A story of sonic subversion: the breakcore in Brixton and San Vitale

In the volume-drenched darkness of 90s European rave culture, breakcore emerged as a vorticist rhythmachine—driven as much by the centripetal force of sub-bass and the infectiousness of syncopation as by the excitement of pure chaos and distortion.

It’s a common misconception that the more extreme fringes of a musical style—its noisier, most radically ferocious interpretations—emerge from a desire to deviate, pervert, or corrupt the genre’s basic premises. To the average music enthusiast, infusing an established canon with noise and layering it with dissonance is seen as distorting it, a sign of profound disrespect towards its pioneers and their efforts.

More often, what happens is the opposite, especially in electronic music. When genres become harder and noisier, it’s often because a new generation has come around, longing to recreate the same urge, the same sense of twisted wonder and adventurous danger that attracted them to the genre in the first place. It’s a desire to keep the culture alive by one-upping its initial, radical newness.

Such is the case with breakcore: as chimeric and difficult to define as the genre has become, following its unconventional evolutionary path, it originated as an attempt to use chaos and aggression as tools to raise the ante in UK sound system culture. In its earliest iterations, breakcore increased the number of anti-musical elements and mind-boggling rhythmic deconstructions already present in jungle, not to demolish or suppress its groove, but to exponentially enhance its presence and weight. It also drew from the increasingly aggressive distortion and rapid tempos happening in the hardest edges of techno.

Unlike the IDM sect and its (often misunderstood) experiments in abstraction, the first generation of breakcore producers aimed to keep the focus of their free-ranging sonic exploration on the dance. No matter how weird and cacophonic the beats were, it was meant to jolt unsuspecting bodies into motion with a surge of energy. In the volume-drenched darkness of 90s European rave culture, early breakcore emerged as a vorticist rhythmachine—driven as much by the centripetal force of sub-bass and the infectiousness of syncopation as by the excitement of pure chaos and distortion.

If, for the late Mark Fisher, “jungle’s feral geography seemed as if it was derived from dystopian science fiction” and the genre “constructed its own Afro-futurist and cyber-gothic sonic fiction, set in the derelict arcades of a near future,” breakcore arrived to state that the future had come far sooner than expected and that the dreaded dystopia was already permeating every aspect of Western society. The Terminator had been sabotaged, gone mad, and mutated into something grotesque. Dwelling both outside the fortress of the society of control and far from the symbolic confines of the then-consolidated modes of rebellion meant operating at a new level of freedom, experimenting with new ways to dance, interact, and create. It was ultimately a way to keep the true flame of rave alive, despite the already rampant gentrification of dance music.

Breakcore arrived to state that the future had come far sooner than expected and that the dreaded dystopia was already permeating every aspect of Western society.

In the mid-1990s, London was undoubtedly still the promised land for any sect of rave culture, from house and techno to dancehall and jungle’s more popular offshoots like drum & bass, along with their myriad of subgenres. After the infamous Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994 was passed, the city also became home to some highly militant sound systems, constantly organising illegal parties around the M25 motorway. At the time, even legendary crews like Spiral Tribe, who were by then on the verge of relocating to France, had their speakers blasting breaky, noisy, and fast sets that fused the breakneck speed of hardcore techno with the polyrhythmic contortions of jungle. Just a year later, pioneering tribes like Hekate would start pushing the envelope, championing the hardest, darkest, most distorted, and experimental tracks on the scene.

