“In images, more than in words, we must look for the stories of the defeated.”

The first time Tano D’Amico entered Rebibbia prison, he saw a young man in a vest, doing small cleaning jobs near the entrance. They told him the man was there for minor offences. Years later, Tano was shocked to find him in exactly the same spot, serving the same sentence. He realised that what kept him inside was not the gravity of any single act but the endless accumulation of small offences that had become a life sentence in all but name.

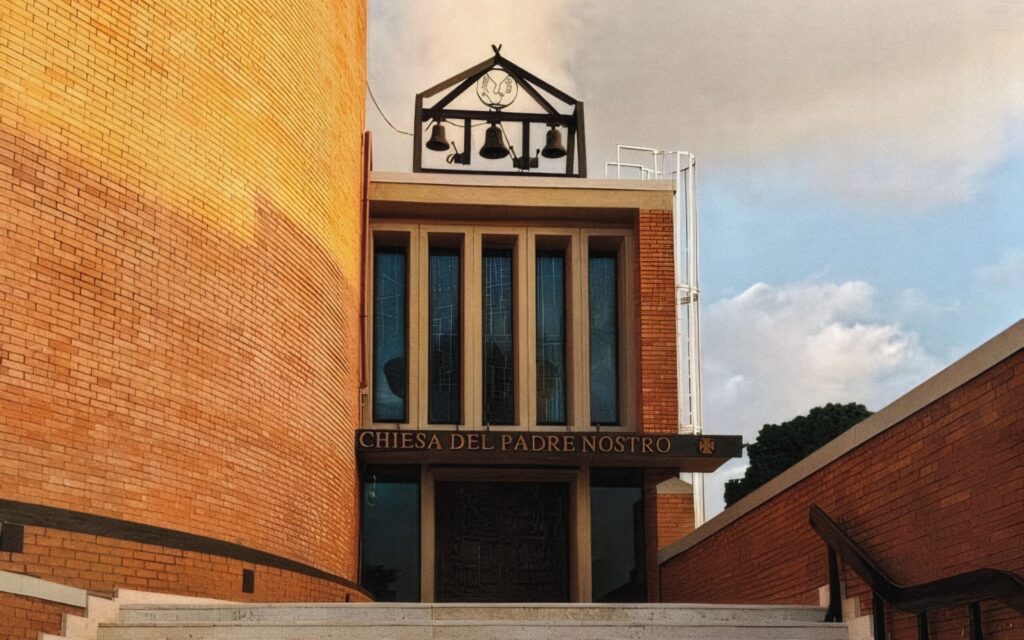

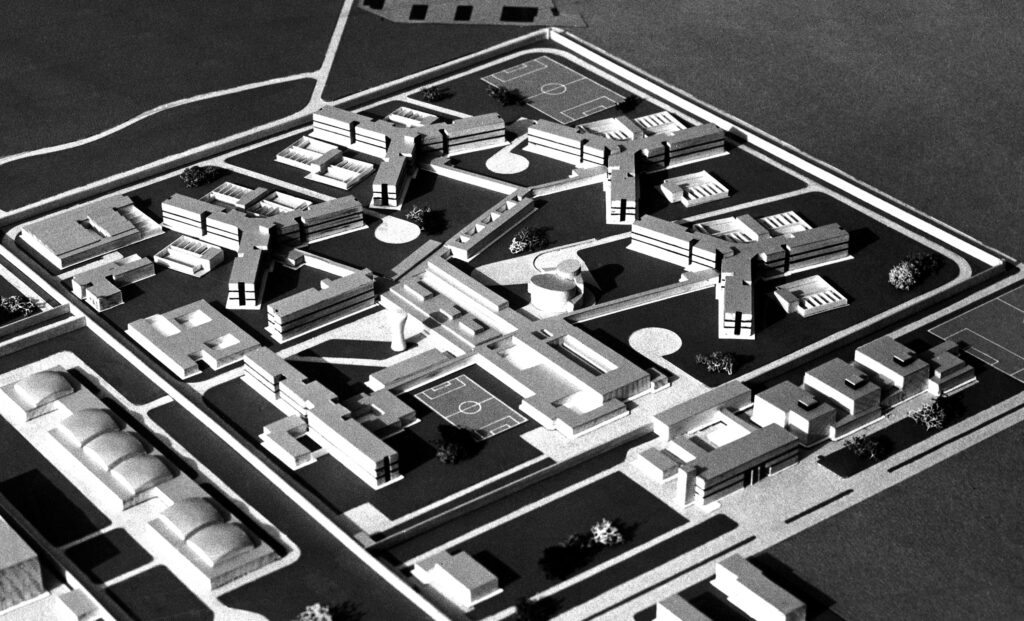

He had come close to those prison walls years earlier, during the revolts of 1973. Back then, he recalls, there weren’t even toilets, only buckets where excrement accumulated at night and was emptied the following morning. In June of that year, the men detained in Rebibbia climbed onto the roofs to protest their living conditions. Tano stood below with his camera. It was a physical and political refusal of any position of dominance or visual detachment, a choice that would shape his approach from then on. While the bodies on the roof defied gravity, occupying a space outside the normal order of imprisonment, he remained among those looking up, sharing their tension and what was at stake. The prison wanted them motionless and invisible; they moved and made