An Untold Story: The Journey of Live Arts from Its Origins in Bologna

Where does the focus on a sensitivity attuned to the boldest contemporary challenges in the performing arts originate in Italy?

When we talk about live arts, that is, “arts performed live,” what are we referring to? Imagine, for example, John Cage’s Train, a work commissioned in 1978 to the great American artist for the second edition of the International Performance Week in Bologna. A railway convoy that, as it crossed the Italian countryside, transformed into the stage for a day-long artistic action based on pre-recorded music. Every station, carriage, and sound produced by the train, its passengers, and the surrounding landscape became part of the ever-evolving composition. Blending the mechanical rhythm of the rails with the unpredictability of environmental sounds, a vivid and irreproducible symphony emerged—a sonic journey celebrating organised chaos and the interaction between humankind and the environment; an happening, an event transcending the boundaries of music and performance.

To answer the initial question, we first have to acknowledge that even today, in everyday communication, we tend to simplify by mostly referring to theatre, dance, and music—art forms that are indeed live. We also talk about visual or multimedia arts when they involve a specific relationship with the audience’s presence, or even cinema when it becomes a real-time participatory event. We use the umbrella term performance, which has become pervasive and, as a result, increasingly less effective—often as a catch-all label for “that thing” we experienced but can’t quite categorise.

The thing is that, in live arts, all of these categories coexist in proximity to the vibrant concept of presence—the liveness. Around the latter, in direct or indirect ways, depending on the participatory gradients employed from time to time, the arts connect, blending and overlapping, dissolving their boundaries.

The thing is that, in live arts, all of these categories coexist in proximity to the vibrant concept of presence—the liveness.

However, the result of this hybridisation doesn’t correspond to the sum and coexistence of the specific disciplines in a mutual dialogue—the so-called multidisciplinarity—but rather to another artistic creature, another phenomenon. We could call it a “vertigo” of the performative, borrowing the words of Germano Celant from an exhibition he curated under the same name in 2007 at the Museum of Modern Art in Bologna: “It results in a vortex,” stated the great art critic, “that engulfs every experience and everything, in which all elements of artistic communication enter into a complex system that is irreducible, multifaceted, and circular, within which it is impossible to determine a hierarchical organisation.”

If, from this standpoint, we want to hypothesise some trajectories for a “secret” history of the live arts in Italy, then we should probably start from Bologna and, more broadly, from Emilia-Romagna. Over the last fifty years, thanks to a cultural humus often favourable to experimentation and contamination, the regional capital has played a central role in bringing into focus, in our country, an awareness attuned to the boldest challenges of contemporary performance. In particular, this was achieved through a unique coexistence—albeit sometimes conflictual—between institutions and culturally discordant entities, which made Bologna, until very recently, a truly special hub in Italy.

This story finds a seminal moment of synthesis precisely in the chain of events that characterised the International Performance Week starting in 1977. After nearly a decade of youth activism that had deeply traversed and shaken Italy and Bologna itself, the ‘77 Bologna movement, with its components of political radicalism and creative euphoria—with the University occupied and the Living Theatre in the streets—provided the unique backdrop for the first of six editions of the event, curated until 1982 by Renato Barilli, Francesca Alinovi, and Roberto Daolio. These three figures managed to create a dialogue between the various facets of art and the worlds of criticism, artistic production, and, not least, academia.

Indeed, we shouldn’t forget that DAMS was established in 1971 in Bologna as the first degree in Italy entirely dedicated to the interaction between arts, music, and entertainment disciplines. This project was built on an innovative approach to higher education, incorporating the contributions of researchers, intellectuals, and artists. Among others, Eco, Maldonado, Pignotti, Scabia, Leydi, and Celati were involved. Barilli, Alinovi, and Daolio also worked within and around the DAMS laboratory in its early days, in a trend for which—quoting the title of an exhibition they curated in 1981 as part of the fifth edition of the Settimana—“all the arts tend towards performance.”

Even the most advanced instances of the New Theater and New Dance of those years found, in Performance Week, a melting point—one that, in some ways, was unique and unrepeatable. This was also thanks to the collaboration of the curators with the two critic-gurus of the time, Franco Quadri and Leonetta Bentivoglio. The "electric" body of Laurie Anderson, or the naked bodies of Marina Abramović and Ulay, facing each other and in contact with the visitor in their historic Imponderabilia, ideally mirrored the iconic charge of "theatrical" realities such as Il Carrozzone by Lombardi-Tiezzi-D’Amburgo and Gaia Scienza by Corsetti; or in the cold, deconstructed choreographies of Simone Forti and Steve Paxton, "stars" of that American postmodern era that had stripped the body of any dramatic rhetoric.

Still in Bologna, there was the Neon Gallery, where, since 1981, Alinovi and Daolio’s vision had found refuge in an eccentric mix of performative and conceptual experiments, or those sentimentally aligned with the nonconformist idea of art professed by its guiding spirit and co-founder, Gino Gianuizzi. Or, though of an entirely different kind, the Cassero, established in 1982 as a space for identity and cultural expression of the LGBTQIA+ community—a nearly unique case at the time, on a national scale, resulting from a virtuous negotiation between a public institution (the Municipality of Bologna) and an association with an openly homosexual orientation.

