“If you don’t like your job, why do you do it?”

Despite the evident, at times demoralising challenges of being a bookseller in Italy, and the constant need to refresh shelves where every centimetre comes at a price, it is not unusual to find sections devoted to the political violence that swept the country between the Seventies and Eighties. I don’t believe this is purely for commercial reasons, though the genre certainly has its loyal readers. It is also driven by a form of passion, if not a civic impulse. There are rediscovered classics, strange gems that captivate the diehards, and a steady output from small publishers specialising in accounts of those years. It was in one of those anthologies, whose title I can no longer recall, while researching a project that examined the entire arc of the Red Brigades—from the burning tyres in the Pirelli garages to the televised interview with Curcio, Moretti, and Balzerani— that I came across the tragic death of Germana Stefanini.

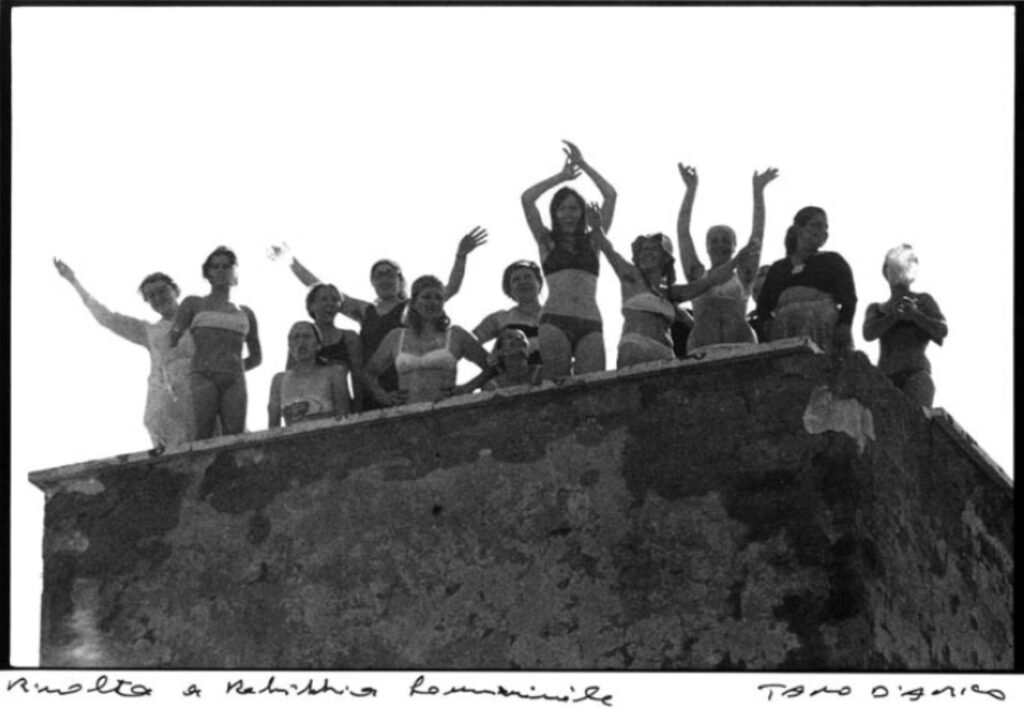

Born in Rome on 9 July 1926, Stefanini had worked in the women’s prison of Rebibbia for less than ten years when, on 28 January 1983, she was kidnapped and killed by an organisation calling itself Armed Proletarian Power. These were the years of a belated psychosis born of the armed struggle of the early Seventies, whose imitators replayed old acts in a completely different context, leaning on derivative jargon stripped of meaning and on social and historical analyses far thinner than their predecessors. Francesco (23), Carlo (27), and Barbara (23) seized her on the landing outside her flat as the nearly 60-year-old Stefanini returned home from work: the only two places she frequented in her life, one to tire herself out, the other to rest. She had taken the job in her late forties thanks to a cousin, a nun, after her father died, and the allowance she depended on for her quiet life on the Prenestina disappeared with him. She lived with her brother Carlo, a plumber, who did not find her in her usual spot in front of the television that evening. The flat presented a small mystery: the door had not been forced, it had been locked. Yet on the kitchen table lay the eggs Stefanini always brought home from the prison coop. Where had she gone?