themselves seen. Tano’s photographs, etched into the memory of many, revealed the imbalance between the weight of concrete and the fragility of a human equilibrium pushed to its limits. It was then that he decided to follow them more closely.

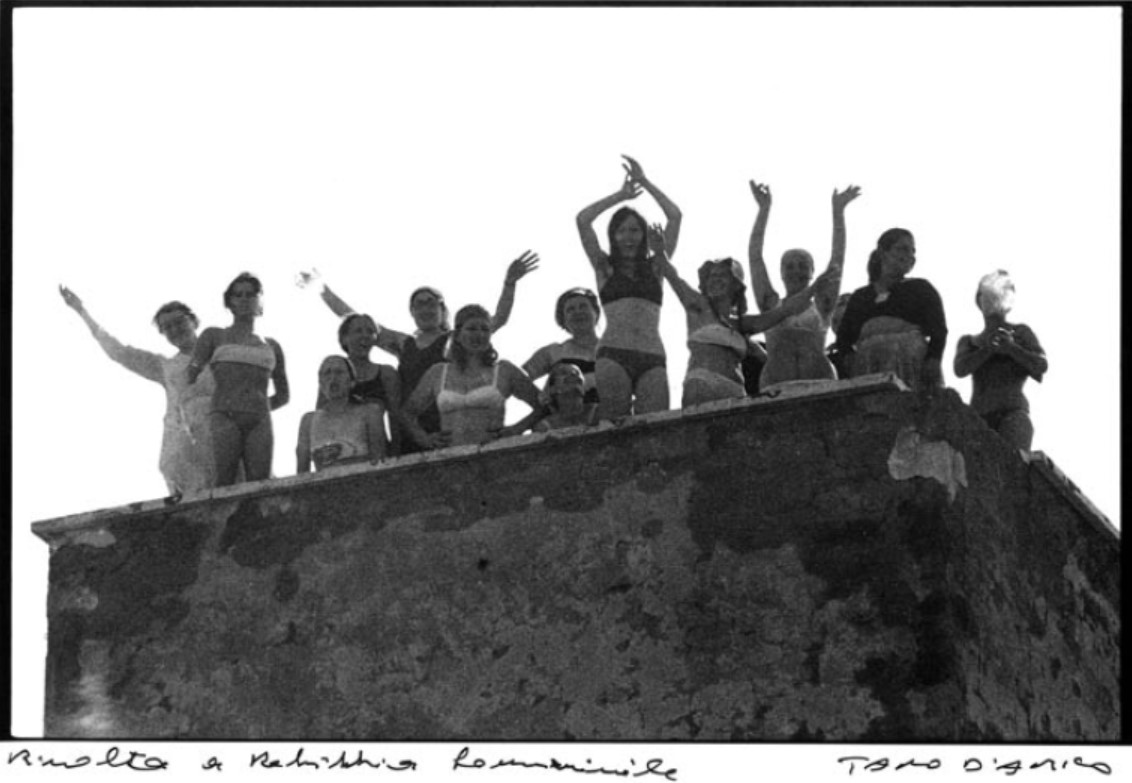

Rows of police and carabinieri made communication almost impossible. What struck him most were the women: wives and girlfriends gathered on a small rise, trying with the tiniest gestures to reach those inside. He remembers a hand opening slowly, almost in slow motion. Only a few days later, a revolt erupted in the women’s section of Rebibbia. From afar, using a 600 mm lens borrowed from a colleague, he captured women of all ages, in swimsuits or fully dressed, who stared into the lens with their arms lifted to the sky. Those images still circulate today. They have become symbols of women’s determination to say no, to say enough. There is no photography without a position, and Tano D’Amico’s has always been the same: alongside people. Not in front, like someone who judges; not behind, like someone who follows; but side by side, as close as possible to faces, lives, and struggles—to those he calls “the dissatisfied”, and, for that very reason, alive. It is a gaze that lives on the margins and urgently leans outward from there to give visibility to what would otherwise remain unseen.