The “Bolognese model,” or the close relationship between independent spaces dedicated to grassroots experimentation and the city’s cultural fabric.

The list of this narrative could go on, reflecting what Francesco Spampinato recently described as the “Bolognese model,” or the close relationship between independent spaces dedicated to grassroots experimentation and the city’s cultural fabric. With the distinctive ability to develop—according to the researcher—“bottom-up professionalisation models in various sectors of the arts, entertainment, and communication, sometimes in synergy with institutions and local administration, but never dependent on them.”

However, for the story we are attempting to trace here, even if only in flashes, it is necessary at this point to focus on a second, decisive moment of synthesis, which came to light in 1994. This moment emerged both as a long-range outcome of the tensions that had animated the '77 Bologna movement and the years immediately following, as well as the new demands for imagination and change from those who approached the 1990s with an antagonistic spirit. We are talking about the Link Project.

Between the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Pantera generation manifested in Bologna through organised forms of dissent. Fueled by the anxieties of cyberpunk and the rejection of a "capitalist realism" that, as theorised by Mark Fisher, sought to colonise their dreams and the very notion of the future. In a city with the DAMS (Arts, Music, and Performing Arts Studies), which faced strong criticism regarding its ability to still interpret the present, several student collectives occupied the university, creating new genealogies through the self-management of autonomous spaces for education and cultural programming. This period was marked by a series of turbulent occupations, culminating in the opening of cult venues such as Isola nel Kantiere, Livello 57, and, shortly after, TPO. These spaces of aggregation and design aimed to translate, in an alternative way to mass monoculture, the sense of belonging of a new generation and its way of interpreting cohabitation. However, the occupations were followed by evictions and mediation tactics with the city administration, aiming to ensure that the momentum generated by this polycentric and difficult-to-classify movement—including collectives, informal groups, activists, and new creative intelligence—could find a useful convergence point.

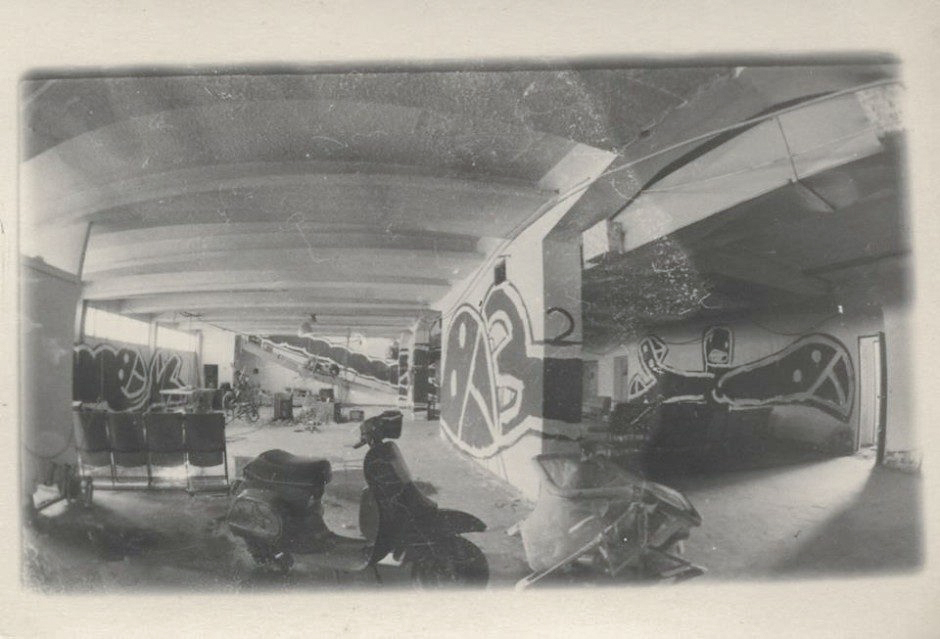

The Link project originates from here, from the encounter-clash between a self-taught and self-sufficient community and the institution’s containment strategies, at the crossroads of a highly diverse galaxy of people who, in various capacities and contact with a similar European network, were involved in video, graphics, web, communication, experimental theatre, cinema and TV, video art, actionism and performance, electronic music and research, historical avant-gardes, and new underground currents.All of this took place in an industrial space that was anything but conventional: a former depot of the municipal pharmacies, near the railway station. More than two thousand square metres of space were dedicated to events and services, operating without an internal hierarchy, except in relation to the capacity to host thousands of people rather than fifty, and thus able to foster different relationships and functions. Three rooms varied in size for live events, but also laboratories, a library, a bar café, an internet point, a basement, and spaces for discussion.

Starting from the space and its functional and imaginative peculiarities meant stepping outside the box, putting into action a form of creative development that made the space a co-protagonist of the experience offered. The success was overwhelming.

Those who went to the Link might not have known what to expect in terms of programming, because it meant entering an immersive environment, a flow of imagery, a sort of permanent intermedial rave.

