Globally and locally isolated: Ursynów and Mokotów as symbols of post-communist subculture in Southern Warsaw

In the early 1990s, as Poland emerged from Soviet influence and rebuilt after the fall of communism, a new subculture began to take shape in the urban blocks of working-class neighbourhoods. Known as blokersi or “kids from the block,” these youth, often from economically marginalised families, embraced hip-hop culture as a means to express their post-communist identity. They used graffiti, skateboarding, and rap music to critique the disillusionment of the era, with southern Warsaw districts like Mokotów and Ursynów becoming the epicentres of this cultural movement. It was here that Polish hip-hop was born, giving rise to influential crews like ZIP Skład, Molesta, and Hemp Gru, marking the start of a unique social and musical revolution in the country.

«The street finds its own uses of things»

William Gibson

One of the main things that struck me when I first started digging into 1990s Polish rap history were the technical limitations producers faced when creating music. As a country emerging from a communist regime imposing strict regulations on import and export policies, foreign goods—namely music records and production tools—were both scarce and expensive. Consequently, the vast majority of first-wave Polish producers could not emulate the US hip-hop production formula, sampling records from funk to disco to soul using an Akai MPC. Given these circulation difficulties, this hip-hop movement had to carve its own way of producing music. From sampling heritage records and soundtracks to producing with haywire computers and cracked audio software, Polish producers laid hip-hop’s identity on raw aesthetics and DIY attitude, with the whole movement kicking off a 10-year delay, compared to the US and Western Europe. These first pieces of information I crossed paths with during my research made me understand how switching from Communist to Capitalist Poland was a day 0 on a timeline, the pivot around which the Polish Hip-Hop movement started. Similar to grime in East London and footwork in the Chicago South Side, it seems like marginalisation and isolation played a major role in this subculture’s self-definition: not being aligned with the technological and cultural innovations of the time provoked a compensation mechanism that evolved into a hyperlocal identity. What’s even more compelling about this “hyper-localised” musical history is that marginalisation did not take place in a suburb or a district inhabited by migrant communities mixing their cultural codes with local ones, like in grime. Instead, it was an entire country under strict borders and autocratic policies.

Yet marginalisation is scalable, working in tandem on both national and neighbourhood levels, as subcultures tend to emerge in localised pockets tied to specific geographies. In Warsaw, these hotspots are found in the city’s southern districts of Ursynów and Mokotów—areas shaped by communist-era urban planning, from Ursynów’s sprawling estates of prefabricated concrete blocks, or blokowisko, to Mokotów’s denser grid of older tenement houses.

A classic of hip-hop countercultural tales, often, structural exclusion produces survival exercises in listening to “the voice of the unheard,” and nothing sets structural differences better than Capitalism. The unheard voices we’re talking about are the blokersi’s, young inhabitants of blokowiska—plural of blokowisko, ed.

«The stairwells of the capital's tower blocks and the courtyards of the tenement houses in the center of the city have finally found their voice.»

Filip Kalinowski speaking about Vienio and Włodi from Molesta, Niechciani, nielubiani: Warszawski rap lat 90.

(Unwanted, disliked: Warsaw rap in the 1990s.)

After introducing and summarising every variable of this hyperlocal phenomenon, it’s necessary to give a brief socio-cultural context of Poland from the beginning of the 1970s to the end of the 1980s in order to understand how the hip-hop movement emerged.

Post-communist disillusionment: Blokersi and the search for identity through hip-hop

Exactly when Public Enemy and N.W.A. were releasing genre milestones, respectively, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold us Back and Straight Outta Compton, topping the US musical charts in 1989 and making everyone aware hip-hop is at least as big as the US if not bigger, that same year eastern Europe as a whole was going through a crucial, transactional historical moment: the fall of the communist regime. When the Berlin Wall was falling, Poland, which had never been part of the USSR but from 1952 had a communist government aligned with Moscow, and consequently under its heavy political and military influence, was at the turn from being the Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa (Polish People's Republic) to becoming a democratic non-communist republic, Rzeczpospolita Polska (Republic of Poland). As mentioned earlier, this fueled a cascade of changes affecting Polish citizens daily. For instance, during the communist era, import and export policies were centrally controlled, especially when it came to Western imports, which were severely restricted. The only way to legally buy international goods—otherwise mainly smuggled into the country—was through one specific shop called Pewex, short for Przedsiębiorstwo Eksportu Wewnętrznego, which translates as “Enterprise for Internal Export”. It will take only a few years after the end of the Cold War for Polish society to be turned upside down by capitalism, as the free market would replace state regulation, flooding store shelves and fulfilling the teenage dream of self-definition through consumer goods.

