“In the end, the reward I expected in return for the wrong I had suffered was impossible.”

Sergio did not die that day. He came close, terrifyingly close. But he did not die. A miracle, for many. Not for Sergio, a man of the twentieth century, that age of maximal expansion of technique and reason, which had already—as Horkheimer and Adorno argued as early as 1947—so swiftly and dialectically inverted into its own negation. Something of the Frankfurt School must also have reached the four people who, that morning, decided to come to his studio and tear the life from his bones. It was a morning in May 1980, the long weekend for International Workers’ Day was approaching, and Sergio was about to leave for Umbria to visit a friend. By eight o’clock, he was already in his studio, picking up a few papers to take with him. The doorbell rang while he was on the phone with his brother, first at the main entrance, then at the studio door. Sergio opened without hesitation, believing it to be his secretary, who was supposed to be helping him with some work. For an instant, he wondered why she hadn’t used her keys but immediately reassured himself that she must have forgotten them in the rush. He opened the door. A foot entered, then a shoulder. It was not the secretary but four individuals: three men and a woman. Sergio Mutti, Maurice Bignami, Ciro Longo, and Giulia Borrelli. All members of Prima Linea.

They gagged him and tied him up quickly, having noticed the receiver resting on the table and realising that his brother had heard everything. Sergio did what he could to slow them down, making clumsy movements, resisting physically, hoping that someone might arrive. But no one did, and the four dragged him into the bathroom: “I was thinking of the doubly miserable fate that had befallen me: to die, and to die with my head resting on a toilet.”[1] They fired. Sergio fell to the ground, bleeding so heavily that a warm rush filled his mouth and loosened the tape gagging him. But he did not lose consciousness: the bullet splintered his skull but did not penetrate. It would remain lodged there for the rest of his life. Though conscious, he had no strength to speak. In that moment, he was nothing but an inert mass of flesh, with a single, unbearably painful point at the base of his skull. He was in a state of total vertigo, whirling “in an infinite space, weightless”[2]. In the years that followed, he learned that a second shot might have killed him, but one of the attackers, Longo, deeply shaken by what was happening, had aimed badly and the bullet merely grazed his hair. A second miracle. Not for Sergio, a man of the twentieth century.

The group left, but not before scrawling a message on the wall to make clear why they had come: “Annihilate the technicians of counterinsurgency.” Sergio was indeed a “technician”, and the four members of Prima Linea were there that morning to kill him and steal documents relating to the prison of Spoleto, which he had designed. Sergio’s surname was Lenci: he was an architect, a university professor, and a civil servant at the Directorate General of the Institutions of Prevention and Punishment within the Ministry of Grace and Justice, the section responsible for managing the ministry’s real-estate assets: judicial prisons, youth detention centres, and criminal asylums. He joined in 1952, straight after graduating. By then, Sergio, Neapolitan by birth, was living in Rome, where he would remain for the rest of his life, forming a curious and entirely involuntary bond with the Via Tiburtina, the ancient consular road he would travel again and again, moving between building sites, court hearings, and meetings, in search of an answer to a single question: “Why me?”

In 1949, Sergio joined the design group working on the Tiburtino district for INA [social housing project by the National Insurance Institute] (near Via dei Fiorentini), alongside Quaroni, Ridolfi, Gorio, Lugli, Valori, Fiorentino, and others. The work never quite convinced him, prompting long reflections on the relationship between form and function in architecture and on solutions being developed in Northern Europe. Once appointed by the Ministry, Sergio began visiting various prisons, an experience that marked him profoundly: “When I visited one of those infernal dwellings for work, I felt almost ashamed to leave; I felt a kind of unease, as though the freedom granted to me were some sort of privilege. I sensed the despair and degradation of the inmates and felt that, in their eyes, I belonged to the forces of power that deprived them of their liberty.”[3] Overcrowding was already a problem, as was the nature of the buildings: fortresses, convents, and palaces repurposed for detention; old, damp, decaying, and barely maintained. Sergio, a man of the twentieth century, made a list of problems and solutions: “As an architect, the gravest problems that I identified were: the lack of air and light; the high humidity in crowded spaces with no ventilation; total promiscuity amid already unbearable overcrowding; the constant background noise, punctuated by shouts, curses, calls, orders; the unbearable smell of bodily emissions of all kinds, and of mould, cigarette smoke, frying garlic. […] Primary needs: clean, bright, airy, easily cleaned interiors; the need for vegetation in contact with the buildings, reducing the fully walled and paved nature of outdoor areas; the need to increase the distance between building façades.”[4]

