An “authentically local scene” born in the isolation of London’s East End: Grime, the sound of collective resilience

The history of grime transcends music per se: it’s about economic disparity, racialization and violent urbanization; it’s about the police and the government antagonizing communities originating from geographies of poverty and deprivation. But this is also a heartbreaking story of resilience where music is the medium through which a community, consciously or not, created more space in response to the claustrophobic pressure of the city it inhabited. Born and raised out of isolation in the East End, specifically in Bow (E3), this is a brief recap, proving that a music genre rarely gets more hyperlocal than this. The quoted part of the title comes from chapter three of Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime: a book written by journalist and long-time hardcore fan Dan Hancox, presenting an in-depth socio-political analysis of the East London music phenomenon. For anyone who finds the following account compelling, I suggest diving directly into the text, which provides most of the information within this article. But for now, let’s start from the basics.

Like any other genre that made it to the mainstream, grime is known worldwide thanks to a handful of artists: Skepta, Stormzy, Dizzee Rascal and Wiley. But what did grime sound like before its commercial success, when it was first produced? Afrofuturistic unwanted child of the UK Garage movement, it’s a darker version made by people who weren’t cool enough to get into the polished and dress-coded UKG parties. Too raw to get in, just like the genre sonic palette, composed of syncopated drums, neon melodies, metallic snares, distorted basslines and arsonist vocals spit with a schizo, aggressive attitude at a steady tempo of 140 bpm. Now, let’s move back to the early 2000s, to the three most deprived boroughs in all of England: Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Newham, where the sound was established and given its name.

First things first: grime means dirt. If you were a musician and someone called your music this way, you’d probably react in the same way most DJs, producers and MCs from the scene did: feeling a general sense of disrespect. It took some time, but surprisingly the term stuck. As MC Nasty Jack suggested in a 2006 documentary: “Most grime tunes are made in a grimy council estate.”

Indeed, the whole scene sprouted from council estates—building complexes owned by the local government and rented to low-income residents—, between the late 1990s and the beginning of the new millennium, in an area identified as ‘Inner East London’, historically a complex of blue-collar boroughs, where one could find various heavy industries alongside the docks, which for centuries had been the landing point of many immigrants coming to the city. The clash of these two features made East London an incredibly multicultural working-class community for many years. As you can imagine, smog, pollution, grit and muck of all kinds characterized the environment, and even after the renowned slum clearances during the first half of the twentieth century, the area, entering its post-industrial period, maintained associations with the industries’ sense of debris.

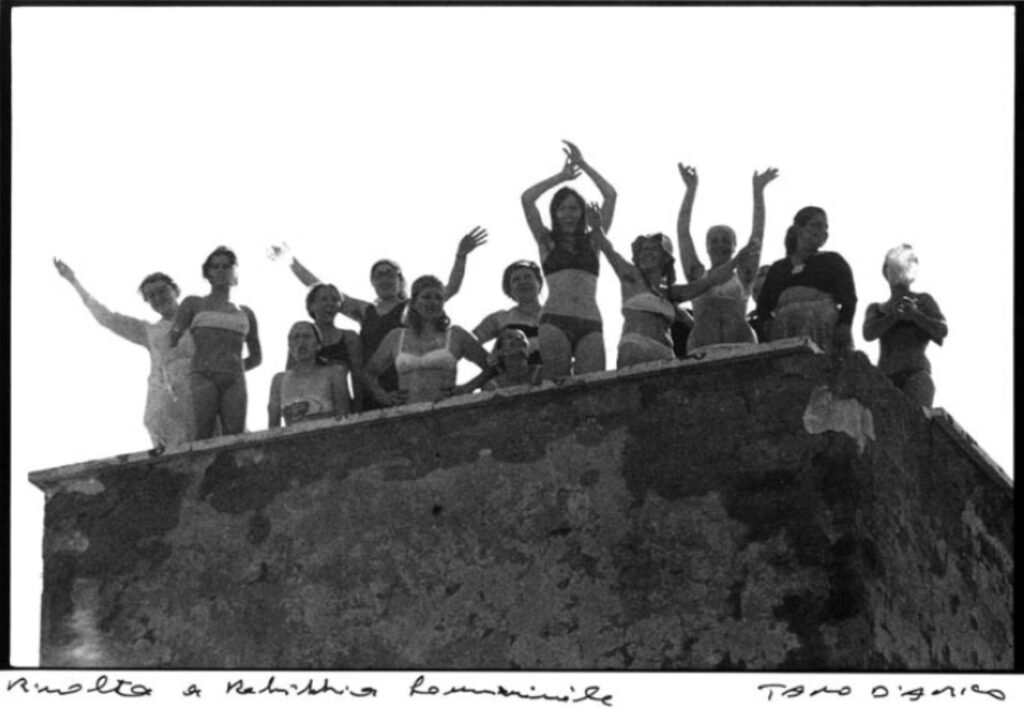

Flash forward to the beginning of the new century: a bunch of teenagers—mostly African or West Indies descendants—are on a council estate rooftop, spitting over unclassifiable instrumentals, gassing each other up and commenting the beats as dirty or gritty, giving their crews names such as ‘N.A.S.T.Y. crew’. Given these premises, it’s not far-fetched to draw a connection between the area’s urban history, the sensations evoked by the environment and the MCs’ lyrical semantics and vocabulary to what eventually became the label-name of the genre.