It’s the beginning of the 1990s when Poland sees the first non-communist prime minister in decades, and Soviet influence is officially dissolved altogether with the Warsaw Pact, ending the military alliance with the USSR. It’s time to rebuild the whole country, and even though the population being freed from Soviet domination seems like a win for everyone, you will eventually find losers: the inhabitants of blokowiska, the blocks. Agglomerations linked to state-owned farms and industry enterprises that served as social housing for state employees and their families. The end of the communist era meant the collapse of these state-owned enterprises, leaving inhabitants of blokowiska without jobs, and too poor to be truly given a chance to upgrade their status as they entered this new era. Soon into the 1990s, capitalism switched the lens through which the population saw society, and the hard worker, symbolically rewarded by the regime, quickly became an outcast deserving of destitution. This switch of perspective can be fully understood through the lens of Janusz Czapinski’s studies, who analyses and defines three different dimensions of social exclusion: structural, physical, and normative, with the first being linked to economic possibilities, the second to someone’s state of health, and the third to personal lifestyle choices. If during the communist era the prevalent form of exclusion was of a normative type—for instance, being an alcoholic not sitting well in the communist society—the main kind of exclusion of post-communist Poland became of a structural type, with structural exclusion, according to Czapinski’s studies, being typically hard to reverse and directly correlated to unemployment. One of the main communities subjected to this kind of social exclusion were the blokersi, young men living in blokowiska.

Blokersi, or “kids from the block,” were the first Polish community to be attracted by and consequently represent hip-hop culture in Poland. A youth subculture often coming from working-class or economically marginalised families, they were part of a creative, lively scene trying to define their own post-communist identity through graffiti, skateboarding, and, later in the 1990s, rap music.

The Polish hip-hop movement built its foundation as a social critique of post-1989 disillusionment, with districts in southern Warsaw, such as Mokotów and Ursynów, giving birth to some of the main rap crews in Polish history.

Stereotypically portrayed by the media and society as uneducated and linked to antisocial behaviour such as crime and drug use, they were widely criticised for failing to meet civic standards—depicted not as people with problems, but as a problem themselves. This so-defined ineptitude was also falling perfectly into the homo sovieticus stigma: poor working-class people left unemployed by the old regime demanding state help, envious of other people's state of wealth, as they were incapable of adapting to the new system. They became some kind of scapegoat representing communism’s social failure, and thus easily demonised by the new political establishment, being at the same time victims of neoliberal shock therapy that followed.

Within this socio-cultural fabric, the Polish hip-hop movement built its basis and narrative as a social critique of post-1989 disillusionment, with districts of southern Warsaw, such as Mokotów and Ursynów, being the epicentre of this first hip-hop insurgence, giving birth to some of the main rap crews of Polish history, ZIP Skład, Molesta and Hemp Gru, just to name a few.

Southern Warsaw is a fertile ground for subcultures

«In consequence of the shift westwards of Poland’s borders after the Second World War, accompanied as it was by massive population movement involving both voluntary and forced migrations between 1946 and 1949, Poland became over 98 per cent Polish and over 95 per cent Roman Catholic.»

Renata Pasternak-Mazur

From the end of World War II to the collapse of the Berlin Wall, Polish society had become as monocultural as it could get, withdrawing from the majority of migration flows and global influences for about 40 years. It seemed that the Poles could only relate to what was happening within their borders. As customary for DIY subcultures, this structural condition didn’t stop hip-hop producers from finding their ways of doing things, enhancing, in hindsight, a definition of their identity during the first post-communist years.

“People had to get creative—using cheap keyboards, outdated computers, and software that wasn’t even designed for music production,” said 2K88, an established producer from the Polish scene. Born before the fall of the Berlin Wall but still very young during the 1990s, Przemysław made his breakthrough in hip-hop as “1988,” his older moniker when he was a producer in the duo Syny. “Hip-hop producers mainly sampled Polish records—old jazz recordings, film scores, progressive rock from the communist era—thus giving Polish rap a very distinct sound.” Although many examples could support Przemysław’s argumentation, since Ursynów and Mokotów are the story’s centre, it makes sense to mention one of the first and most important collectives in Polish hip-hop history: Molesta. Formed in 1995 in Ursynów by Vienio (Piotr Więcławski) and Włodi (Paweł Włodkowski), the hip-hop group is considered one of the first bringing the street flavour to Polish hip-hop—also referred to as “uliczny hip-hop,” a translation of street hip-hop, ed. Their first record, Skandal, released in 1998, is a milestone and turning point for Polish rap, as it is considered a pioneering work for hardcore and real-rap, nonetheless, possibly the most important classic of Polish hip-hop. Depicting raw everyday urban life in post-communist South Warsaw blokowiska—where unemployment surged among blokersi, thus leaving them in poverty and persecuted by the police—through their music and lyrics, Molesta portrayed an urban reality made of anger and hopelessness; the mirror of a generational crisis. Their stylistic signature and approach to rap, so real and relatable, led them to become a hip-hop role model grounded in lived local experiences, rather than a gimmick of the American tropes.