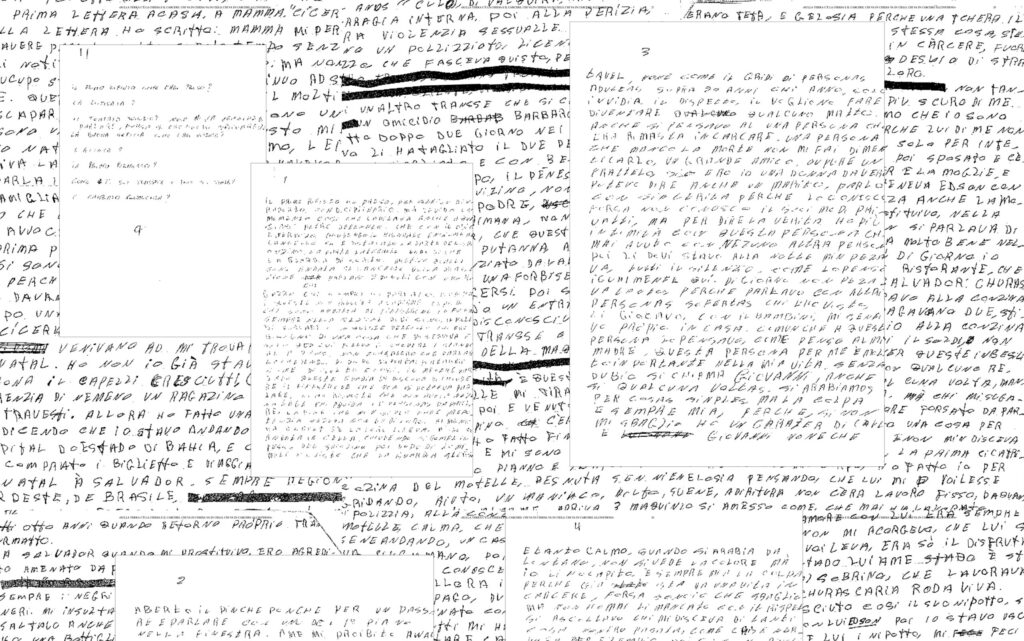

A few hours earlier, the three self-styled revolutionaries had subjected her to a so-called ‘proletarian trial’ in a designated ‘revolutionary tribunal’, or rather, the modest Stefanini living room, where they had hung the Armed Proletarian Power flag. Everything was in place for the customary Polaroid.

The taped interrogation, later found in one of the organisation’s safehouses, is the only element that stirs any compassion for the trio’s colossal ignorance—or at least their complete lack of empathy and any psychological awareness of the person in front of them. The kind of worldly inexperience that only ideology inflamed by desperation can produce.

“If you don’t like your [job], why do you do it?”

“Because when my father died, where was I meant to work? Who would take me at this age? I was supposed to take a job as a maid, but I can’t manage it... I’d have done it if it weren’t for my rheumatic pain, scoliosis, dorsal, cervical, and lumbar osteoarthritis. It’s not like I’m scared of hard work.”

“Explain how you got into Rebibbia, who got you in.”

“I’ve got a cousin who’s a nun. She told me about it because I wouldn’t have to soak my hands all day. And I told her I’d try it.”

“When you said you’d try it, you knew where you were going to work, didn’t you?”

“I’d never set foot in a prison, I didn’t know.”

‘But you were fifty, you knew life, you knew that prisons existed and that they were full of so-called delinquents...”

“Delinquents? Why delinquents? We can all make mistakes.”

The questioning was harsh. Whenever Stefanini tried to build a connection with her captors, they hardened, frightened. Even the vegetable garden got her nowhere.

“Did you supervise the inmates’ work?”

“No, I worked with them, I picked green beans with them, did the packing... I was there with them.”