His relationship with the prison did not end in those years; in fact, it had only just begun. Some time later, Tano was asked to lead sessions inside. “Do you mind if I send you the ones who’ve been here the longest?” asked the director at the time, hinting at complex psychological situations. “That’s why I’m here”, he replied. And so, every Monday for years, he crossed those heavy doors, never allowed to bring books or a camera. The guards, however, turned a blind eye when they noticed the art postcards hidden in his pockets: images of masterpieces used as a pretext for dialogue. The “students”, initially inert, were also prompted by certain “accomplices” who assisted Tano, prisoners tasked with challenging him and getting the discussion moving. If he missed a Monday, his return was met with long faces: a clear sign they had been waiting for him.

In prison, deprivation always intertwines with unexpected gestures of care. One prisoner, convicted of serious offences and barred from the benefits available to others, began chasing after him with plates of fried eggs when he discovered that Tano skipped lunch to make the most of his allotted time. The women teased him affectionately, “What kind of man are you, obeying these orders?” And so, every Monday for three years, Tano sent faxes of protest to the Ministry about the restrictions he faced. No reply ever came. Until one day, authorisation finally arrived: for one day only, he would be allowed to bring disposable cardboard cameras.

With no funds to work with, he obtained the warden’s blessing to approach Kodak. The next day, at Rebibbia, the cameras disappeared within hours. Men and women took photographs non-stop, not even reading the instructions—exactly as he had planned. Among the vivid memories that remain, Tano recalls above all a woman obsessively photographing a rose just centimetres from the lens. Attempts to explain that the camera could not focus at such close range were useless: she simply carried on.

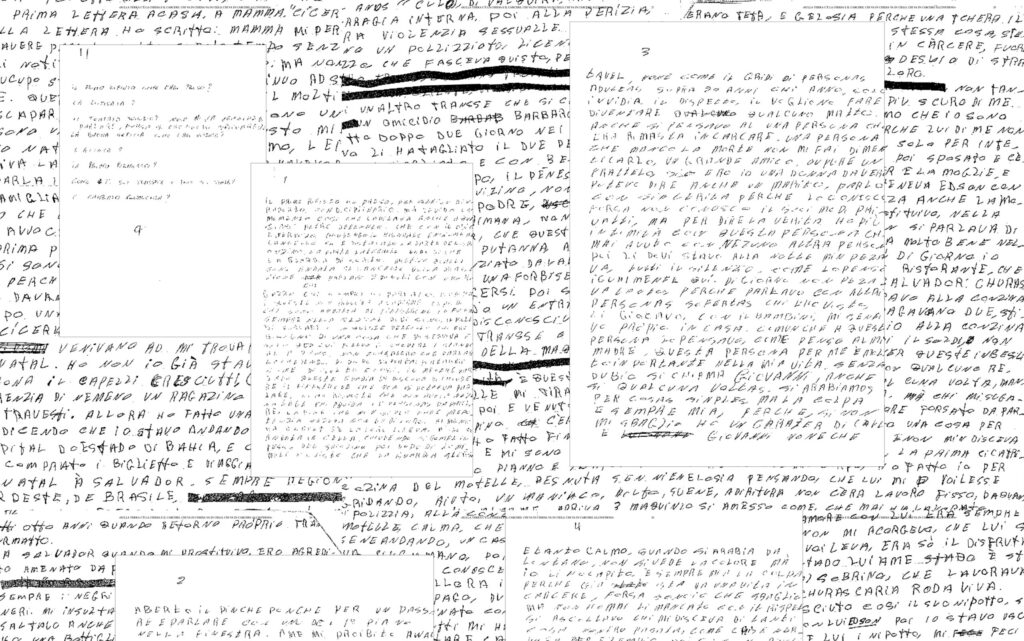

This was how the Camera Oscura workshop came into being, led by Tano: a way to overturn photography’s usual role from an instrument of control and transform it into a space of shared freedom, and above all, a way to bridge, or at least narrow, the distance from the outside. As some participants wrote years later: “Since we do not wish anyone to have to come and visit us here, we prefer to reach you ourselves through our images.”

A way to overturn photography’s usual role from an instrument of control and transform it into a space of shared freedom, and above all, a way to bridge, or at least narrow, the distance from the outside.