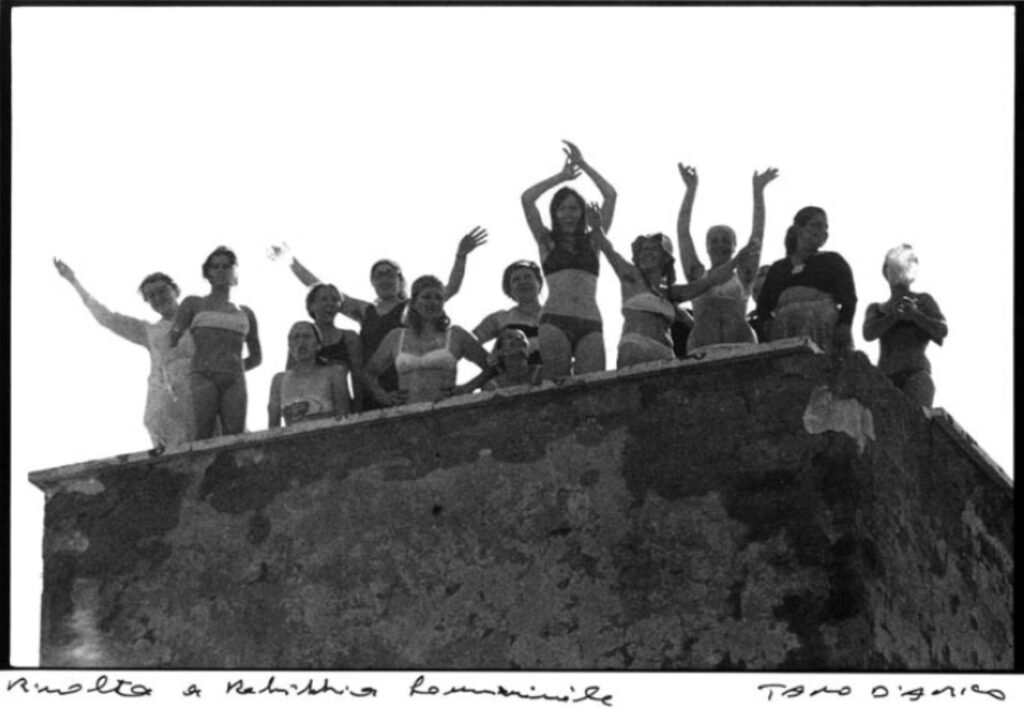

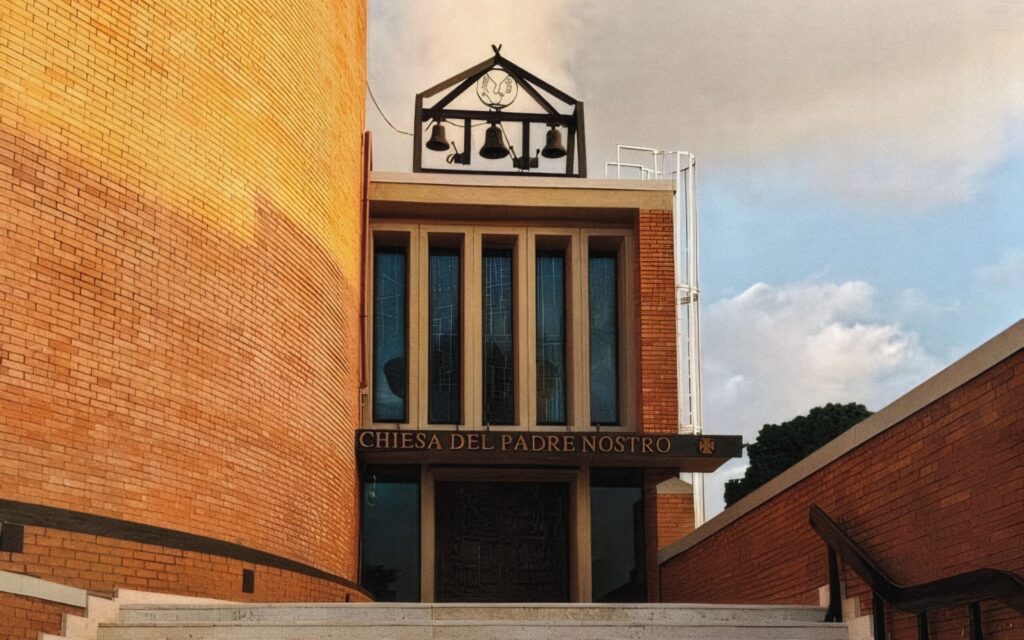

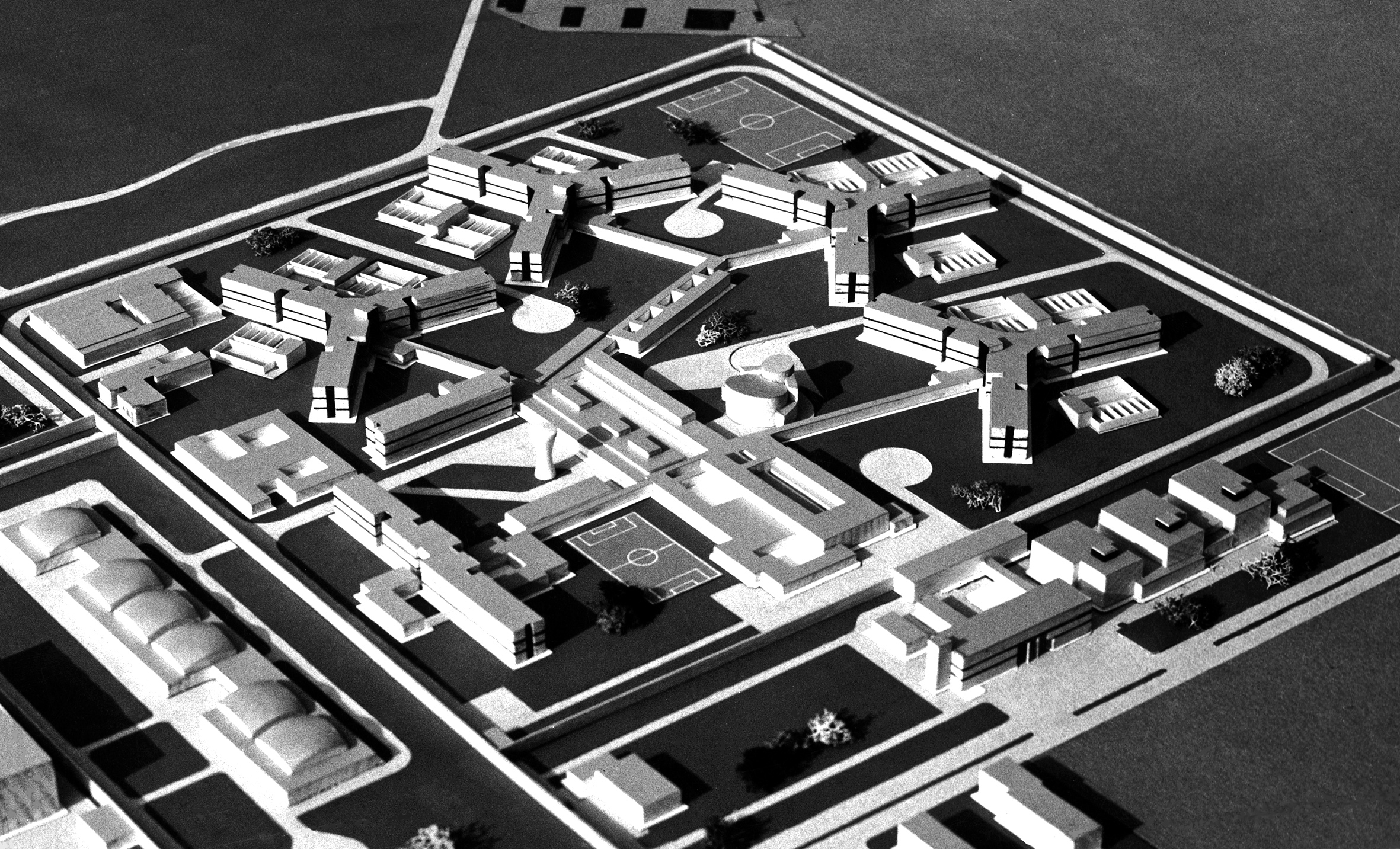

The chance to give form to these ideas came in 1959, when he was asked to present a design for a new complex to be built in Rebibbia, once again along the Via Tiburtina. Two buildings already stood there: the women’s prison, which had replaced the old Mantellate in Trastevere, and the men’s penitentiary. They were the legacy of a Fascist-era plan from the late 1930s: the idea of a penitentiary city that would sit alongside other ‘cities’ of the regime—the university city of La Sapienza, the military city of Cecchignola, and the E42 exhibition city at EUR. It was a monstrous project by engineer Luigi Asioli, Head of the Office of Building Works of the Civil Engineering Corps in Rome, conceived for more than 6,000 inmates, with church, administration, and kitchens at the centre, and work and housing arranged around them. The “three Fs of good government: force, festivities, flour (administration, church, kitchen)”[5]. Sergio’s ideas ran counter to all this, and were a direct consequence of the scientific progress that he had witnessed firsthand: “Today, medical science, psychiatry, psychology, social sciences, and even legal studies have established that individuals who deviate from the norm are driven by a series of causes, and that in many cases these causes can be identified and removed, so that the individual, with appropriate treatment, can be reintegrated into society.”[6]

From confinement to treatment, from exclusion to reintegration, with architecture tasked with shaping the forms and spaces needed for such a process: “Architecture must not be an instrument of torture, but an interim solution, a transition, a mediation towards other possible solutions linked to entirely different social structures.”[7] So out go the walkways. Sergio rejected the idea of single blocks over several floors observed from a central vantage point; he preferred separate buildings of three storeys, with closed floors and basic services organised autonomously for small groups of inmates, with spacing that allowed for better light and ventilation. Three-armed star-shaped pavilions, connected to a central structure of communal services. He cited three sources of inspiration: the inmates’ buildings derived from visits to Danish university campuses; the internal zones housing central and collective services drawing on Alvar Aalto; and the external areas, for administration and prison officers, taking cues from Le Corbusier and Italian Rationalism. An open structure with differentiated circulation and access for different functions and groups—mediation being the key word—with spaces designed to offer psychological relief through the scale of rooms, access to views, proper sanitation facilities, sports amenities, and abundant greenery around the pavilions.

“Architecture must not be an instrument of torture, but an interim solution, a transition, a mediation towards other possible solutions linked to entirely different social structures.”