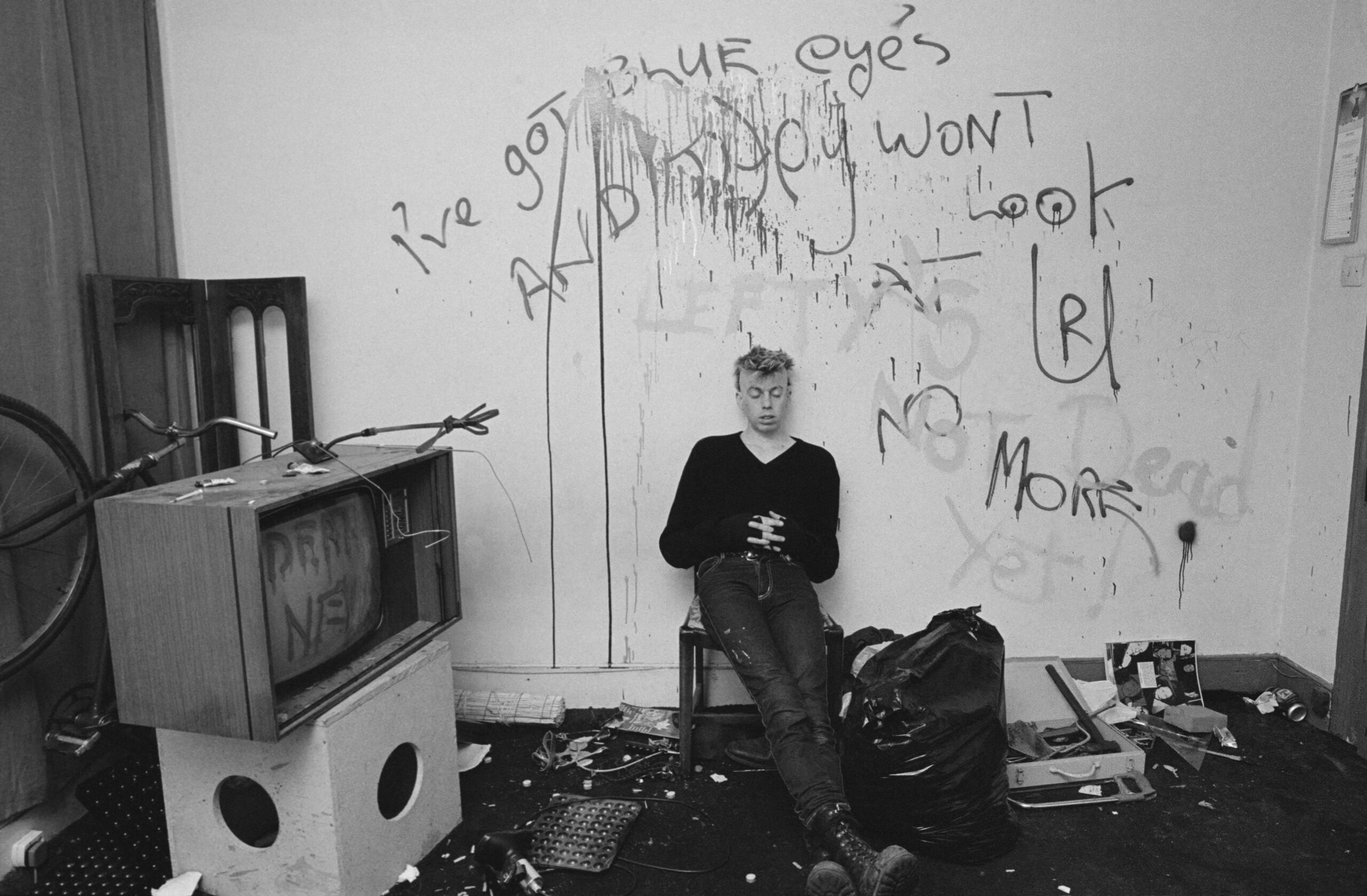

But the roots of the scene were firmly planted in the working-class, multicultural neighbourhood of Brixton. The most radically minded among the crews or individuals who preferred to set their raves in enclosed spaces, rather than in the vast, abandoned warehouses where the tribes roamed, had little access to (and often little interest in) regular clubs. Instead, they preferred to gravitate around the innumerable squats that had taken over South London’s abandoned buildings, repopulating them for practical and political purposes. The DIY countercultural spirit of the radical movement actually served as the perfect backdrop for those who saw partying as a political act, seeking to merge music, militancy and other forms of cross-media cultural experimentation. It was at one of these free spaces—a three-storied Victorian house on Railton Road that a community of anarchists had renamed the 121 Centre—that the monthly Dead By Dawn parties started taking place. That was 1994, and it’s more or less where it all started.

The project was initiated by a collective that called itself The Invisible College, brought together by Swiss musician, DJ, activist and all-out visionary Christoph Fringeli, whose seminal label Praxis had already released its first batch of hard-hitting records. Dead By Dawn was not just a rave, but also a space for political discussions, technological explorations, art exhibitions, and visual installations. Nonetheless, it quickly became known prevalently as home to the fastest, hardest and most radical dance music you could hear in all of London. At the time, this almost entirely meant four-to-the-floor beats. Its residents (DJ Terro, Deviant, Sentinel, and Fringeli himself), along with now-legendary figures that played at those early parties, like Somatic Responses, Sonic Subjunkies, Crystal Distortion, Aphasic and, most notably, DJ Scud, played a mix of noisy gabber, frantic dark techno, and sped-up industrial. If any breakbeats or ragga influences appeared at those early parties, they were met with bemusement, if not outright scorn, by the crusty attendees.