Their capacity to express a place-specific translation of hip-hop culture was not only detectable through their lyrics but also in their music. Even though the New York East Coast hip-hop gritty style references were evident, Molesta drew heavily from Polish musical heritage, for example, by including samples of jazz national composers. If, for instance, we take the fourth and tenth tracks from Skandal, respectively “Armagedon” and “Się żyje”, we can find samples from the classical/jazz fusion group Krzesimir Dębski & String Connection. For those less familiar with Polish musical culture, Krzesimir Dębski is a classical composer, jazz violinist, and film scorer representing a significant and figurative intersection between these three relevant musical areas, in Polish culture and hip-hop sampling specifically.

Molesta and DJ 600V’s production of “Się żyje”, which samples Krzesimir Dębski’s jazz-fusion track Workaholic, represents a striking link between Polish hip-hop and the country’s musical heritage. Vienio later humorously acknowledged the unlicensed sample in “Inspiracje,” rapping, “Sorry, że bez pytania, panie Krzesimirze” (“Sorry for sampling without asking, Mr. Krzesimir”), roughly a decade after the original track. The irony runs deeper: Dębski’s Workaholic—a lively instrumental whose title alludes to an industrious, work-driven mindset—stands in stark contrast to Się żyje’s hedonistic narrative, a raw, street-level chronicle of everyday life, alcohol-fueled nights, and moments of escape. The phrase Się żyje, loosely translating to “That’s life” or “We’re living,” captures a fatalistic yet celebratory attitude: life is full of problems, so you might as well drink, smoke, and laugh with your friends while you can. The lyrics also double as a sonic map of Warsaw, name-checking districts like Ursynów and Mokotów, rooting the song firmly in the city’s lived reality.

Dziś myślę o blantach, sztukach, nie o wojnie

Wszystko w porządku, wszystko kontrolnie

Rano będę leczyć kaca

Co tydzień moja grupa do tego powraca

Się żyje dzieciaku, tak się żyje

Today I'm thinking about joints, money, not war

Everything's fine, everything's under control

In the morning I'll cure my hangover

Every week my group comes back to this

Life is good, kid, this is how you live

«I listened to a lot of jazz, and from jazz I went to hip-hop.»

Bogna Świątkowska, Blokersi 2001

Just like its American predecessor, Polish hip-hop lays its foundation on jazz: sometimes directly, through sampling—as in the case of Krzesimir Dębski’s work in Molesta’s milestone record—and other times more figuratively, as a gateway into its youthful, rebellious form. The latter is exemplified by Bogna Świątkowska, a jazz enthusiast later recognised as the godmother of Polish hip-hop.

An information journalist who travelled around Europe before moving to Warsaw at the beginning of the 1990s, Bogna started working for Radio Kolor in Mokotów, hosting a radio show, Kolorszok, which soon became a fundamental point of reference for the hip-hop community in Poland.

Another pivotal contribution came from student clubs, where the first hip-hop parties took place—with DJ 600V being one of the main promoters of these events, held in venues like Hybrydy and Alpha. In hindsight, these spaces were key to the emergence of the Warsaw rap scene for several complementary reasons. On one hand, these spaces provided young and soon-to-be-famous artists—such as Molesta (then known as Mistic Molesta)—the opportunity to perform for their first time in front of a live audience. On the other hand, they served as early social hubs where active participants, either fans or artists, could gather weekly in the same spaces, begin to recognise familiar faces, and form relationships that helped solidify the scene. Another significant student club was Klub Riviera Remont, located on the border between Mokotów and the city centre. As Hirek Wrona, journalist and co-founder of BEAT Records, recalls in Blokersi, everyone from the Warsaw scene passed through this club. Pioneer hip-hop groups like Kaliber 44 and Wzgórza Ya-Pa 3 performed concerts there that are now considered milestones in the timeline of Polish hip-hop.