For some, it was, paradoxically, too much. Sergio was not one of the most popular professors at La Sapienza: he was neither a sympathiser of the Movement nor among the compliant lecturers who gave out marks at mass student assemblies. He recalled being frequently challenged, especially by a group known as the Uccelli. In the 1970s, universities were a porous membrane through which the Movement slipped into the armed struggle and vice versa. Sergio was certain that his name had reached Prima Linea through those channels. Indeed, some years later, in a hideout in Ostia, several pages on Rebibbia from Prison Architecture, a 1975 volume he had edited following a UN-commissioned study, were found, having been stolen from the Architecture Faculty library: “The terrorists saw in that study the opposite of what it contained: not a search for progress, but a reaffirmation of the prison, and perhaps even propaganda in favour of increased incarceration […] I might have resembled the symbol of a State that still builds prisons.”[8] A reformer who defused a conflictual tension that “worse detention conditions would have made more heated”[9]. It was the morning of 2 May 1980, and someone knocked on the door.

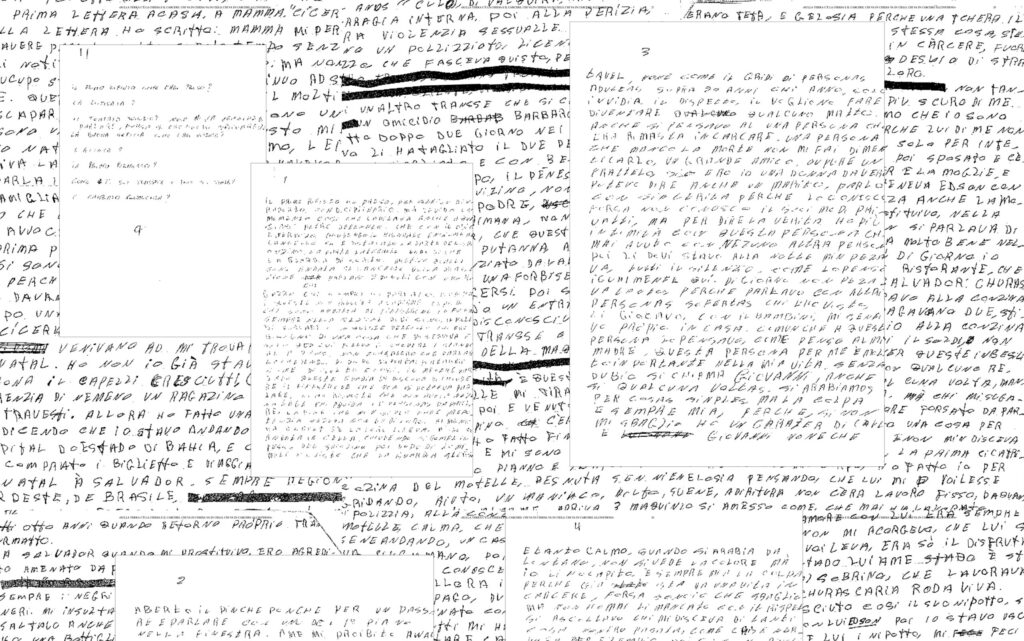

Sergio took a long time to recover, but eventually the damaged nerve endings healed, the bone fragments held in place, and the bullet stayed put. A new battle began: the battle for truth—both judicial truth and the truth of ‘reason’. Once again, he found himself travelling the Tiburtina over and over. The trial took place in the bunker courtroom at Rebibbia, where he felt more alone than ever: “Another surprise: there were only two civil claimants. One was the IACP of Rome, the other was me. The ministries and the Municipality of Rome were absent, not even represented.”[10] Not even the Order of Architects spoke up. A solitude bordering on the quixotic: Sergio read everything published on terrorism, wrote letters, intervened in public debate, and above all, in attempting to make sense of what had happened, followed the trail of names, networks, money flows, and political cover for a design far larger than its executors.