Ironically, the seeds for the contamination between the post-ragga continuum and the noisier side of things were being planted not in London, but in Germany, between Frankfurt and Berlin. It was among the early releases of Achim Szepanski’s Force Inc. label (and its many sub-imprints like Position Chrome, Riot Beats, and Mille Plateaux) that the first 12”s appeared, pushing jungle to its extreme consequences. Most of these records were produced by the same guy: Alexander Wilke, AKA Alec Empire. Born and raised in Berlin, Empire began organising parties in the German capital with the Bass Terror Soundsystem, which he founded alongside vocalist and DJ Carl Crack, and would soon launch his own label, the highly influential Digital Hardcore Recordings. Initially driven by a radical spirit similar to that of Praxis and Dead By Dawn, Empire would eventually aim for mainstream stardom (mainly through legendary band Atari Teenage Riot) and ultimately experience a fall from grace, both artistically and politically.

Influences and records started bouncing back and forth between Brixton and Kreuzberg, eventually expanding into new territories. The scene matured, and by 1996, Dead By Dawn had shifted from being advertised as a “techno speed core party” to promoting “experimental electronics, dark breaks, harshcore.” A key figure in this paradigm shift was the aforementioned DJ Scud, real name Toby Reynolds. A Londoner, Reynolds had also spent considerable time in Berlin, exploring its foggy and—at the time—scarcely populated clubs, and became especially enamoured with local underground star Tanith’s hard-edged and creative approach to DJing.

Reynolds initially started Dead By Dawn just to dance, but as his record collection grew, so did his desire to make those records spin in public and even create his own. All of it would soon become reality. In addition to becoming a regular in the DBD lineups, he began producing and releasing music with the help of another 121 Centre regular, Jason Skeet. While Reynolds adopted the monicker DJ Scud, Skeet called himself Aphasic, and together they founded a label called Ambush, with each release instantly becoming a classic of the genre.

It is no mystery to any breakcorehead how important Reynolds was to the genre, not only by being one of its best DJs and most creative producers, but also by defining it as both creatively unpredictable and firmly rooted in Jamaican dance culture. His approach to music-making was shaped by his regular attendance at the Notting Hill Carnivals, where he was captivated by the marvellous tracks blasting from the massive Caribbean sound systems. He used noise, distortion and experimentation to emulate the awe those tracks generated in him. This led him to develop a distinctly personal sound that evolved and mutated with each release and remains incredibly fresh to this day. The IDM crowd took notice, and in 2003, Aphex Twin decided to release a collection of Scud tracks on his own label, Rephlex.

At Dead By Dawn in August 1995, Scud had a fortuitous meeting that would end up bringing breakcore to a new country. At that party, Toby met and became friends with Riccardo Balli, a young straight-edger from Italy who was then involved in hardcore punk bands, the local noise scene, and running the infoshop at LINK Project, a squatted cultural centre and music venue in his hometown of Bologna. Balli had just discovered breakcore and was galvanised by its potential. In his own words, he had finally found a way “to escape the dead-end of pure noise, which had been stagnating for ages, through funk, not as a musical genre, but as a goosebump that makes your ass shake.” In other words, he had found a means of sonic terrorism and cultural sabotage through a language that communicated with the body first.

Balli had already been in contact with fringes of the neo-situationist movement, such as the Luther Blisset Project in Bologna, but it was in London that he became a member of a radical space-oriented dis-organisation named Association of Autonomous Astronauts, a group also connected with other figures in the breakcore scene. At Dead By Dawn, with its crossover of rave culture, avant-garde politics (often personified by infamous characters like Stewart Home) and experimental anti-art, he found a new home. Soon after, Scud taught him how to DJ, and he quickly mastered the most radical and challenging techniques of turntablism. Riccardo Balli had now transformed into DJ Balli, ready to move back to Italy and introduce the global underground to his unique brand of breakcore “alla Bolognese.”

Riccardo Balli had now transformed into DJ Balli, ready to move back to Italy and introduce the global underground to his unique brand of breakcore “alla Bolognese.”