“Aren’t you kind...”

“No, what’s kindness got to do with it, my love? Look, talk to the ‘politicals’, none of them have a bad word to say of me, they all treat me well... I’ve always treated them properly.”

“Fine, fine, I don’t give a fuck.”

“My love”: Stefanini attempted to connect with the only woman among the three, perhaps instinctively, accustomed as she was to interacting daily with younger women quite unlike her, some easier, some less so. Barbara, like the harder cases, rejected every attempt at connection.

What did they have in common? Little or nothing. The city that hid them, their modest backgrounds, and the smoking. They shared cigarettes: packet after packet, lighters passed back and forth. Stefanini refused Nazionali, so MS and Merit appeared. Twelve cigarette butts would later be found—survivors of 40 years of Italian history—sealed in a transparent plastic pouch closed with a stapler and stored in a file at the Rome police headquarters.

Violence often expresses the urgency of ignorance, and ignorance that of poverty—poverty as a structural condition, political issue, and social responsibility.

Sealed in its own time capsule, the flat on the Prenestina vanished in the haze, filling with ashtrays and floors littered with butts—a detail that alarmed the victim’s brother when he returned home. Perhaps there is only one place left today where people smoke with that same diligence and fervour: the prisons where the three would eventually end up. But first, they had to complete their ‘trial’, declare Stefanini guilty, shoot her in the head, and abandon her in the boot of a Fiat 131.

Violence often expresses the urgency of ignorance, and ignorance that of poverty—poverty as a structural condition, political issue, and social responsibility. These truths are objective, almost universally acknowledged, yet still ignored by much of the political conscience.

Which is why the matter remains in the hands of associations and cooperatives—a world I have come to know closely. Among those serving a sentence or working in restorative justice, the habitual patience and tolerance, the surreal slowness of bureaucracy, can form an alliance with the rhythms of the earth and cultivation—now increasingly alien to the rhythms of production.

It is not easy to discover what a prison garden looks like. The last time I walked out of one—the Giudecca in Venice—I was almost orphaned. It was more than ten years ago. My father had tried to call me while I spent the morning there with other visitors and volunteers during an open-prison initiative. The heart attack was treated, my father remained with his children, and I have not returned to a garden like it since.

These landscapes stay with you because of the stark contrast built into them. The garden at Rebibbia, also a women’s prison, looks larger than the Venetian one in Giulia Merenda’s documentary. Terra Terra takes an hour to explore this green space and the inmates who work it. They hoe, rake, prune. They do what needs doing. Next to the garden stands a greenhouse filled with hundreds of rabbits. One worker inspects them, almost identifying with them: she says that they can make love, whereas she cannot.

Cultivating a garden condenses, within its small perimeter, the millennia of attempts, research, and experimentation that have accompanied sapiens in its strange insistence on the earth—this demand that it provide whatever we choose to eat. This is why garden work feels eternal, as eternal as the cycles governing crop rotation, sowing seasons, and lunar phases. And eternal too is the lazy drag on a cigarette by those locked inside a prison, in the Seventies just as today.

In Merenda’s film, you see women learning the things of the world, from biology to physics. It is not so much prison as the education they receive there that changes them. The director whispers it, but the equation between a person’s culture and cultivation in the field is unmistakable.

Forty years after Stefanini’s death, the woman who killed her—the one who ‘didn’t give a fuck’—gathers the same green beans Stefanini once picked. In recent years, she has moved from high to medium security, gaining the chance to leave her four walls and breathe the air that is everyone’s right. She has not yet found freedom, but she is now permitted to tend the women’s prison garden at Rebibbia, named in honour of Germana Stefanini.

The tragic nature of Stefanini’s story is frightening and archetypal because, like all true tragedies, it does not age and it remains urgent. It is the tragedy of those who live on five or ten thousand euros a year—or little more—and end up losing their hold on things. Reality slips away, abandoning the poor to their anger. Fruit and vegetables, instead, tether us to the reality of Brother Sun, the daylight that illuminates us, beautiful and radiant, in all its splendour.