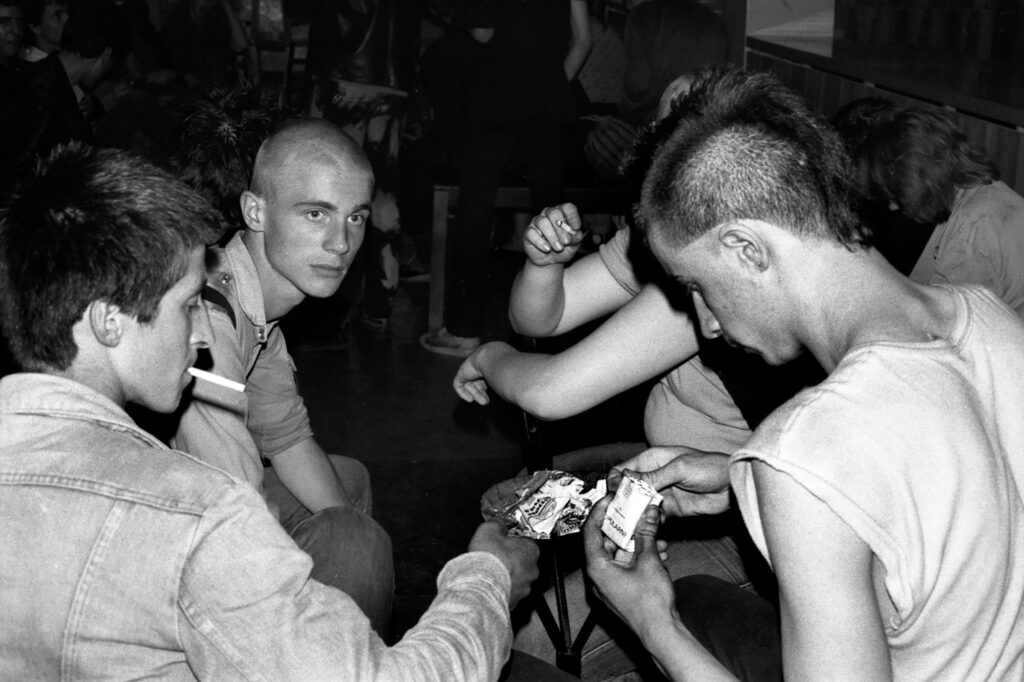

Moreover, student clubs are compelling not only for what has happened there during the rise of hip-hop in the 1990s, but also for what preceded it—offering valuable insight into the lineage of Polish hip-hop. Take, for instance, Remont Klub: founded in 1973, it has long served as a cultural hub, hosting various musical subcultures, particularly punk and jazz. These two styles capture most of the essence of Polish hip-hop, with the latter already explained before, and the first transmitting that anti-establishment positioning and DIY ethics that characterised the movement in its early days. It’s no coincidence that the first rap song ever produced in Poland is believed to be “Nie ma ciszy w bloku,” which translates to: “There is no silence in the block”, by the punk rock band Deuter. If you search for the song on YouTube and browse the comments, you’ll find people claiming that the earliest hip-hop audiences were largely made up of skaters and punks. Early proto-hip-hop concerts were often held in punk venues, simply because hip-hop hadn’t developed a sustainable audience of its own—and the punk community offered common ground. It’s widely known that Włodi, rapper from Molesta, was involved in the hardcore-punk scene, as he played in a band before jumping into hip-hop. This information possibly gives us the last piece of the puzzle needed to frame the genealogy of Polish hip-hop—that missing piece being the hardcore component. Graffiti and skateboarding are practices that not only embrace but, in many ways, demand a hardcore attitude. While graffiti is globally recognised as a core element of hip-hop, skateboarding has been heavily tight with the Polish hip-hop community from its earliest years. For many in the Warsaw rap scene, skateboarding was a first point of connection. It also became a vehicle for cultural exchange: through American skateboarding films and video games in the late 1990s, young people in Poland were exposed to tracks that hadn’t yet arrived in local record stores.

To conclude this chapter on the variables shaping the genesis of hip-hop in Warsaw, it is helpful to turn to a representative case—Molesta, perhaps the most compelling example. Włodi, a skater from Ursynów with roots in the hardcore punk scene, embodied the bridge between these cultural influences and the emerging hip-hop movement in the mid-1990s. Their milestone album Skandal channelled the anti-establishment ethos, rebellious energy, and raw intensity inherited from punk, while at the same time drawing on local traditions through samples of Polish jazz and film scores. All these elements converged in Skandal, allowing Molesta to articulate the frustration and resentment of a generation left without prospects of redemption, yet paradoxically accused of idling on the figurative bench, doing nothing.

