot. They took four guards and a brigadier hostage. I got a commendation because I told the officer, “We’ll watch the guards,” and I kept the situation under control without hurting anyone. After that, where did they send me? Lucca. And who was in Lucca? The governor of the prison I’d escaped from as a minor. He said, “Giuseppe, what are you doing here?” “Eh, gov’…” I said, “I’m in for this, this, this, and this.”

I could tell you so many stories… Like the year I did in a Spanish jail in the nineties. Just after being brought in, in the storeroom with the sheets and all that stuff, they gave me three condoms. I didn’t get it. I took them and pushed them away. The guard brought them back. I pushed them away again. I said, “Signò, I’m not maricón, eh!” And he goes, “Guagliò, we have the hour of love here.” Swear to God, and he said it in Neapolitan. I couldn’t believe it. There, even 30 years ago, conjugal visits were a right—a room, a bed, a bathroom. If you want to kiss your wife or make love, that’s your business. It’s normal, it’s human. I conceived my fourth child in one of those rooms. One day we’ll get that here too, but it’ll take time.

With all the time I’ve done, I can definitely say prison has got worse. There’s no staff anymore; the numbers just aren’t there. I’ve seen terrible things. I saw three suicides one after the other in my wing. It feels like we’ve been abandoned, and the guards can’t take it anymore either. They’re running from one wing to another, and if something happens, the poor sods can’t keep up. This place will ruin your health nowadays. Lately, I lost thirty kilos, I had a tumour, then an aneurysm. I’m doing a bit better now, but I had to rebuild my whole wardrobe—my trousers were falling off me from how thin I’d got. Thank God for the tailoring shop, which has sort of become my kingdom.

I’ve even become protective of the place. I want everything in order, and I want people to respect the tools. It’d be great to involve more lads, but it’s not easy. Many start the course and have to drop it straight away because as soon as they find a paid job, they take it—which is normal, we’re all broke in here. We need some kind of incentive, so the classes don’t empty out. I suggested making ties and selling them to keep us going, or sewing gowns to rent to the lawyers in Piazzale Clodio. But these projects struggle to get off the ground. In the meantime, I spend my days here. And every now and then, a little bird comes to visit me at the window. I crumble up a snack, and he comes right over. He’s not scared of me anymore.

Daniele

In conversation with Federica Delogu

My name’s Daniele, I’m thirty, and I’ve got two kids who are my whole life. One’s four, the other’s twelve. I’ve been in Rebibbia for two years. When they arrested me they brought me here, then after two weeks they sent me to Viterbo because the place was overflowing. I came back soon after when I asked to be moved closer to my kids, because they’re disabled. Now I see them every week with my partner, and once a month my mum and dad come too. Only once, because five people can only visit once a month.

I think I came into prison at a bad time. I mean the system itself: overcrowded, not enough staff. That means delays in reports, long waits to speak to anyone… There are too few of them, too many of us. A month ago, I moved from a six-man cell to a double, and now I’m in with a mate. I got on well with the lads in the old cell too, but you know what they say: a double cell is half a prison sentence. We’ve got three spaces: the bathroom, a little kitchenette, then the room with the bed, the telly, and the lockers. It feels more human.