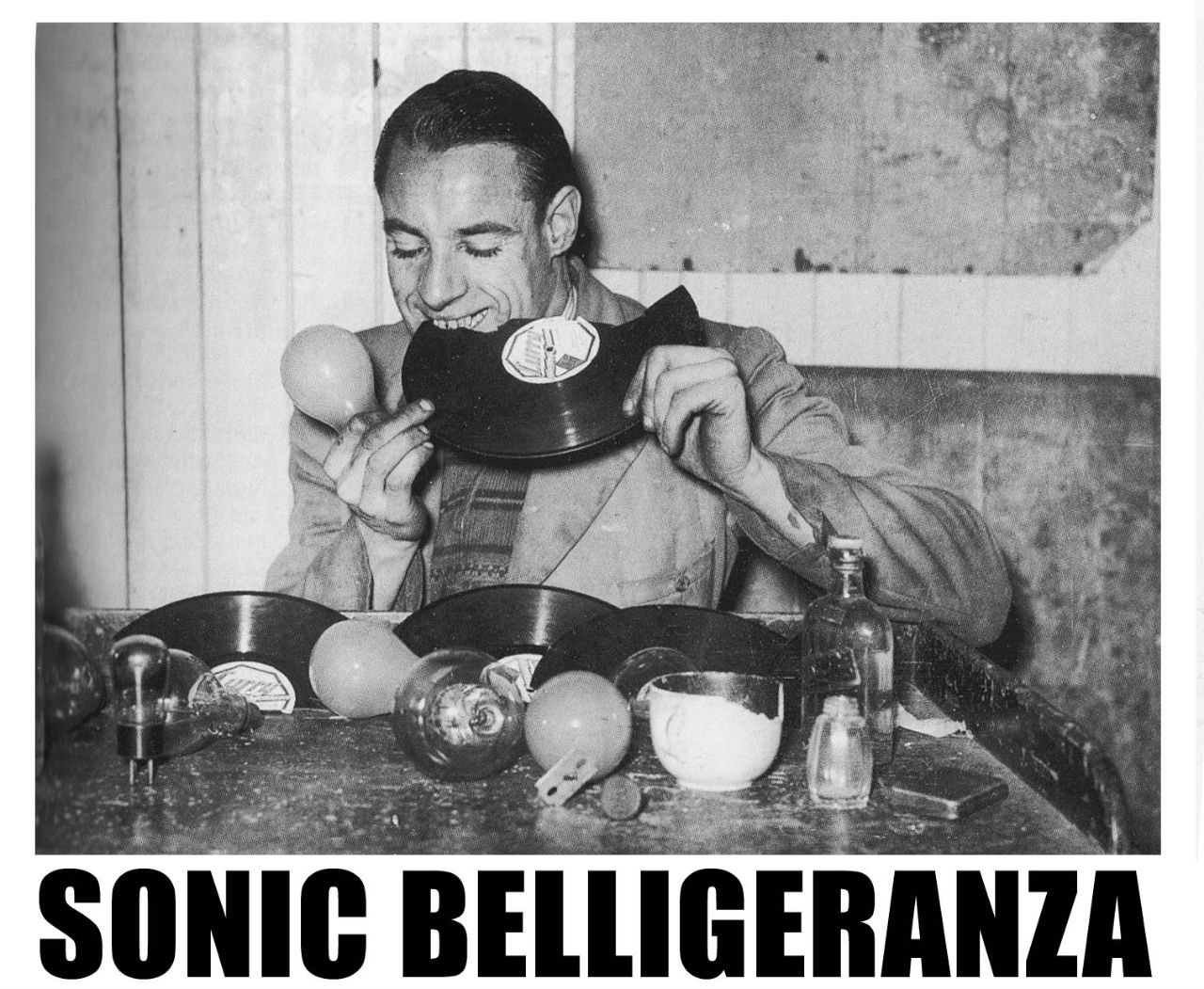

When the genre landed in Italy, a country with a sprawling and intense illegal rave scene intertwined with its counterculture and its radical left, it largely stayed a one-man affair. Balli soon began bringing all of his DBD friends to the Link Project. Then, in the early 2000s, he started hosting regular breakcore parties at the Vicolo Bolognetti cultural centre in the San Vitale district of Bologna. For a very long time, he was the only true champion of the genre in the whole country. By then, he had also launched a label: Sonic Belligeranza, which served as a manifesto for his own vision of what breakcore—essentially, anything. Transcending its more rave-oriented roots and embracing the situationist idea of playful cultural rioting, Balli used breakcore as a vehicle to experiment, deconstruct, and subvert popular culture, turning it into ugly, unsettling tools of mass deprogramming. By approaching each new project with the same radicalism, he helped transform the genre into something both sonically elusive and conceptually hard to define. His vision, while somewhat distinct, also complements Scud’s, creating a cacophony that is not only musical but cultural.

Several generations later, and possibly due to the influence of Balli’s new approach, breakcore has become almost unrecognisable to the older heads. It has passed through the eclectic IDM-like contaminations brought in the early 2000s by artists like Venetian Snares, Kid 606, and Bong-Ra, absorbed the dank influence of meme culture and internet-based trash music, and culminated in a current revival infused with hyperpop elements and manga-inspired aesthetics on one side, and benzo-laden ambient doomerism on the other. For those who know how to identify it, however, the influence of early breakcore, or at least an affinity with its spirit, can still be found in countless artists and genres, often hailing from scenes far removed from the mainstays of European dance music. After all, as one Praxis newsletter put it, breakcore “could be anything that’s not laid back, mind-numbing or otherwise reflecting, celebrating or complementing the status quo.”