Those who went to the Link might not have known what to expect in terms of programming, because it meant entering an immersive environment, a flow of imagery, a sort of permanent intermedial rave. Seamlessly, the same evening could connect the audience with a concert by Aphex Twin or Pan Sonic, a performance by Motus, an exhibition by Pietroiusti; a video dance showcase or a film series dedicated to Bill Viola with a DJ set by Hell. In short, it was a densely packed and high-quality schedule, mostly designed to make accessible what was otherwise not present in Bologna and Italy. It was not a social centre, but rather a genuine (counter)cultural factory of international scope, where political ambitions were concretely transformed into a multi-faceted proposal driven by positions of radical experimentation.

Nowadays, it's almost impossible to capture in just a few lines the complexity generated by the Link Project and the somewhat model-like effect it had on future occupied spaces. However, if we pause to consider the issues surrounding performative and live arts, we must acknowledge that, for approximately six years, something remarkable took place there—largely driven by the blunt figure of Silvia Fanti, who from the beginning was accompanied by the equally strategic and blunt presence of Daniele Gasparinetti, the project's "ideologue."

Both key figures in the DAMS occupations mentioned earlier, as well as in the forms of self-management and counter-cultural programming that emerged from them, they were co-founders of the Link Project along with other comrades. They had tenaciously built the conditions for something that we now recognise as an innovative approach to curatorial management in Italy at that time. Fanti's choices, in particular, extended beyond the Link’s undeniably disruptive programming, placing themselves on the same level as the artistic dimension being summoned. He actively encouraged and shared ideas, creating new contexts for interaction and relationships with the city, and exploring new forms of audience engagement. This sense of responsibility significantly influenced the emergence of new performative languages.

Open, magical, and raw spaces—bare environments that laid bare the skeleton of theatre and dance, where objects, devices, images, and living beings were on the same level.

What was always questioned was the idea of a sclerotised "theatre," with its recognisable rituals, its specific times and dedicated spaces, and its more or less sacralised forms of working on the body, the text, and the narrative. Recently, Fanti recalled how, back then, there was a need for "open, magical, and raw spaces—bare environments that laid bare the skeleton of theatre and dance, where objects, devices, images, and living beings were on the same level."

It’s no coincidence that the Link Project became, during those years, the privileged interlocutor for a new wave of artists on the national scene. A space for co-design and dialogue for those from the previous generation who, in the words of Roberta Ferraresi, "tried to look beyond themselves, beyond their habits and clichés, even engaging in cross-fertilisation with other knowledge, disciplines, cultures, and the more restless areas of the arts and society." In this perspective, for instance, Corsetti, Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio, Teatro Valdoca, Virgilio Sieni, Loredana Putignani, Antonio Neiwiller, Enzo Cosimi or Roberto Castello formed an ideal continuum with the emerging Motus, Fanny & Alexander, Teatrino Clandestino, Kinkaleri and MK, extending to the "undisciplined" scene of Xavier Le Roy, Jérôme Bel, Myriam Gourfink or Marten Spangberg.

To explore the legacy of this experience means discussing not only Bologna's recent past but also its present. After 2001, with the closure of the Link Project and the dispersal of its various elements within the cultural fabric, not only of the city, Fanti and Gasparinetti renewed the challenge under the banner of live arts, through a new, successful, and always independent project that still goes by the name of Xing. It is primarily thanks to the tireless work of this organisation, now involving new collaborators, that Bologna has become even more firmly established on the most authoritative radars of performance art.

This is a story that we believe has inherited, at least symbolically and in suitably updated ways, the heroic season of the International Performance Week, thus contributing to accelerating the metabolism of the 'new' in Italy. To grasp the sense of this silent revolution, it would be enough to take a look at the countless artists invited and supported over nearly twenty-five years of activity, as listed on the Xing website. Their projects include Netmage, F.I.S.Co., Live Arts Week, Raum, and the most recent Holes and Xong. These design modules, on various scales ranging from micro to macro, have repeatedly been innovative and entirely unconventional modes of research, creation, and audience engagement, in diverse and highly significant spaces within the city, “for their location and for their transformative impact on the territory.”

In conclusion, if Rome and Milan today have peaks of excellence in live arts programming, it is partly due to the history of Bologna that has been recounted here. For example, in Rome, one can think of the Short Theatre festival (currently directed by Piersandra Di Matteo) or the Buffalo project (directed by Michele Di Stefano), or the past year's series at the Mattatoio curated by Ilaria Mancia. For Milan, on the other hand, one might consider past experiences like Uovo or the current intention of the Triennale to systematize a "theatrical" programming increasingly open to disciplinary hybridization (both under the expert guidance of Umberto Angelini); or, still in Milan, the Le Alleanze dei Corpi project (curated by Maria Paola Zedda).

It will not surprise us, then, to find in the upcoming Hyperlocal programming performative spores as disorienting as those delivered by “amphibious” groups and artists such as Parini Secondo, Gaia Ginevra Giorgi, Industria Indipendente, Sara Manente, Kinkaleri, and Jacopo Benassi. It is enough to say that, regarding the former, last year many people frowned upon the latest edition of the New Italian Dance Platform—an institutional project aimed at promoting the best of contemporary dance in Italy—expecting "danced" dances that, fortunately, never materialized.