As London-born music critic Simon Reynolds defines it: “A parochial scene, obsessed with a sense of place.”

Going back to council estates, these 10-storey (and taller) tower blocks and their courtyards often happened to be the first shared playground of this generation of MCs, DJs, and producers. For instance, Dizzee Rascal—the 2003 Mercury Prize awardee and first grime MC to go mainstream—and Tinchy Stryder—Ruff Sqwad crew historical MC—used to live in the Crossways Estate, an infamous 25-storey, three-tower complex located in Bow. Given that in the 1980s 42% of the city council homes were in East London, it’s obvious that these shared urban spaces, together with youth clubs and schools, were the nodes of a community bonding through marginalization in an isolated area, not even served by the tube. As London-born music critic Simon Reynolds defines it: “A parochial scene, obsessed with a sense of place.”

The genre intersects with other phenomena of black diasporic music, through a community heritage that extends far beyond the grime kids’ generation. Many of their parents already knew each other from school and some of them played music together: for instance Wiley’s, Jammer’s and Footsie’s fathers played in the same reggae band. Like a time bomb set to explode, grime was somewhat encoded in the artists’ DNA. Yet, this lineage isn’t only about blood, it’s a musical heritage spreading through the sound systems’ sub-bass frequencies, from its dub and reggae ancestors to grime’s early 1990s relative, jungle music. Grime kids grew up with jungle, and the common ground between these two genres lies more in the environment than the sound itself; an element shared by many music genres: the streets. Quoting jungle’s father figure MC Navigator: “Y’know and its mainly street people that go to jungle. […] At the end of the day it’s all about people that come from an urban background and live in communities. Everyone call them working class or what- ever, but it’s definitely from a street level.”

Same people, same backgrounds, same attitude. It’s not a coincidence that the first appearance of a few of these grime artists spitting bars in a rave or in a pirate radio station was over jungle tracks; artists like the MCs’ favorite grime MC, D Double E, the legendary Wiley and pioneer Riko Dan made their MC breakthroughs over jungle during their teenage years.

Music-wise, the MC component and the adrenaline-filled, fast-paced attitude are what link together jungle and grime. Last but not least, it was pirate radios, their technologies and logistics that connected these two artistic currents.

Defined by Dan Hancox as “the last bastion of truly autonomous, urban working-class self-expression—autonomous in the sense that it is possible to make a living from it, without the approval, or profit extraction, of the whiter, wealthier established British culture industries.” pirate radios were hubs for music that didn’t fit into mainstream channels. Broadcasting sections of rave and urban music especially, pirate radios kept the fire burning around the production of subcultural art forms. All you needed was an FM transmitter, an aerial, a place to set up your studio and that pirate mentality. This meant being a step ahead of authorities, climbing up the sketchiest and highest rooftops to set up your aerial; always being ready to have a plan b to resume broadcasting, because your antenna, well visible by everyone, will eventually be taken down by the Ofcom, the telecommunications police.

Every pirate ship has its captain(s), and the grime vessel’s commanders were Geeneus and Slimzee, who as very young teenagers long before grime even existed, set up Rinse FM in 1994 around the time most pirate radios were getting started. As the story goes, Geeneus and Slimzee met at the jungle pirate station Pressure FM before they eventually got kicked out (apparently a teenage Slimzee was already too good with dubplates, embarrassing the other DJs). Following this, the two decided to set up their own pirate radio station without knowing exactly what they were doing, thus embodying the DIY fuck-all attitude which became the main ethos of grime. Their first broadcast took place in Bow, from the 18-storey-high Ingram House, five minutes from Slimzee’s flat, five minutes from Wiley’s flat and five minutes from Roman Road.

Geeneus and Slimzee, together with the other pirates, created a space of sonic experimentation and social expression for many years to come.

There are several reasons why pirate radios are a phenomenon that is so hyper-locally interesting. First of all, due to technical shortcomings, the average broadcast would only reach a couple of blocks from the antenna. This meant that your audience had to be local and for a station to maintain a sustainable audience, quite a good amount of people had to be living within the broadcast radius. It makes sense to assume that the urbanization of house agglomerates and tower blocks gave the right population density to entertain a community wide enough to be interested in tuning in and keeping the station active. Furthermore, pirate radio stations were also appreciated for their local relevance because they were providing information and advertisements about local community events, businesses, and club nights.

Geeneus and Slimzee, together with the other pirates, created a space of sonic experimentation and social expression for many years to come; a fertile soil where the scene could flourish having the time to find its own identity. They laid down the basis for what would become a collectivist movement, almost exclusively made for an inner circle constrained by the narrow chances and horizons that East London could offer.