«Streets and backyards where “a bunch of drunk punks” sat around all day.»

Filip Kalinowski, Niechciani, nielubiani: Warszawski rap lat 90. (Unwanted, disliked: Warsaw rap in the 1990s.)

Flash-forward: what remains of the Polish hip-hop blueprint in 21st-century globalised Poland? An analysis of TONFA’s project

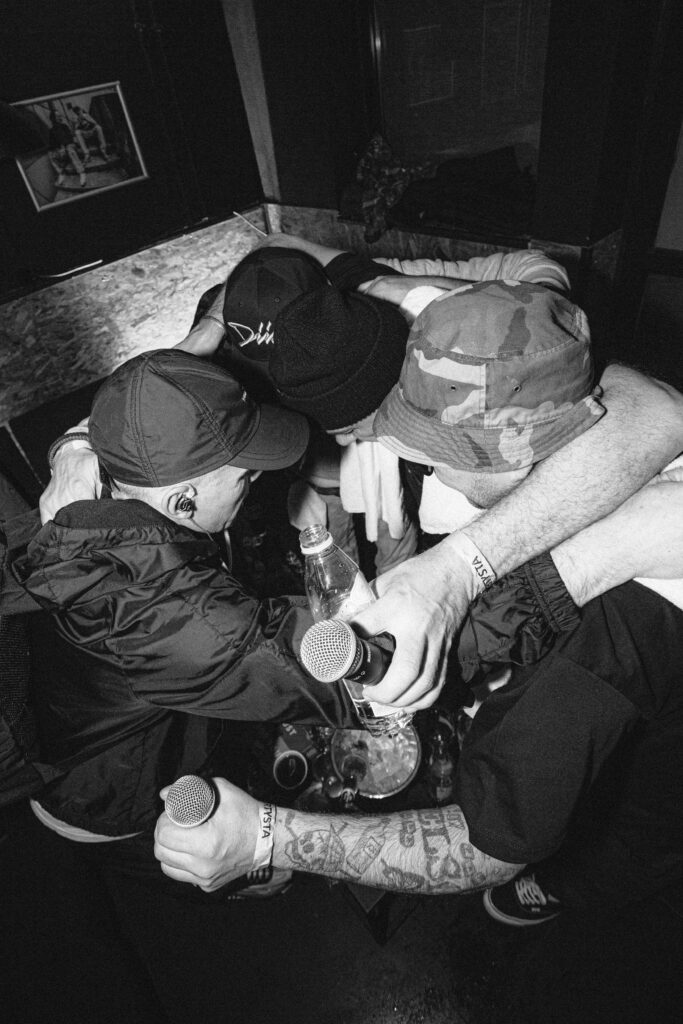

My first intuition about the Polish music scene before I started writing this article was that, in Warsaw and Poland, you could find a niche of artists mixing UK bass music with rap. Soon into my initial research, I could figure that things weren’t exactly as I projected them, even though at the same time I could confirm I crossed paths with an agglomeration of artists doing some sonic experimentation with beats rather than sticking to standardised trap or old school hip hop sounds. One of the first artists I bumped into, who I believe to be representative of this network, is TONFA, a young duo of rappers formed by kierat and Karuzelkaaa in Warsaw back in 2018. I directly got in touch with them to exchange some chats during an early stage of this mini investigation, and quickly into the conversation the duo told me that during recent years “bass” had become in Poland a buzzword for all kinds of promoters in order to label their parties. “You will go to these parties, and you won’t hear bass frequencies because the speakers don’t have subs. You could hear more bass in my car,” says kierat during our call. Even though Karuzelkaaa and kierat cooled down my initial idea of a present scene blending the UK sound with rap, what struck me in our conversation is how many of the variables discussed throughout this article still resonate in TONFA’s music, whether consciously or not. Take the hardcore component, central to Warsaw rap’s emergence in the 1990s: TONFA channels the same raw intensity of hardcore punk bands in their live shows, with a drummer on stage and mosh pits breaking out regularly. The energy they generate is so tangible that even Poland’s hardcore punk community has recognised it, inviting TONFA onto punk lineups and sharing audiences. Out of these encounters grew lasting connections marked by respect, overlap, and friendship: “We played shows with them and we became friends,” mentioned Karuzelkaaa.