When it came time to develop the rolls, the results surprised him: the images did not resemble his own but those of Luigi Ghirri, whose work he had often discussed with the prisoners. With his walls, skies, and enclosed horizons, Ghirri seemed to speak more directly to those who could no longer see their own.

Thanks to the invaluable help of Gianni Borgia, then Rome’s councillor for culture, summoned by Tano in the middle of the night, the films were developed and printed. Those photographs formed the basis of an exhibition at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni. A success, but one that carried unresolved questions, especially about what still remained in the shadows. Liliana Scarpelli, one of the participants, wrote: “I don’t understand why they forbade us from photographing bars and gates. Are we or are we not in prison? […] Could it be that visitors to the exhibition might feel ill at ease knowing that we live behind these bars?” A similar question was posed by Franca, another prisoner who, complaining about restrictions such as the ban on showing certain spaces, asked “What is the point if no one, except those who have lived and live in such a confined space, where everything smells of iron, will ever understand how grey this reality is?!”

On the day of the opening, a coach brought the prisoners into the museum. At Tano’s request, they guided the visitors themselves through the images they had taken and the words they had written. Afterwards, they all ate pizza together, a simple, unrepeatable celebration. Among the photographs, one stood out: an explosion of red petals, “like an atomic explosion, but of love”, that rose which, for Tano, remained “one of the most violent images I have ever seen”.⁴ Radio3 honoured it with readings and songs about roses. The Italian and international press covered the event. The Corriere della Sera newspaper even ran the headline “Kodak behind bars”.

His path inside Rebibbia had begun with “Gattabuismo”, a painting workshop devised by Pablo Echaurren in 1996. It provided a space for play, creation, and imagination within the prison, with Tano acting as reporter. But unlike those who later took part in his own project, he notes that the men and women involved had not lost their sense of life. With “Camera Oscura” in 1999, the experience became more radical: photography was no longer an external act of observation but a collective process, a voice returned.

For Tano, telling the story of the prison has never been a neutral act. If prison photography began as a form of identification, a bureaucratic distillation of guilt, here it opened a breach: “In images, more than in words, we must look for the stories of the defeated, the persecuted, the humiliated, the wronged. Words have often pinned them down. They have condemned them.”5 Words, he says, belong to the powerful, whereas images belong to everyone. They live in the space before thought, like poetry or dreams. They require no explanation, only that you feel them.

One day, he asked the man who shared his meals why he cared so much for him. The man replied, “Because your images remind me of my mother.” Yet he had never known his mother. It was the idea of a mother that he gleaned from the photographs. This, perhaps, is Tano D’Amico’s most radical lesson: photography can redraw physical and social spaces and create conversations even where none should be possible. It can transform the prison—a place of deprivation and invisibility—into a horizon of possibility. From the hills of 1973 to the improvised classrooms of the workshops, the camera offered not only documents but processes, not only images but relationships. And in the stubborn gestures of those who, from inside the walls, raised their arms to the sky or photographed a rose, the greatest thirst remained: to be seen, heard, recognised.

A fragile, stubborn hope that resembles his photographs and those of his students: images, he says, cannot be stopped.

Rebibbia has changed, he says, now inaccessible compared with before, as if that small hill from which he used to watch and photograph the rooftops had vanished. When, at the press conference for Camera Oscura, he was asked about the future of the project, he expressed his wish to go out into the neighbourhoods of Rome with the prisoners, to meet the men and women of the city, the soul of its culture. But that was the last time he was invited. From the way he tells it—from the vivid, emotional clarity of his memory—it is clear that in reality he never left. Initiatives such as Scatto Libero, a Roman association led by Tania Boazzelli with a group of photographers and enthusiasts, show how the path opened by Tano D’Amico has continued.

His memory returns to that young man at the entrance. Always there, guilty of little, yet crushed by an endlessly renewed sentence. In him, Tano had seen the paradox of prison: the disproportionate weight of accumulation, which crushes even the smallest act. Yet at the same time, as in the rose photographed to exhaustion, as in the bodies on the rooftops of Rebibbia—fragile yet resisting—as in the hands slowly opening towards the sky, in that young man Tano continues to glimpse an opening, a possibility. A fragile, stubborn hope that resembles his photographs and those of his students: images, he says, cannot be stopped.

All quotations are taken from Camera Oscura: immagini da Rebibbia, Arcisolidarietà: Associazione Ora d’Aria, 1988.