Eventually, invited by Father Bachelet—brother of Vittorio, murdered by the Red Brigades in 1980—he met his attackers in person, repeatedly: Borrelli in Bergamo, Bignami and Mutti in Rebibbia (on the Via Tiburtina yet again). Intense encounters, powerful ones, but all ending in the same unsatisfying way: reflections on their crimes, yes; sincere political discussions, too; but no truth about why, at a certain point in his life, Sergio had become a “symbol of evil”. He, a man of the twentieth century, an ordinary servant of the State, a socialist wholly absorbed in solving the problems of the present and rejecting the distant horizons of ideology that fracture and exclude. He, who had taken a bullet for improving penitentiary buildings, only to find himself in the middle of a national debate on pardons, amnesties, political documents, and prison-reform proposals advanced even by former militants of the armed struggle, now imprisoned. Distinctions between terrorism—to be condemned—and terrorists—to be forgiven—because an entire generation could not simply be discarded.

Sergio writes of forgiveness in analytical terms: how it shifted over time from a social issue, eliminating the logic of retaliation (an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth), to a purely personal and spiritual matter,

None of this convinced Sergio. In one of the many letters he wrote to Borrelli, he urged her not to be too self-indulgent, because the sorrow of detention and the deprivation of affection—she had become a mother in the meantime—could not be considered a true sentence, a genuine payment of one’s debt to society, if one remained within a cone of shadow made of silence and convenience. Shadows could no longer exist: for him, that bullet had been a bolt of lightning, a blinding light that had placed him on another plane: “My impression was that with that shot to the back of my head, the game was over and I had now entered the realm of serious, real, authentic things.”[11] In his memoirs, Sergio writes of forgiveness in analytical terms: how it shifted over time from a social issue, eliminating the logic of retaliation (an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth), to a purely personal and spiritual matter, because the collective dimension had been taken on by the State and by a law equal for all.

Is truth the only ground on which victim and perpetrator can meet? Is reintegration possible—the very reintegration Sergio had hoped for and tried to support with his architectural ideas—without engaging the spirit?

Is it possible to go beyond a concept, that of prison, which Sergio himself had called “unacceptable”[12]? To imagine a solution other than the endless chain linking arrest to sentence, through detention, investigation, and trial, in which deviance is instead managed directly by the population within the social, civic, and urban fabric, without resorting to separation, without condemning people to erasure and invisibility? Is any of this possible without a willingness to open oneself with empathy to the other? And can the purest empathy be understood as a precondition of social harmony, a natural remedy to deviance? Sergio, that “sceptical and reformist”[13] man of the twentieth century, spent his endless journeys up and down the Tiburtina searching for a higher, different horizon—one he realised he remained captive to, just as the four who changed his life forever on 2 May 1980 remained, for him, prisoners of their own ideology: “I know that the bullet you lodged in my head did not provoke that leap forward in human relations that I had imagined, just as the weightless evolutions in a soft, immensely luminous space that I experienced when the bullet entered my head were only sensations caused by impact, not an acquired ability to fly. In the end, the reward I expected in return for the wrong I had suffered was impossible. Now I know that life does not offer such escapes, and that it is within its complex and ambiguous logic that one must continue either to navigate or to sink.”[14].

[1] Sergio Lenci, Colpo alla nuca, Il Mulino, Bologna 2009, p. 27.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Sergio Lenci, L’opera architettonica 1950-200, Diagonale 2000, p. 56.

[4] Ibid., p. 56-57.

[5] Sergio Lenci, Una esperienza di progettazione: il carcere giudiziario di Roma-Rebibbia, in “Rassegna di studi penitenziari”, n. 2, marzo-aprile 1968, Tip. Mantellate, 1968, p 188.

[6] Ibid., p. 192.

[7] Ibid., p. 204.

[8] Sergio Lenci, Colpo alla nuca, Il Mulino, Bologna 2009, p. 51.

[9] Ibid., p.137

[10] Ibid., p. 61.

[11] Ibid., p. 155.

[12] Sergio Lenci, Una esperienza di progettazione: il carcere giudiziario di Roma-Rebibbia, in “Rassegna di studi penitenziari”, n. 2, marzo-aprile 1968, Tip. Mantellate, 1968, p 192.

[13] Sergio Lenci, Colpo alla nuca, Il Mulino, Bologna 2009, p. 157.

[14] Ibid., p. 158.