As we mentioned earlier, the music of the mid-1990s and beyond was the UK garage, a dance music genre characterised by melodies, sung choruses, champagne poppin’, and being the flyest in the club. But just around the corner of the early 2000s, some MC-centered UKG supergroups began to emerge. Crews where the figure of the gangsta rapper was prominent, such as So Solid Crew—today someone would recognize Asher D, one of the main MCs from So Solid, as Dushane from Top Boy series —, Heartless Crew and Pay As You Go Cartel—the latter formed by Geeneus, Slimzee, DJ Target, Flowdan, Wiley and many more—began to make significant appearances in the charts. It seemed that all those practice hours spent in the Rinse FM studio were the shift toward a more MC-centered music was finally taking shape. Once again, the most intriguing thing is that none of these youths ever meant to go in this direction. Nonetheless, as Geeneus suggests in the following video, it was all meant to be.

Beginning of the new millennium, no one had a name for it but everyone knew what was going on: every Sunday afternoon you could tune into Rinse FM and hear the voice of local heroes through the airwaves, fighting aggressively against each other for their reputation but only clashing with the next MC. Violence was exclusively lyrical whether in radio or in the rave. Listeners might wonder what their faces looked like, and they might have discovered this in the next rave promoted by the very same radio station. This kind of musical violence has often been refused by major labels and criticized by local authorities, but what they failed to understand is that it was just a reflection of the violence present in the streets.

Things were getting a bit darker with the start of the new century. For instance, 2002 saw the highest number of fatal stabbings in the streets over a decade: violence and poverty do not decrease as the pressure increases. All of this was happening in front of Canary Wharf, the business district that, along with other bank citadels, made inner London the richest region in the European Union around the time. Meanwhile, just a couple of miles away, the boroughs of Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Newham—areas associated with the grime scene—were the most deprived of the whole country. Can social and economic disparity get any more extreme?

“At that time, people was upset. People wasn’t feelin’ that soulful. That’s when the sound become known and created. Let’s just take all the melodies off, just get rid of them. Let’s turn the bass up, add more distortion, get the pain out, get the frustration out.”

During an interview after winning the Mercury Prize in 2003 for his first album Boy in Da Corner, looking at Canary Wharf from his bedroom Dizzee commented: “It’s in your face. It takes the piss. There are rich people moving in now, people who work in the City. You can tell they’re not living the same way as us.” If it’s true that music is a reflection of society, it wouldn’t really make sense for the grime kids to produce melodic and joyful songs singing about happiness, or to be boasting about their life at the top of the jetset, poppin’ champagne bottles. As Jammer - grime scene icon and pioneer - suggests in 8 Bar - The Evolution of Grime: “At that time, people was upset. People wasn’t feelin’ that soulful. That’s when the sound become known and created. Let’s just take all the melodies off, just get rid of them. Let’s turn the bass up, add more distortion, get the pain out, get the frustration out.”

The grime community has long faced antagonism from the authorities. From chasing pirates to criticizing and attacking this musical phenomenon as crime related, policies have been of any kind from the control authorities, who at the time were more likely to stop and search black citizens eight times more likely than any other ethnic group. Even grime music itself has been directly targeted: in 2014 Noisey produced a documentary hosted by JME—Skepta’s brother—called The Police vs Grime Music. The documentary investigated Form 696, a Promotion Event Risk assessment which caused the cancellation of many grime shows deemed too dangerous on arbitrary grounds. Active between 2005 and 2017, ‘Form 696’ has been a proper threat to the scene, menacing venues to strip off their licenses, searching artists, recording their personal details and ultimately denying them spaces to perform and sustain their life through music. Someone could draw parallelism to what’s been happening lately in German clubs with artists trying to show support for the Palestinian cause being denied the chance and space to play with last-minute cancelled shows.

Grime’s energy is a product of its environment, fueling the community with its policies and getting backfire from it. It's the voice of the voiceless, the working-class community coming from the ‘council estate culture’. Sometimes even the soundtrack during protests against university tuition raises and public fundings cuts, such as for the grime anthem Pow! by Lethal Bizzle, a track that for a short period was also banned from some clubs’ because they were scared of the hype it created on the dancefloor—grime can be a mad thing.

Today the scene is thriving. The artists have crossed over to the mainstream on their own terms, keeping in touch with their roots. Just like back in the days with DVD series such as Risky Roadz and Lord of the Mics and kids with a handycam independently documenting the scene, in the last few years many editorial and archival instagram pages have popped, putting a bigger spotlight on the scene, thus giving a second life to the genre on a wider scale and creating more room for the scene to thrive. Above them all we perhaps find DaMetalMessiah.

Grime is the sound of collective resilience that buss’ its space back, and as Dan Hancox explains: “Buss meaning to fire a gunshot, bust a move, or strike out, express yourself – find space and freedom. Grime in its first flash of youth was thrilling because it was claustrophobic, a hectic cacophony of beats and synth stabs, channeling the high-rise tension of tower blocks, the limited horizons and possibilities. But just like real claustrophobia, it demands freedom—and space.”