When speaking about their approach to music, TONFA—much like hardcore punk bands—embrace a DIY attitude. What sets them apart, however, is their refusal to take themselves too seriously. Hardcore, as they describe it, is “a very serious music,” whereas TONFA infuse their work with playfulness. Whether through wordplay that results in funny punchlines, or by inserting lo-fi audio clips cut from YouTube videos and viral content from Instagram or TikTok—fragments of what you might call Polish internet folklore—their ironic vein distances them from the overtly political tone typical of hardcore and 1990s rap. At the same time, this approach links them to the first wave of Polish hip-hop scene: their method of drawing from local culture feels like a contemporary update of early hip hop’s practice of sampling everyday life. What also brings things full circle—and shows how certain dynamics have persisted—is that Karuzelkaaa first encountered rap when he was youth but really got into it through skateboarding, which still serves as one of the main gateways into hip-hop, just as it did in the nineties. In this sense, TONFA’s path mirrors that of Molesta’s generation, both shaped by the same subcultural channels and the same rebellious drive.

Yet TONFA’s connection to the Warsaw tradition is also tangible on a more personal level. As kierat recalled in an interview with Tygodnik Powszechny, growing up in Ursynów—the same neighbourhood as Włodi—meant sharing everyday encounters on buses and streets, which made the artist seem relatable as a person. This resonance must have been mutual, as in 2020 Włodi invited TONFA to feature on his collaborative album W/88, produced by 1988 (now 2K88), confirming the continuity between the 1990s generation and today’s heirs.

The article now turns to the second artist I spoke with directly during my research: 2K88. In a written Q&A, he reflected on how more and more Polish projects have recently been labelling themselves with the UK Sound—same thing that kierat and Karuzelkaaa mentioned. In response to this trend, Przemysław decided to approach the issue playfully, coining a tongue-in-cheek genre called the “PL Sound.” What began as a joke, however, gradually took shape in his mind. Today, he describes the PL Sound as a fusion of local and global forces: the musical “backwardness” inherited from the communist era, which fostered a stronger identitarian approach to production; the influence of globalisation, as Polish artists increasingly travel—particularly to the UK—bringing new sounds back; and what he calls the Polish musical ethos, marked by coldness, sadness, and nostalgia. In his words, the PL Sound is essentially the UK Sound refracted through this uniquely Polish lens. Still, he is cautious. While he sees this as a useful framework that captures a real trend, he insists that more time must pass—and more artists must be free to experiment—before anyone can claim that the PL Sound is a new artistic movement rather than just an idea in the making.

When hip hop reflects society: from the onset of capitalism to a fully globalised Poland

«Sometimes I try to dig for samples in Polish music because I'm thinking, if I'm gonna steal, I'm just gonna steal from my people, not trying to make it sound like anything else I've heard before. I feel like we're already like super ambassadors of the world, my resource is the world.»

Karuzelkaaa during our first chat

After analysing the conditions through which rap emerged in Warsaw in the 1990s and comparing them with TONFA’s (and 2K88’s) projects, perspectives, and personal journeys, what can we infer about the current state of Polish rap? My take is that TONFA embody a fusion of the core ethos of 1990s hip-hop with new layers shaped by globalisation. Some traits remain constant—the hardcore attitude, the influence of districts like Ursynów, skateboarding as an entry point into hip-hop culture—while others have evolved, with shifts in language, message, and sound that lean toward aesthetic and stylistic experimentation. Their music carries this rebellious Warsaw ethos while sampling Polish cultural heritage—such as early YouTube memes or fragments of internet folklore—and filtering it through global influences, whether absorbed through travel or the internet. In this sense, TONFA inherit hip-hop’s subcultural DNA but express it in contemporary ways that defy easy categorisation. As Jan Błaszczak recalls in Tygodnik Powszechny, the duo once declared on stage: “Not old, not new, not school at all.” It was a statement of intent, rejecting any attempt to reduce their identity to a formula. Of course, one case does not constitute a statistic. TONFA’s trajectory may not reflect Poland’s mainstream rap landscape, where trap and commercially successful acts dominate. Yet their underground stance mirrors that of the 1990s pioneers, making the comparison more appropriate than with chart-topping artists. In the end, TONFA emerge as a fresh contemporary counterpart to Molesta: born of the same cultural “amniotic liquid,” but reshaped by the tools and sensibilities of a globalised Poland.